Archive for the ‘Casa-Museo de Colón’ Tag

Gran Canaria: museums, galleries and colonialism

Museums and galleries

Las Palmas – the capital of Gran Canaria – is home to at least four museums, three of which we visited.

Naturally there is a Columbus Museum (Casa-Museo de Colón – https://www.casadecolon.com/) that chronicles the significance of the islands for Columbus’s so-called discoveries. What we learned from the museum was how strategic the islands were for transatlantic crossings, particularly to the Caribbean. Columbus made four such crossings as captain and for each, the Canary Islands provided resources – food, water and labour. For example, for his first tour he needed, essentially, to refit his ships and fix a rudder.

The museum basically presents maps and artefacts in a reproduction of ship environments; for example, the Captain’s quarters showing a bed, desk (right). There is lots to learn about cartography – the evolution of maps is part of the story, of course. Visitors trace through the centuries how humanity moved from a flat earth to a globe and eventually got the shape of the continents right. I suppose cartography is the discovery that we can celebrate if not the conquering aspect of the voyages.

I give them credit for being focused and not getting distracted – Columbus is a big story. It is a lovely small but informative museum close to the cathedral in the historic centre of the city.

The top floor of the museum is an art gallery with time-limited exhibitions. At the time of our visit (29 November 2024) was a celebration of the work of a Canarian artist, Juan de Miranda. There is, as one might expect for a painter of his era, a lot of religion and aristocracy. But also some quirks. For example, I was intrigued by the portrait of St Lucia dated from around 1785. St Lucia is often depicted with eyes on plate. The meaning is not entirely clear but it is thought to reflect her lack of desire to marry. To be blind and eyeless – or to have one’s eyes literally disembodied – may well help her to avoid what she did not want!

CAAM – Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno

As one might expect, this is gallery of modern art (free entry). Over three floors there are three exhibitions dedicated to particular artists and themes. On our visit (4 December 2024) the artists were: British artist, Zak Ové; Canarian artist, Juan Hidalgo Codorniú and Teresa Arozena. Arozona’s work featured large prints of photographs showing the impact of tourism on the natural environment of the islands of the archipelagos (largely negative). Whilst they are recognisable for anyone who opens their eyes as they wander around the tourist spots (and possibly beyond), they are not particularly standout or framed in an interesting way. For example, shots of the dunes of Maspalomas fail to capture their scale (always difficult with photographs) and show engagingly the threat posed to it. I sense that we as tourists may have some better shots to take home with us.

Juan Hidalgo Codorniú had a lot to say about himself. A long career (he died in 2018) as a conceptual artist presented some interesting artefacts. Like for all conceptual artists, there are good, interesting and not-so-interesting pieces. Bizarrely in one of the galleries is a large area of simple pornography, and another a series of pictures of the artist with nude models. Let me put it this way, they are of their time (the latter the 70s), but unworthy of the exhibition more generally. One piece stood out, though. The depiction of the Earth in a condom (right) resonated. Though I suspect his meaning was different to mine – rather more sexual. It gave me a sense of the earth being emasculated/suffocated, particularly by men. But all we need is a little tear!

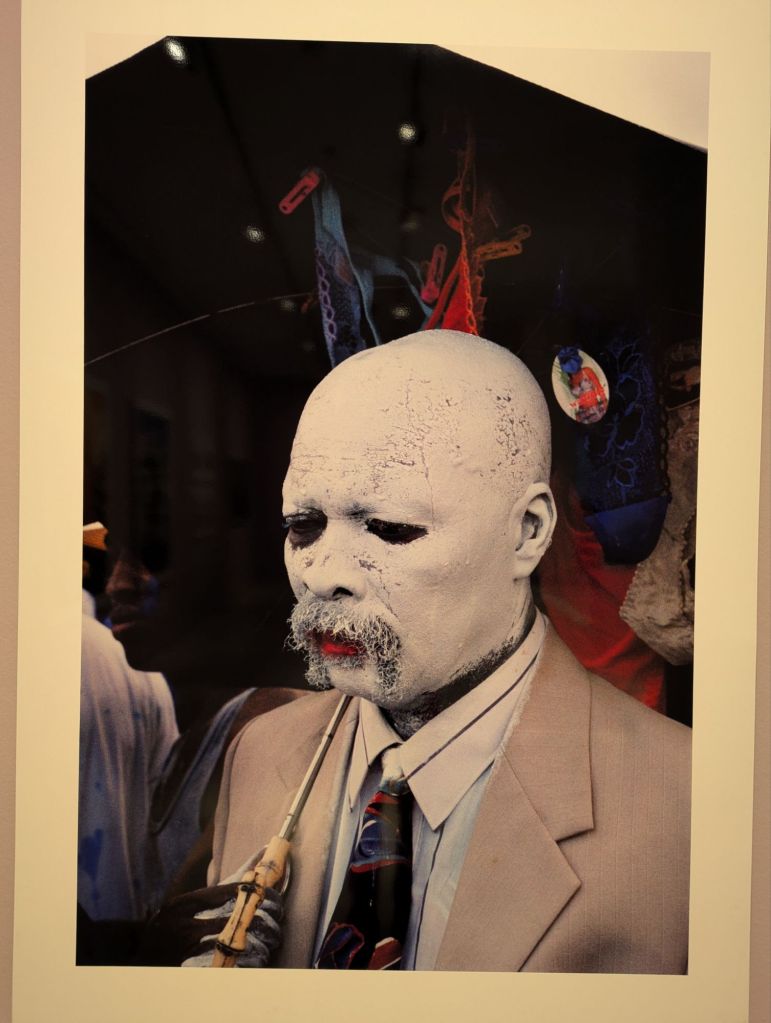

Finally, Zak Ové, whose collection here was streets ahead and eclectic. Ové’s father was also an artist and this work seemed like an extension across generations. Both men had a deep commitment to black rights. Seemingly the family lived adjacent to Michael X (aka Michael de Freitas) – there are some atmospheric photographs of him – one particular in Paddington Station, London. (He was eventually convicted of murder and executed in Port of Spain in 1975.) Images of the Notting Hill Carnival in the 60s also feature. Striking images include Evil is White (left) – though for me it could also include the adjective, male.

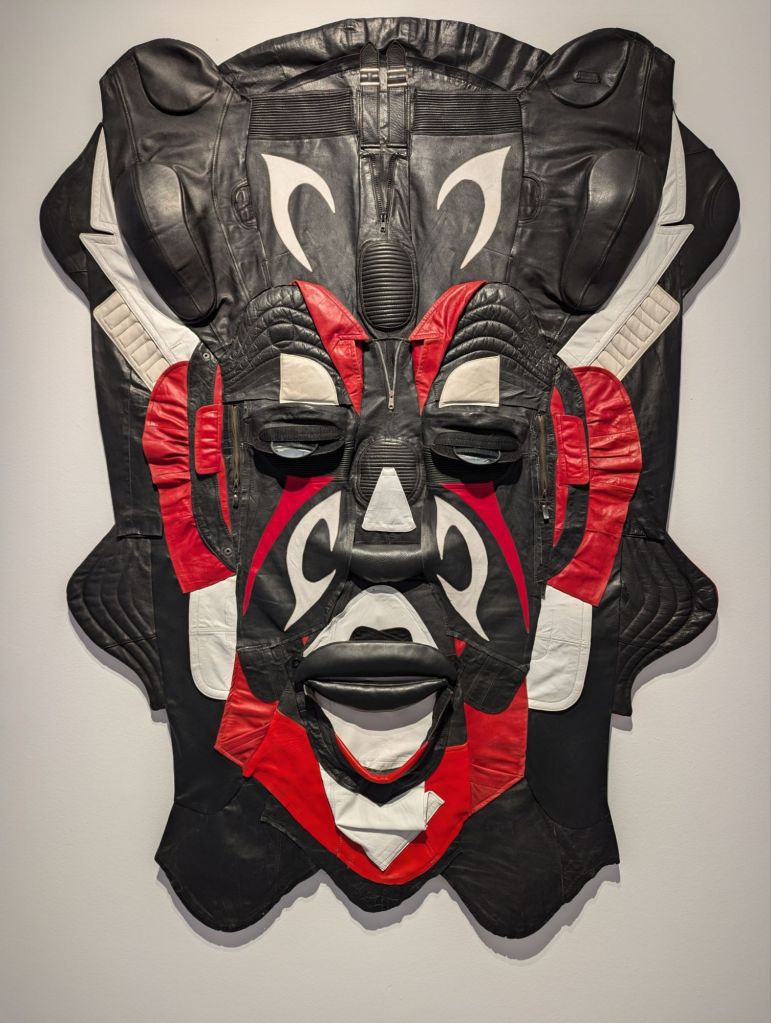

Ové is also a big user of re-used materials. One gallery demonstrates the fun and creativity associated with his approach. For example, for Fish (2009) he used brass instruments, rubber gloves and dolls. There is a series of masks made from old leather jackets dating form a 2024 collection.

Ultimately, this is a fascinating exhibition in an unlikely location. All the better for it.

Museo Canario

This museum is charming. It is made up of a private collection that was donated along with the building that charts the pre-history of the indigenous people of the island up to the point they were conquered by the Spanish. So it does not deal with the conquest. I bought a book to take up that story – it is complex, see later.

Charm comes in many forms – the building (left, the gift shop is housed in the collector’s library); the collection is disproportionately comprised of lots of bones and skulls; the staff (guaranteed not to leave without having visited the gift shop and bought something) and a curious but welcome adoption of technology (QR codes enable visitors to have an audio guide for each gallery in a selection of languages).

The story is one of arrival (by boat with a few animals and seeds); shelter (in caves and huts); clothing (tanning animal skins and weaving); food (agriculture, preparation/grinding of grains particularly barley); pottery (technology and types) and death (causes and funerals). There are representations of life dotted around the galleries. For example, pottery making (right).

The are other museums and galleries on the island. In Las Palmas, for example, there is El Museo Néstor, dedicated the work of the Gran Canarian artist Néstor Martín-Fernández de la Torre. Moreover, Gran Canaria is more than Las Palmas. There are important other towns in the north of the island such as Galdar.

Colonialism

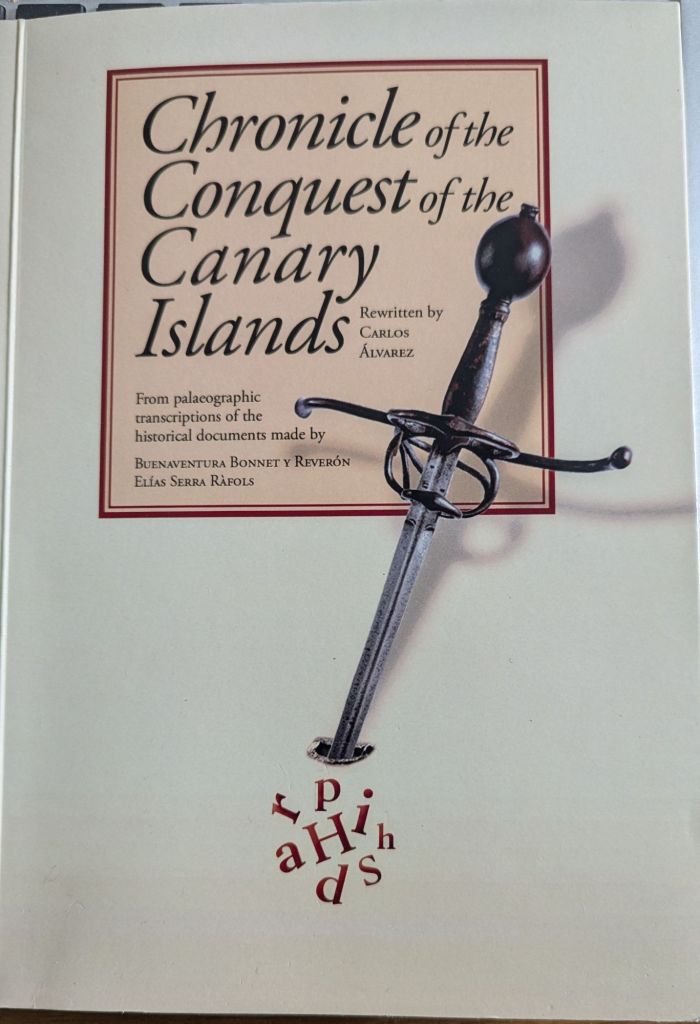

The colonial history of the islands seems to be something few museums want to address. The conquest of of the islands is not told in any depth. I had to do my own research and, so far, have relied on a single source, Carlos Alvarez’s book, Chronicle of the Conquest of the Canary Islands (left).

Alverez notes that there are a number of different accounts of this period (17th Century), none of which, of course, take account of the indigenous populations’ experiences. Alvarez has done a lot heavy lifting for us in checking the facts; for example, when false dates are presented, he make it explicit to us that it is false and why (if possible). In reading the book I conclude a number of things.

- The islands were not homogenous – geology, culture, natural resources. I sense this is still the case today.

- Colonialisation requires the cooperation of an indigenous population – on Lanzarote, the population surrendered rather quickly realising that they could not defeat the invaders. They agreed to be converted to Christianity as confirmation of their surrender.

- Of all of the islands, Gran Canaria was the most difficult to conquer (eventually in 1478). The final conquest was brutal – but conquistadors suffered high losses until Captain Don Juan Rejón arrived armed and prepared for his success attempt at conquest.

- The islands became property of the Spanish nobility (though the Portuguese had a go at wresting control by miliary force). They were traded between Spanish nobles. The owners and nobles were paranoid (fearful of losing their claims) and vindictive. This actually led to the “accidental” death of Captain Rejón an (unwelcome) unscheduled landing on La Gomera en route to La Palma (yet to be conquered). Consequently, the story of the conquest is told in the voice of the nobles – and their squabbles – rather than the voices of the indigenous people.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment