Archive for the ‘Museums’ Category

Florence – the Grand Tour, November 2025

It is clearly about time. Florence. The Renaissance. History. So, we did it. Monday by train from Munich. Saturday back. We stayed at the Novotel near the airport (see below).

Day 1 – wandering around. Florence is one of those places that if you do wander around you are likely to see everything that is free. Including the reproduction of Michelangelo’s David, left. The original is in the Glleria Dell’Accademia di Firenze and has an entry fee.

Day 2 – the Uffizi gallery. We must go and see Venus at the very least. And the Botticelli pictures more generally. It is a strange gallery. Note that it has ultra-strict security since the bomb attack in 1993. But basically, it is a rectangular building with small galleries off a corridor (right). The building itself dates from 1581. The upper floor is the gallery that comprises a corridor adorned with sculptures and frescoes. It is actually quite difficult to see all of this art without laying on one’s back. And so one wanders around taking in what the senses can appropriate.

There are unexpected surprises such as a smattering of Mannerisms, for example, Portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées with one of her sisters, Bathing. This image is mischievous but also representative of a mannerist depiction of feminine beauty and fertility. Just oddly included in the collection.

Florence is not complete without the arrival of Caravaggio and his followers with some gruesome depiction of decapitation or similar. The Uffizi does not disappoint offering a themed gallery with my favourite being the Judith Beheading Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi. I suppose these pictures very much reflect Renaissance Florence, certainly somewhere violent enough for one’s head to be removed from one’s shoulders without too much effort. Though interestingly conducted by women.

Is the Uffizi a great gallery? It does have a remarkable collection. But I have to admit, I got a bit bored. It would benefit from an edit (I know that it is carefully curated, but…) largely because of the period. There is a lot of replication. Arguably the visitor could do their own edit ahead of time. Though let me put it this way, it is not the Louvre.

Day 3 – we must go to the cathedral (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower) and climb to the top of the famous and unique dome. There are three compelling reasons to do this. First, the roof frescoes cannot be appreciated fully from the ground. Part of the way up the climb to the summit, one gets to walk around the base of the inside of the dome and almost touch them (see gallery below).

Second, your get to walk in between the two structures that make up the dome. The amazing thing about the dome is that prior to its construction there was little understanding about how to make such a structure. The architect Filippo Brunelleschi, such that he was, sort of made it up. He created a secret formula that involves a dome inside a dome. And the staircase to the top walks you between the two structures (left). The precise physics are explained and illustrated with models in the cathedral museum which is also well worth a visit (see gallery below).

Third, on a clear day, there is a spectacular view from the top. I have to say, I was pleased to be able to see the railway station (right). Of all landmarks in a city, the railway station is the one that most captures modernity. In this case, location, bearing in mind the historical roots of the city predating the arrival of the railway, to have it so central speaks loudly. Florence is a city that was embracing and inventing technologies as much as it was doing art (see Galileo Museum below).

Book in advance. Space at the top is limited and it is popular, even in November.

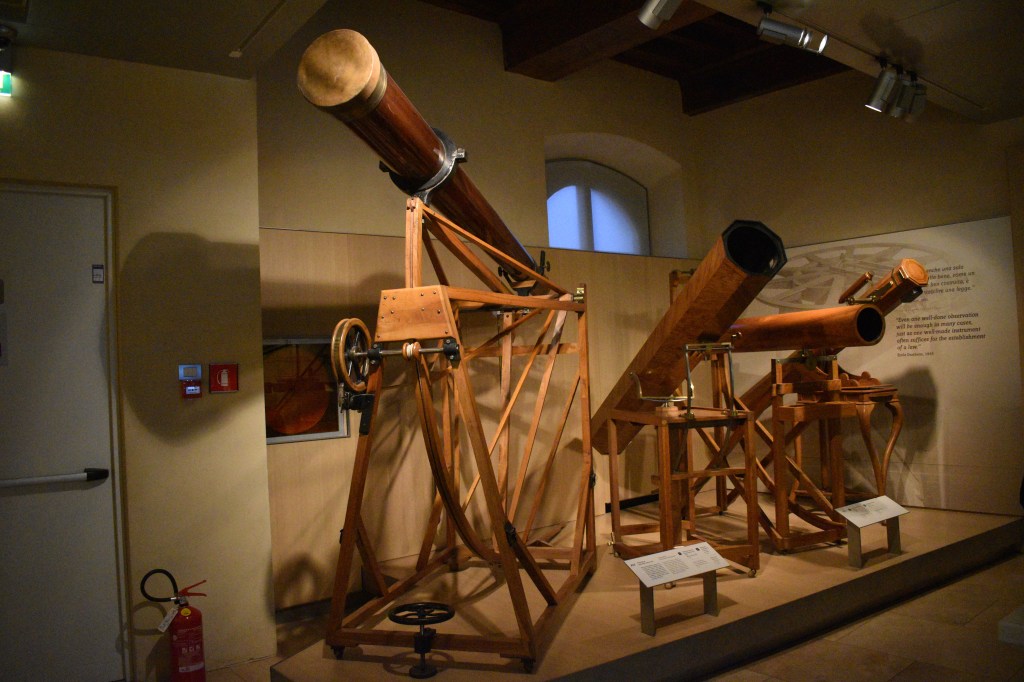

Day 4 – the Galileo Museum.

I have to say, that if visitors to Florence do not patronise this museum, then they are missing out. Plus, it is relatively quiet (though, clearly, it should be really busy). This is a museum packed with analogue scientific instrumentation as art. Functional, yes, but that was never enough for the pioneers – professional and amateur – it had to be beautifully made, whether it be a chemistry cabinet (left) or a timepiece. This museum is packed with artefacts that came out of the Renaissance and beyond that eventually led to humanity’s greatest discoveries facilitating developments that laid the foundation for 20th Century civilisation.

Getting around

It should be easier than it is. Some pitfalls. Buses are unreliable. And in the evening, less frequent. If a bus does not turn up in the evening, it can be a long and uncertain wait for the next one not to turn up. The two tramlines are more reliable, but they too fail. If you have a train or plane to catch, be ready with a taxi number. Probably better to stay centrally (for the train) or at the airport (if flying). Though check that the hotel is in fact at the airport and not just close to it.

Here are some more pictures.

Dome Frescoes

Dome Museum

Galileo Museum

David Hockney, Paris, August 2025

Eurostar from London, dinner, nearby hotel, sleep and then work out how to get to the Fondation Louis Vuitton building that, due to my lack of preparation, turns out to be a Frank Gehry building (left). It sits in a bizarre park that is home to a retro amusement park, amongst other things. Over breakfast we decided to walk – Google maps advised nearly 2 hours, but such is Paris, walking is a delight. By chance we ended up meeting up with an electric bus shuttle from Arc de Triumph to the building – further than we thought. Anyway, the marketing for the exhibition is here.

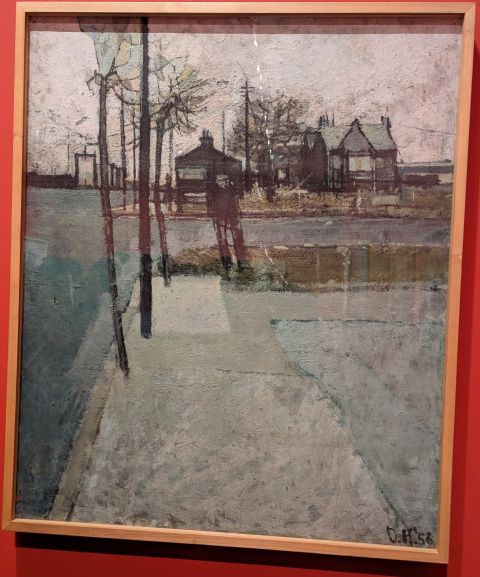

Once into the building we did as we were told and started in the first gallery. It was an exhibition that was organised chronologically by date. So Hockney’s earliest works can be found in that gallery, including the portrait of his father, life in what is now Greater Manchester (right) and series of abstract paintings exploring his early understanding of his sexuality. Then in 1964 he heads off to California. This period delivered some of his most famous images, for example, the Bigger Splash and a series of other poolside paintings that are now beyond my price bracket. But I have to say, I found this rather boring, egotistical, even narcissistic.

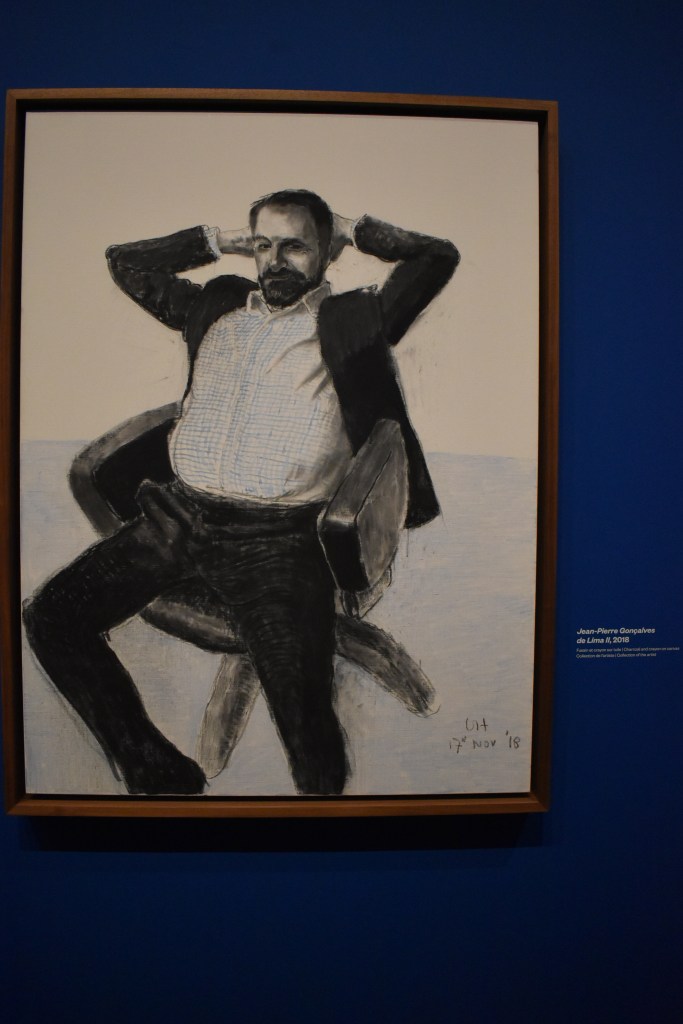

Portraits

I like to think that artists have something to say (about the world) beyond themselves. Maybe the next gallery of portraits might reveal something, after all, the sitters were others, often pairs of others. There were lots of admirers of these portraits, but I felt that most lacked emotion. In fact, the only picture (actually a set of four) that showed emotion were a man towards his dog. All others seemed inert. I found one image that summed up this whole gallery (below right).

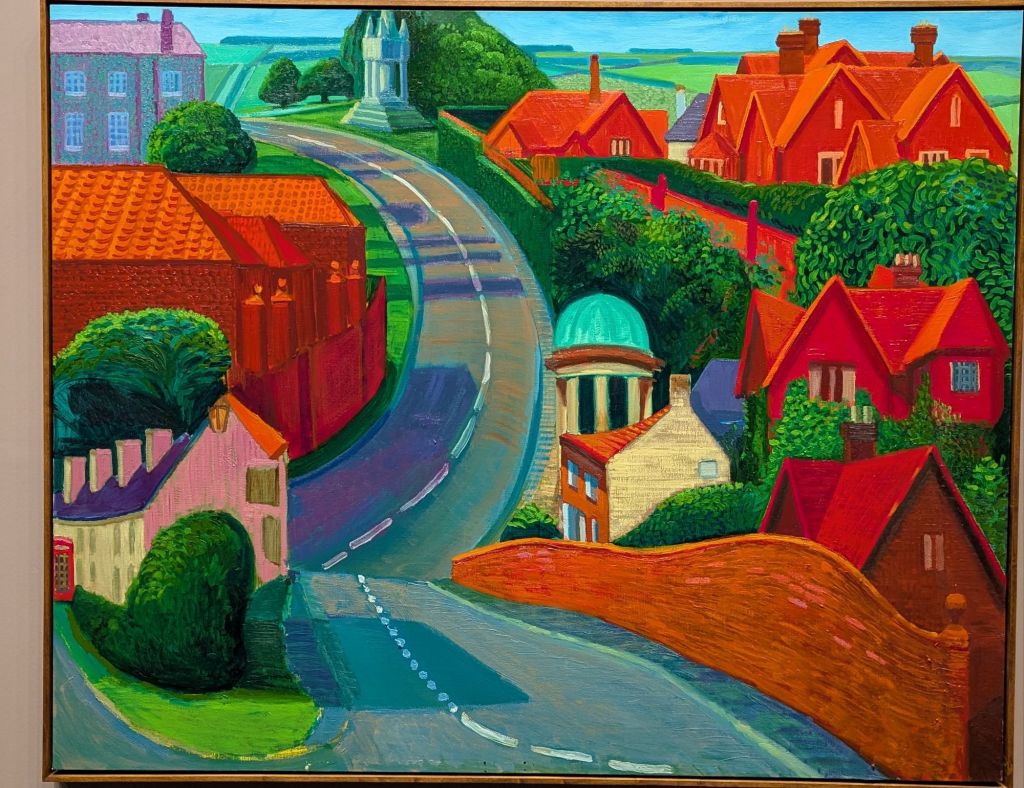

East Yorkshire

Onwards – Hockney came back to the UK and moved into his deceased grandmother’s house in Bridlington, Yorkshire. In this period he produced a significant number of landscapes depicting changing seasons; for example, a spot on a farm track. Man, easel, paints, brushes. Some of the pictures are huge, made up of 40 or so panels that oddly do not quite match or line up with one another. And they all seem to be without people or, indeed, animals. I can cope without people in the countryside. But not an absence of animals.

That was enough, time for coffee. We left the building in order to find refreshments – the gallery itself has an expensive restaurant but no coffee shop from what we could see. The park has a number of delightful outlets, so no problem.

The full artist

We were back within the hour to a gallery on the second floor which, frankly, we should have started in. This gallery showed what a consummate artist Hockney is and what he could have been had he wanted to be – but that is me being arrogant. I say this because Hockney himself writes on the entry panels that we might think that he has limited styles on which he can draw for his “periods” – all long-lived artists have those, I have come to realise. In this gallery were examples of Hockney aping the styles of other famous artists. There is always a nod to van Gogh, but we did not realise he was a fine cubist artist in the style of Picasso. I particularly enjoyed his take on Hogarth and the illusions generated in his picture, Kerby (After Hogarth) Useful Knowledge, 1975 (above left).

Then on to Munch and Blake (After Blake: Less is Known than People Think, 2023, left). This is the only image that alludes in any way to the welfare of the natural environment (the landscape gallery does not address any of our environmental challenges, indeed reproduces them with straightforward depictions of modern lowland farming). Blake’s painting was a representation of Dante’s Divine Comedy which, admittedly, I have never read. But here we have a holistic view of our human world – a dependence on the natural environment, the awe and fear of the galaxy and universe beyond, human history and a vulnerability (unclothed women holding up the globe) to the planetary system more generally. As we know, we have moved from the Holocene to the Anthropocene – our fate is in our hands, and we ignore the signals at our peril (increasingly decreasing temporality).

Theatre set drawing

And then there is the theatre work. Hockney was a great fan of opera and throughout his career he has been painting backdrops for some of the great opera houses worldwide. For this exhibition his work is immersive. One enters a large gallery to observe the paintings projected onto walls, with some being animated and involving motion. They are terrific. Another important aspect is Hockney’s experimentation. For example, he has created intriguing electronic pictures that track his method for drawing and painting, particularly landscapes. All credit to him for this. I spent quite a bit of time over these images.

Photo drawing

More recently Hockney has explored “photo drawing” (right – one of a series depicting the same “event from different angles). Equally in this almost recursiveness is his image of himself looking at his own pictures with subtle references to his own brilliance, such as the edition of “die Welt” underneath the small table (below left). And these, for me, sum it all up. Whilst I concede that Hockney is a versatile artist, able to work in most styles and genres and has a body of work that can fill the Fondation Louis Vuitton building in Paris. He is also just a shade too narcissistic for me really to embrace.

Exhibition ran from 9 April – 1 September 2025

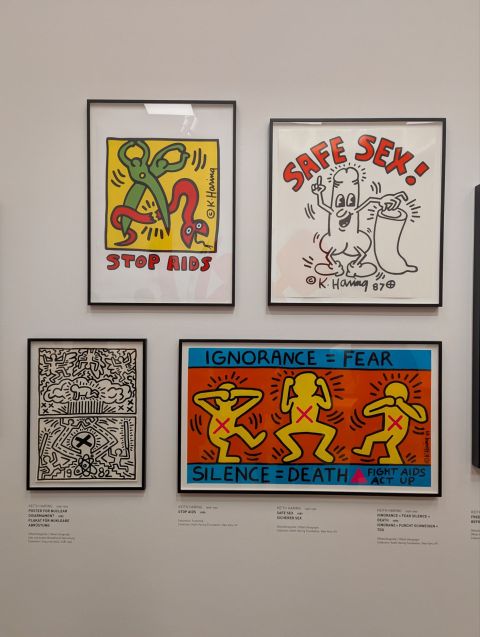

Warhol and Haring together at the Brandhorst Museum, Munich, December 2024

I had not realised it earlier – or not paid attention – that Keith Haring and Andy Warhol were artistic compatriots. There is a generational difference, for sure. Stylistically, too. But this superbly well curated exhibition (on until the end of January 2025) brings the two artists together – their lives, loves and work.

Haring is this curious subway graffiti artist (Haring would prefer me to drop the graffiti adjective) who became the artist he wanted to be, commercially and critically successful. In 1986 he opened Pop Shop in New York (292 Lafayette Street) to sell his designs on all sorts of artefacts – from textiles to skateboards (left).

For both of these artists I found plenty of contradictions. Haring, particularly so. Whilst both were so-called pop artists, that did not mean they were not looking to be commercially successful. Neither were bohemian in that sense. Whilst Warhol famously bought a factory in which to live, work and socialise, that came at a (financial) price. Haring wanted his work to be as accessible to as many people as possible which explains to some extent the subway art. He was often arrested for this, but seemingly his whiteness protected him from serious prosecution. Many of the works were removed (stolen evening – though whether graffiti can be stolen, I am not sure) and sold at auction as he became increasingly marketable. He moved on to free work for charities and hospitals where, presumably, his work would be a little more protected. His work was also printed onto dresses worn by Grace Jones and Madonna both of whom he met through Warhol.

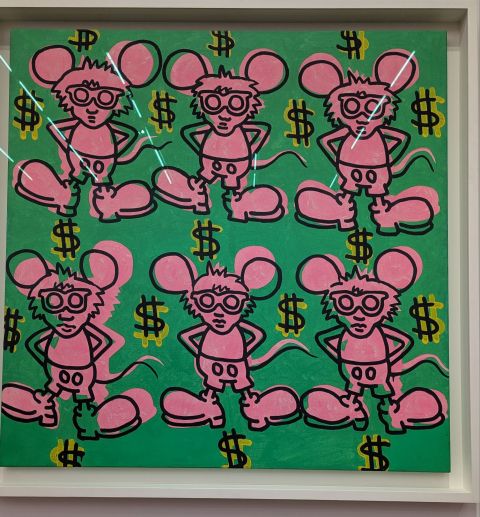

But the affection the two men had for one another was the focus of my approach to the exhibition. I am not sure for myself if a friend caricatured me as Mikey Mouse (right) that I would be too chuffed. But Warhol was delighted with Haring’s effort which captured the essence of the man (for sure it is Warhol), one of his styles (repetition) and critique (Disney and dollars).

Warhol died in 1987 after some disastrous surgery. Haring was devastated and did what most artists would do, remember them through art whether it be visual, aural, written, whatever. Haring went for a curious depiction that takes some explanation. Warhol is naked. (Warhol had taken naked photographs of Haring in the past.) Warhol is sucking a banana which was a common Warhol motif. He is holding an apple that is somewhat sorf and juicy. This perhaps has a number of meanings – by this time Haring himself was ill with Aids and had a prescribed diet which included a lot of fruit. Equally, it could mean something else entirely.

Both Haring and Wahol were social activists as well. Haring’s social commentary ranged from Aids awareness to anti-apartheid statements (right). There is also an endorsement of the German Green Party.

In the true spirit of Haring’s accessibility, we visited on a Sunday when the entry fee is just 1 Euro. We had dinner in a nearby Vietnamese diner. The front-of-house was dominated by a woman who had an amazing ability to take multiple orders without writing anything down and then remembering who ordered what. Very Warhol.

Gran Canaria: museums, galleries and colonialism

Museums and galleries

Las Palmas – the capital of Gran Canaria – is home to at least four museums, three of which we visited.

Naturally there is a Columbus Museum (Casa-Museo de Colón – https://www.casadecolon.com/) that chronicles the significance of the islands for Columbus’s so-called discoveries. What we learned from the museum was how strategic the islands were for transatlantic crossings, particularly to the Caribbean. Columbus made four such crossings as captain and for each, the Canary Islands provided resources – food, water and labour. For example, for his first tour he needed, essentially, to refit his ships and fix a rudder.

The museum basically presents maps and artefacts in a reproduction of ship environments; for example, the Captain’s quarters showing a bed, desk (right). There is lots to learn about cartography – the evolution of maps is part of the story, of course. Visitors trace through the centuries how humanity moved from a flat earth to a globe and eventually got the shape of the continents right. I suppose cartography is the discovery that we can celebrate if not the conquering aspect of the voyages.

I give them credit for being focused and not getting distracted – Columbus is a big story. It is a lovely small but informative museum close to the cathedral in the historic centre of the city.

The top floor of the museum is an art gallery with time-limited exhibitions. At the time of our visit (29 November 2024) was a celebration of the work of a Canarian artist, Juan de Miranda. There is, as one might expect for a painter of his era, a lot of religion and aristocracy. But also some quirks. For example, I was intrigued by the portrait of St Lucia dated from around 1785. St Lucia is often depicted with eyes on plate. The meaning is not entirely clear but it is thought to reflect her lack of desire to marry. To be blind and eyeless – or to have one’s eyes literally disembodied – may well help her to avoid what she did not want!

CAAM – Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno

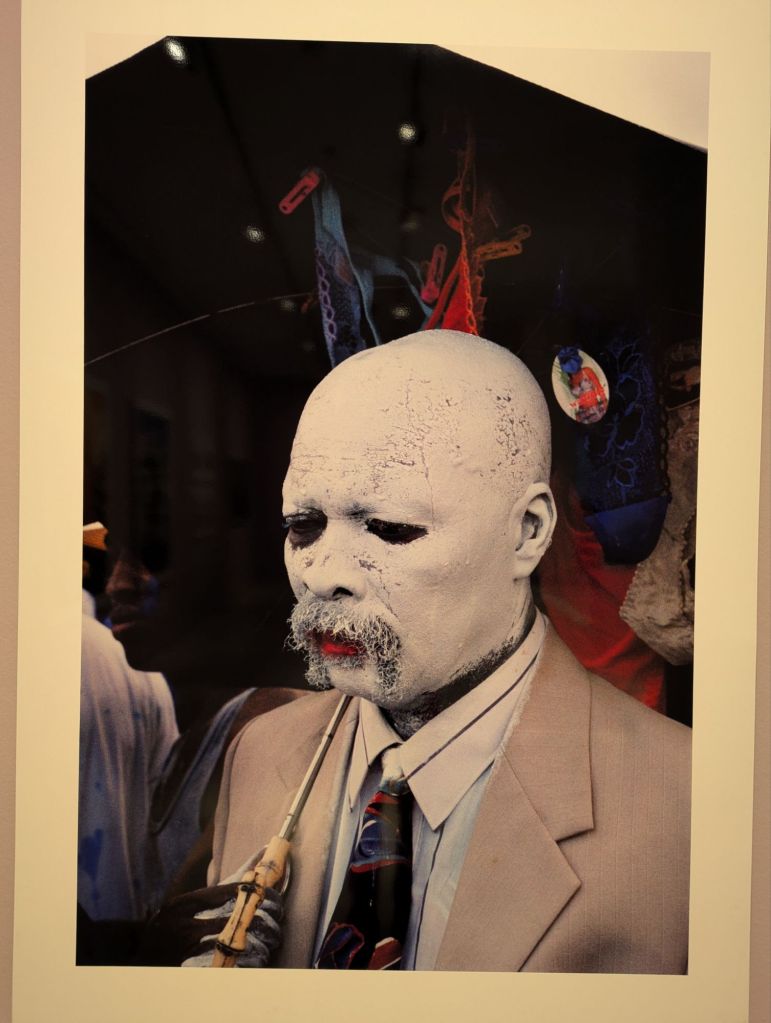

As one might expect, this is gallery of modern art (free entry). Over three floors there are three exhibitions dedicated to particular artists and themes. On our visit (4 December 2024) the artists were: British artist, Zak Ové; Canarian artist, Juan Hidalgo Codorniú and Teresa Arozena. Arozona’s work featured large prints of photographs showing the impact of tourism on the natural environment of the islands of the archipelagos (largely negative). Whilst they are recognisable for anyone who opens their eyes as they wander around the tourist spots (and possibly beyond), they are not particularly standout or framed in an interesting way. For example, shots of the dunes of Maspalomas fail to capture their scale (always difficult with photographs) and show engagingly the threat posed to it. I sense that we as tourists may have some better shots to take home with us.

Juan Hidalgo Codorniú had a lot to say about himself. A long career (he died in 2018) as a conceptual artist presented some interesting artefacts. Like for all conceptual artists, there are good, interesting and not-so-interesting pieces. Bizarrely in one of the galleries is a large area of simple pornography, and another a series of pictures of the artist with nude models. Let me put it this way, they are of their time (the latter the 70s), but unworthy of the exhibition more generally. One piece stood out, though. The depiction of the Earth in a condom (right) resonated. Though I suspect his meaning was different to mine – rather more sexual. It gave me a sense of the earth being emasculated/suffocated, particularly by men. But all we need is a little tear!

Finally, Zak Ové, whose collection here was streets ahead and eclectic. Ové’s father was also an artist and this work seemed like an extension across generations. Both men had a deep commitment to black rights. Seemingly the family lived adjacent to Michael X (aka Michael de Freitas) – there are some atmospheric photographs of him – one particular in Paddington Station, London. (He was eventually convicted of murder and executed in Port of Spain in 1975.) Images of the Notting Hill Carnival in the 60s also feature. Striking images include Evil is White (left) – though for me it could also include the adjective, male.

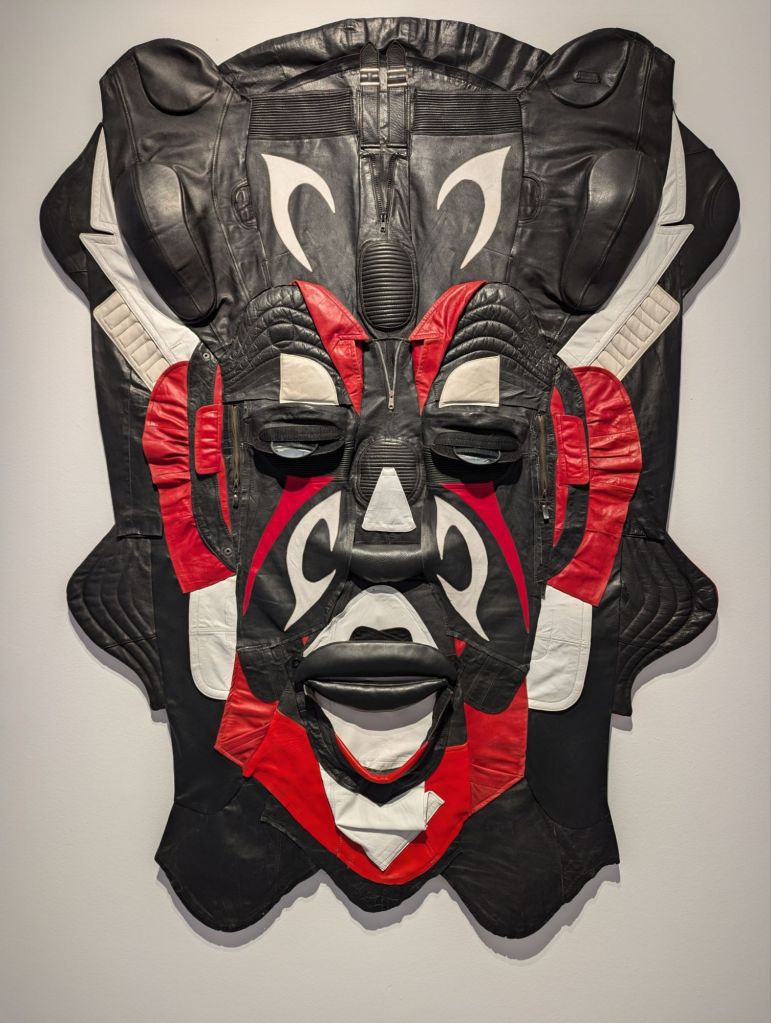

Ové is also a big user of re-used materials. One gallery demonstrates the fun and creativity associated with his approach. For example, for Fish (2009) he used brass instruments, rubber gloves and dolls. There is a series of masks made from old leather jackets dating form a 2024 collection.

Ultimately, this is a fascinating exhibition in an unlikely location. All the better for it.

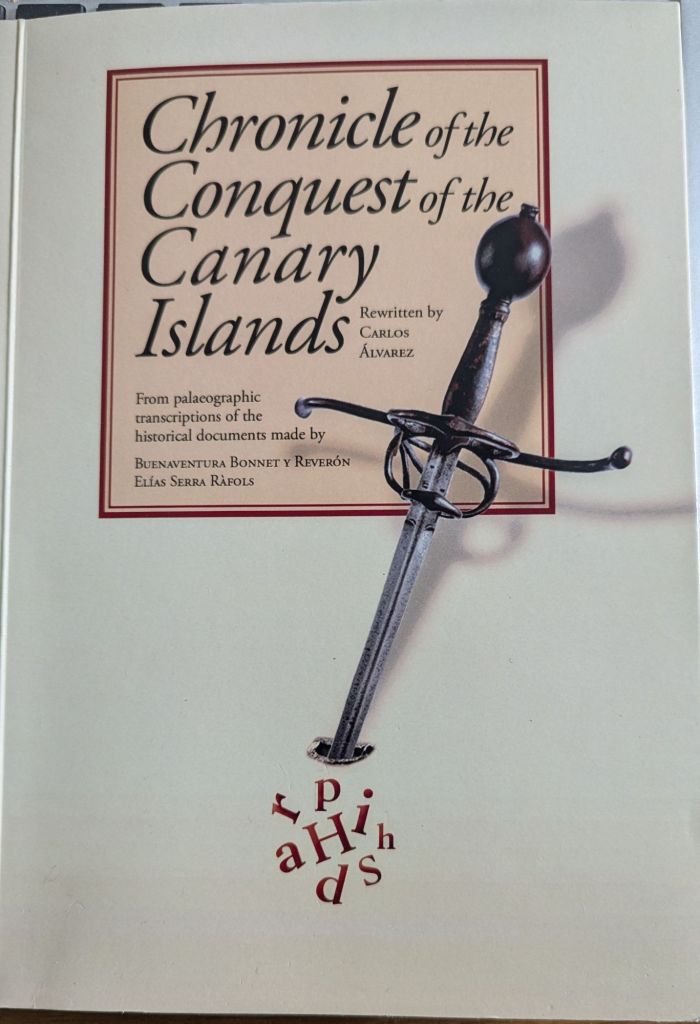

Museo Canario

This museum is charming. It is made up of a private collection that was donated along with the building that charts the pre-history of the indigenous people of the island up to the point they were conquered by the Spanish. So it does not deal with the conquest. I bought a book to take up that story – it is complex, see later.

Charm comes in many forms – the building (left, the gift shop is housed in the collector’s library); the collection is disproportionately comprised of lots of bones and skulls; the staff (guaranteed not to leave without having visited the gift shop and bought something) and a curious but welcome adoption of technology (QR codes enable visitors to have an audio guide for each gallery in a selection of languages).

The story is one of arrival (by boat with a few animals and seeds); shelter (in caves and huts); clothing (tanning animal skins and weaving); food (agriculture, preparation/grinding of grains particularly barley); pottery (technology and types) and death (causes and funerals). There are representations of life dotted around the galleries. For example, pottery making (right).

The are other museums and galleries on the island. In Las Palmas, for example, there is El Museo Néstor, dedicated the work of the Gran Canarian artist Néstor Martín-Fernández de la Torre. Moreover, Gran Canaria is more than Las Palmas. There are important other towns in the north of the island such as Galdar.

Colonialism

The colonial history of the islands seems to be something few museums want to address. The conquest of of the islands is not told in any depth. I had to do my own research and, so far, have relied on a single source, Carlos Alvarez’s book, Chronicle of the Conquest of the Canary Islands (left).

Alverez notes that there are a number of different accounts of this period (17th Century), none of which, of course, take account of the indigenous populations’ experiences. Alvarez has done a lot heavy lifting for us in checking the facts; for example, when false dates are presented, he make it explicit to us that it is false and why (if possible). In reading the book I conclude a number of things.

- The islands were not homogenous – geology, culture, natural resources. I sense this is still the case today.

- Colonialisation requires the cooperation of an indigenous population – on Lanzarote, the population surrendered rather quickly realising that they could not defeat the invaders. They agreed to be converted to Christianity as confirmation of their surrender.

- Of all of the islands, Gran Canaria was the most difficult to conquer (eventually in 1478). The final conquest was brutal – but conquistadors suffered high losses until Captain Don Juan Rejón arrived armed and prepared for his success attempt at conquest.

- The islands became property of the Spanish nobility (though the Portuguese had a go at wresting control by miliary force). They were traded between Spanish nobles. The owners and nobles were paranoid (fearful of losing their claims) and vindictive. This actually led to the “accidental” death of Captain Rejón an (unwelcome) unscheduled landing on La Gomera en route to La Palma (yet to be conquered). Consequently, the story of the conquest is told in the voice of the nobles – and their squabbles – rather than the voices of the indigenous people.

Summer 2022: the €9 ticket holiday – 2

Art

Holidays often feature art – why would they not? In this journey we’ve been to Berlin, Elblᶏg and Dresden. The latter two are provincial cities with their own take on what should be shown and what not. And how.

Elblᶏg surprised me. The art is everywhere in the public realm. Seemingly in 1965 a number of artists were commissioned to make art and place it just about everywhere in the city. Examples of the work are below, but what it does to a place is interesting. In some cities the art would be defaced, damaged or vandalised. I saw none of this. 1965 – that’s 57 years! I assume that the art reflects the town and its people. Most of the artwork is made of steel, yet compelling. Maybe no one notices it, but it is there.

In Dresden, art has a very different role. Dresden celebrates its kings or “electors” The Residenz – effectively the palace of the elector August the Strong (apocryphally he can snap a horse shoe by his brute strength). He was strong, but probably not in this sense. His art collection – or treasures – illustrate just what constituted his ego. There is no question that most of the objects in the galleries are exquisite. I simply cannot imagine how most of them were decorated. Some of them were linked to what was probably 17th Century high technology such as clocks. The example on the left is a roll-ball clock. The ball is rock crystal and it rolls down the tower. It takes exactly one minute. Inside, seemingly, another ball is raised “emporgehoben” (whatever that is supposed to mean in reality) which moves on the minute hand. Saturn then strikes a bell, and twice a day the musicians raised their wind instruments and an organ played a melody. It is an extraordinary piece; but somehow I prefer time keeping to be a little simpler, at least in its reporting.

The jewels are one thing, the ivory is quite another. I have to say I’ve never seen so much carved ivory in one place. It is quite sickening. The carving is amazing, however. Take this frigate (right). I do not know how many elephants died for this piece, but everything apart from one feature is obscene. It dates from 1620 and bears the signature of Jacob Zeller. Of course the frigate is supported by the carved figure of Neptune. The sails are not ivory, nor the strings. But there 50 or so small human figures climbing those ropes. They are extraordinary.

There is an ivory clock to rival the jewelled example above. But quite the most sickening is to carve an elephant from ivory (left). There’s a receipt for its purchase in 1731. It is actually four perfume bottles hidden the castle turrets. What gets me particularly is the failure of the gallery to say anything about the exploitation of nature. These are simply curated as exquisite objects of great value.

It was not only elephants from the natural world that were exploited. Here is something I absolutely did not know, coral was a material for artists and treasures in this period. The bizarre figure on the right is seemingly a drinking vessel in the shape of the nymph Daphne who metamorphosised into a tree (coral) to escape Apollo’s “harassment”. It is not just one piece, there’s lots of it in this gallery. Not a word about how the coral was gathered and where from.

But there’s more. There are some deeply troubling figures of black people. I am not going to upload the photos of a sedan chair occupied by an ivory Venus and carried by “Hottentots”. Venus is attributed to court sculptor Balthasar Permoser (1738 or so) and the figures to court jeweller Gottfried Döring.

I left this gallery feeling troubled and dissatisfied with the curation. They must do better.

The Albertinum is another gallery in the historic centre of Dresden. There is some interesting stuff here. Sculpture is not usually my thing, but it has a number of examples of art that was deemed by the Nazis as “degenerate”. For example, Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s “Kneeling Woman” (1911, left) which is quite extraordinary, but obviously too extraordinary for the Nazis. Then oddly there is a piece by Barbara Hepworth, Ascending form Gloria, 1958). Odder still is a decorated wooden crate ascribed to Jean-Michel Basquiat (I am probably wrongly describing it). There are a couple of contrasting pieces by Tony Cragg – a wooden abstract sculpture and a cube made up of compressed rectangular objects ranging from lever-arch files to old VHS video players.

The upper floors are full of fine art. Again, keeping to the theme of degeneracy, climate and perhaps art that captures some of the potential consequences of unchecked warming, I start with Ernst Ludwig Kirschner’s Street Scene with Hairdresser Salon (Straβenbild vor dem Friseurladen, 1926). Kirschner was part of a group of artists known as the Brücke Group. Like many art movements the members were all against “old establishment forces” and following artistic rules. The bright colouring is an example. So shocking were the paintings that they could not be purchased by the City. Eventually, they became accepted and acceptable, only to find them labelled as degenerate in 1937.

What was not degenerate was Hermann Carmiencke’s Holsteiner Mühe (1836, Holstein Mill). I choose this because water was a natural source of sustainable motive power. The steam engine was arguably introduced to break the collective power of labour and because the water resource ultimately could not be shared by the direct owners of capital.

Finally from the Albertinum I selected Wilhelm Lachnit’s Der Tod von Dresden (1945, The Death of Dresden). It is, of course, a reflection on the human suffering arising from the second-world war. The climate crisis will bring its own deprivations and a fight for resources. We will see these times again, I fear.

A quick word on Dresden. The historic centre was essentially rebuilt from 1985. Many of the historic buildings were left as shells and rebuilt using plans and authentic materials. It was an exceptional achievement and good on the eye; the Semper Opera House, for example (above left). But this is not a city preparing for rising temperatures. Whilst there are green spaces, this central area is totally devoid of natural shade. The new centre around the railway station is largely concrete-based retail. Could be anywhere.

Meanwhile in Berlin, we visited the Nationalgalerie. I was taken by the work of Adolph Menzel. He obviously earned his money painting portraits of rich men, but he also had much to say about contemporary issues of the time – the mid 19th century. He is, by definition, a contemporary of Turner. And Menzel’s picture Die Berlin-Potsdamer Eisenbahn (1847) has some similarity to Turner’s Rain Steam and Speed which dates from 1844.

Menzel also painted a number of factory scenes – Flax Spinners, dangerous women’s work. The only safety equipment is clogs on their feet.

Contrast this image with that of his painting Flötenkonzert Friedrichs des Groβen in Sanssouci (1850-52). This depicts Frederick the Great playing the flute with a small ensemble and aristocratic audience. It takes place in a grand setting. At night with candles galore as illumination (expensive, if nothing else). It is incongruous. Those flax spinners will not be consuming high art at this hour, for sure.

The industrial revolution and the ruling (plutocratic) elite play their distinct roles in the journey to the current climate crisis. Images of trees being cut down are visual reminders of how the natural environment is the source of all exploitable resources. Constant Troyon’s painting Holzfäller (1865, Woodcutter) is a great illustration of this. Though I am sure this is not the actual meaning of the painting. Trees were, of course, felled well before the arrival of the industrial revolution for shelter, housing and agriculture. What is significant is how the deployment of technology turned it into a truly industrial process. Watch how trees are harvested in modern times as though they are bowling pins, to understand how the pace of destruction has increased.

There is one other theme here, to share. And that is “otherness”. Mihály Munkácsy’s 1873 painting Zigeunerlager (Gypsy Camp, right) expresses it well and nicely contrasts with Menzel’s Woodcutter (I note and am aware that both Zigeuner and Gypsy are pejorative terms. The Nazis, we remember, committed genocide against this group. Hence the word Zigeunerlager is particularly troubling. The correct term is Der Roma). That very same landscape lost to the axe is potentially a place of refuge for nomadic people. These are people who are seen as being rootless (and stateless), where in actual fact probably the opposite is true.

What to do with an old tram shed in Berlin

The new academic year starts in a few days’ time. The time immediately before is conference season for us journeyman academics. I’ve been to two.

One way of judging (or being judged, if one is an organiser) is the mid-conference dinner. Last week, at a conference in London, this was held on a cruiser on the Thames. It cost extra. A nice spectacle, particularly those unfamiliar to London. A great opportunity for photographs (left), especially in balmy weather.

One way of judging (or being judged, if one is an organiser) is the mid-conference dinner. Last week, at a conference in London, this was held on a cruiser on the Thames. It cost extra. A nice spectacle, particularly those unfamiliar to London. A great opportunity for photographs (left), especially in balmy weather.

The food was a bit…

I’m now in Berlin, one of my favourite European cities. This is an academic corporate-sponsored conference. The venue for the dinner was inspired. The entrance to the Classic Remise on Wiebestrasse in the North West of the city is modest. Once inside, it seems like a museum, but in actual fact it is one huge second-hand car sales showroom. Everything is for sale, at a price. The VW camper (right) is so valuable, that one has to request the price. It has been beautifully restored.

the dinner was inspired. The entrance to the Classic Remise on Wiebestrasse in the North West of the city is modest. Once inside, it seems like a museum, but in actual fact it is one huge second-hand car sales showroom. Everything is for sale, at a price. The VW camper (right) is so valuable, that one has to request the price. It has been beautifully restored.

Clearly, these being vintage cars, supply is limited. But it does seem that, within reason, one could buy – and presumably sell – anything here. Tucked away on a platform, I saw a Ford Capri MkI. Naturally, there are many BMWs, Porsches and Mercedes of various vintages. But American cars also feature. There were three Ford Mustangs as well as a lumping 1930s Lincoln. Magnificent and obscene in equal measure. The resource that went into building it, to meet with GM’s ‘cars as disposable fashion accessories’ industrial design and business approach, must have been huge.

Now I am a white van man (there were a few vintage Citroen vans in various stages of refurbishment), hence prioritising an image of a VW camper over a Porsche. More interesting, however, was the building. I would not have guessed its origin without a trip to the toilet. And, there, on the wall, were some pictures of the very same building with trams peeking out like horses in a stable (left). When first built in 1901, it was Europe’s largest tram shed ‘Wiebehallen’. It is the work of the Berlin architect, Joseph Fischer Dick, who seemingly specialised in these structures. The current owners have been faithful

Now I am a white van man (there were a few vintage Citroen vans in various stages of refurbishment), hence prioritising an image of a VW camper over a Porsche. More interesting, however, was the building. I would not have guessed its origin without a trip to the toilet. And, there, on the wall, were some pictures of the very same building with trams peeking out like horses in a stable (left). When first built in 1901, it was Europe’s largest tram shed ‘Wiebehallen’. It is the work of the Berlin architect, Joseph Fischer Dick, who seemingly specialised in these structures. The current owners have been faithful to the building. Whilst the tracks are no longer there, the entrance arches are all numbered. The roof glass and steel frame remain. As do the authentic lights (albeit with modern bulbs).

to the building. Whilst the tracks are no longer there, the entrance arches are all numbered. The roof glass and steel frame remain. As do the authentic lights (albeit with modern bulbs).

The food was also good.

Rotterdam, museums

Rotterdam, at first sight, seems not to have any recognisable iconic buildings that so differentiate other European cities. However, Rotterdam makes up for this in museums and food. Spoilt for choice, just wandering around ensures that one encounters objects – cranes, boats, steam engines – from the maritime museum (left) with bi-lingual history plates.

Rotterdam, at first sight, seems not to have any recognisable iconic buildings that so differentiate other European cities. However, Rotterdam makes up for this in museums and food. Spoilt for choice, just wandering around ensures that one encounters objects – cranes, boats, steam engines – from the maritime museum (left) with bi-lingual history plates.

The Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen is the City’s primary art gallery, home to an eclectic mix ![]() of pictures, sculpture and furniture. Some of the pictures are very special. Paintings by René Magritte always seem like old friends, unless one has not met them before as in the case of La jeunesse illustree,1937 (right) with its path occupied by some familiar – and not so familiar – Magrittian objects against a blue sky and deep green grass. There are examples from a number of notable surrealists including Man Ray and Salvador Dali. Cubism in the guise of Picasso is also well represented.

of pictures, sculpture and furniture. Some of the pictures are very special. Paintings by René Magritte always seem like old friends, unless one has not met them before as in the case of La jeunesse illustree,1937 (right) with its path occupied by some familiar – and not so familiar – Magrittian objects against a blue sky and deep green grass. There are examples from a number of notable surrealists including Man Ray and Salvador Dali. Cubism in the guise of Picasso is also well represented.

There is work by Van Gogh; for example, Cineraria’s from 1885. Still life is celebrated more widely, with Claude Monet’s Poppies in a Vase from 1883 (both left).

There is work by Van Gogh; for example, Cineraria’s from 1885. Still life is celebrated more widely, with Claude Monet’s Poppies in a Vase from 1883 (both left).

The curators of this museum have much humour integrated into the plates. For example, Jan Adam Kruseman’s Damesportret from 1829 (pictured right) is, according to the curators, apparently a lesson in timelessness. The unnamed sitter is dressed in all her finery, which, at the time, may have been the height of fashion, but now looks a little overdone and reflects badly on the judgement of the painter rather than the sitter. Lovely smile, though.

plates. For example, Jan Adam Kruseman’s Damesportret from 1829 (pictured right) is, according to the curators, apparently a lesson in timelessness. The unnamed sitter is dressed in all her finery, which, at the time, may have been the height of fashion, but now looks a little overdone and reflects badly on the judgement of the painter rather than the sitter. Lovely smile, though.

Equally, the plate accompanying van Gogh’s Cineraria’s (above), informs us that this painting was supposed to be lighter and more commercial to help sales. However, the plate concludes with the statement, “it is still not very colourful”. Contrasted with Monet, certainly.

There are also examples of the legitimisation of the flat landscape as a subject. Paul Gabriël’s 1898 work, Landschap bij Overschie (Polder with mills near Overschie) is a notable example (bottom left). Earlier one finds the more traditional approach to landscape painting such as Andreas Schelfhout’s Landschap met rechts een boerderij tussen hoge bomen (Landscape with farm between high trees) from 1817 (below right).

|

The museum also houses a collection of modern design artefacts. This collection is not really systematic nor specifically Dutch. There are collections of desk lamps, chairs, even door handles all tracing design innovations and materials. There are also plenty of metal and ceramic artefacts.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment