Archive for the ‘Environment’ Category

Gran Canaria – over land and sea, November 2024

OK, here we go. Low carbon travel. Train and ferry. Some facts.

Cost

Journey starts Saturday 17 November 2024. To fly from Gatwick Airport on that day would have come in at £45.00 (no luggage) – probably double that with the luggage I have taken that would need to go in the hold. Such pricing in the age of a climate emergency is obscene. By train:

London-Paris – £69.00 (standard class – average of return fare in November/December, considerably more in the summer or ahead of public holidays)

Hotel Paris – I was too late booking this for a Saturday evening. Overall cost £135. Hotel was Ibis Styles, Bercy. Breakfast included, and it was not bad. The room was tight but comfortable.

Paris – Madrid – £175.00 (standard class) – TGV to Barcelona and then Renfe to Madrid. The double-decker TGV is not particularly generous in terms of space, but not uncomfortable. The single-deck Renfe train was much more spacious but with no table (drop down rests were adequate for a laptop). We could not use the wifi because we could not see our ticket number (needed to register).

Hotel Madrid (Ibis Ventas) – £96.33 (incl. breakfast)

Madrid – Cádiz – £80 (standard class)

Hotel Cadiz (Soho Boutique Cadiz) £80 (incl. breakfast)

Cádiz – Gran Canaria – £91.10 (ferry – no cabin)

Taxi – Las Palmas de Gran Canaria – San Augustin – (£75.71) – Why taxi you ask? See below

Being in my sixties, I am not up for hostels, although I know that some budget travellers do so. Good for them, but I think I have reached a milestone. That said, in not selecting a cabin for the journey, we effectively slummed it, but the cost so far have been significant.

There are two of us so we need to double transport costs and share the hotel costs.

First leg

I’m pretty familiar with Eurostar. I travelled standard class on 16 November 2024 on the 1758 (retimed from 1801). I was able to work (the new drop down rests for stuff are now a bit wider). There are power sockets – UK and European. I have my own modem/internet for security reasons. The signal was pretty good throughout, including in the tunnel. In the past when I have connected to the Eurostar wifi, it has been pretty unreliable.

It cost me €2.15 to use the Paris Metro/RER to get from Gare du Nord to Gare de Lyon/Bercy. One can buy a card to load and reuse. Ticket machines take cash and cards.

Second leg

The next day (17 November 2024) we walked for 10 minutes from the hotel to Gare de Lyon and went to Hall 2 from where the trains depart. The QR codes on our phones or paper did not read. There was someone at the barrier to scan using their own reading machine. All good. We had two seats on the upper deck with a collapsible table usable only for the people sat closest to the window. There is a socket and wifi (below left).

The route taken by the train is pretty much rural France, but on reaching the Mediterranean, the scenery changes to on of salt marsh as it precariously meanders through the Parc Naturel Regional de la Narbonnaise (below right). The train is probably the best vantage point for seeing it as the train runs over what seems to be a causeway.

Warning, however, whilst writing this blog entry my case located by the entrance to the carriage was stolen. My advice is either to chain it to the bars or locate your case inside the carriage – there are some internal luggage racks.

The RENFE train to Madrid was directly opposite the arrival platform of the incoming TGV. It was that simple. Though there are a few challenges. We bought our tickets on RailEurope.com. The pdf that is made available on the app is unreadable by anyone with less-than x-ray sight. The train manager had a record of the ticket, so we were fine. It seems also possible to print tickets from ticket machines providing one has a PNR number that was clearly stated on the itinerary confirmation.

We then looked to buy tickets for the next leg, Madrid – Cádiz. We tried the machines – ticket buying by non-Spanish citizens is not so easy. Each traveller needs to insert their passport number. We got so far in the process (give yourself 10 minutes) before we were thrown out of the system whilst trying to pay. We did then find the staffed Renfe ticket office on the first floor and bought them in the traditional way, but passports are still needed. And the ticket office sales person found the system equally cumbersome. Our passport details had to be put in twice!

Then on to the Metro. Two lines, first 1 (blue) to Sol and then 2 (red) to Ventas. Buying tickets is easy, but you have to buy a card and load it with as many journeys as you need. In our case one centre ticket. Each centre area ticket cost €2.50 with the card. For the first charge, I think the card costs €2 (extra). On the way back to the station the following day, 18 November, we just loaded the cards. Note the machines are cashless. We ate in a nearby Lebanese restaurant. Portions were huge – salad, falafel, spicey patata and vegetal mousaka.

The hotel is next to the bull ring (left) – a constant reminder that there are some residual bloodthirsty passions in Europe. (The British as much as the Spanish – though not in such grand areas.)

Third leg

Monday 18 November is another train journey – about 4 1/2 hours to Cádiz. There is a fast and direct service roughly every 3 hours. It think it can also be done in two legs if needed: one to Seville and then Seville – Cádiz. The trains are spacious (standard class). Each seat has a socket (though mine did not work). There is room for a laptop to be opened and used. The wifi on the train is not working. Though my modem is fine. Similar to Paris, Madrid has distinct boarding gates. Passengers are advised to get there 30 minutes before departure – all baggage is scanned (unlike Paris). It takes about 10 minutes to pass through.

Incidentally, I bought a new case at the station, a t-shirt, shirt, a pair of socks and a sweater to keep me going. I discovered that I did have some underwear in my rucksack.

For a change we arrived at our destination in daylight. We checked into our hotel – probably one of the best we have ever enjoyed – the Soho Boutique Hotel. We had a suite. It was sensational. The breakfast was additional, but worth it. The spread was varied ranging from breads, pastries, cereals, cheeses, meats and fruit.

We bought a few more items in the town:

- food to take onboard – correctly assuming that the onboard catering might be a little unapetising

- Some eye protection (my prescription sunglasses were in the stolen case)

- some trousers and a gilet from a male clothing retailer and shorts, leggings, t-shirts and underwear at an unexpected-to-find branch of Decathlon.

We ate in a Latin-inspired restaurant in the town. The restaurant – Más Que La Cresta – is not exclusively vegan, but the options are good. We took a selection of starters as tapas; though the vegan burgers were certainly enticing, burgers are not quite our thing.

Fourth leg

The ferry terminal is about a 15 minute walk from the entrance to the port. Foot passenger enter the office through which they pass security control and then enter a taxi to drive to- and then in-to the ferry. We did not take a cabin – trying to keep down the costs somewhere – so slept in the reclining seat area on deck 7. For the first part of the journey we sat on the deck in the sunshine. The ferry crosses the shipping route from the Mediterranean west. I trust they have some communication and understanding that ferries operate against the dominant shipping route. It is a reminder that the seas are equally colonised by humans. And on the deck, the exhaust from the ferry reminds us that there are still greenhouse gases being expelled into the environment.

The ferry has a small shop that sells the basics – cigarettes and soap. There is a bar/café and then the self- service restaurant. Not much more. It is unlike the ferry to Rotterdam from Hull which has cinemas and a casino (not that a casino is of much interest to us).

Sleeping – without a cabin, there are rows (2-3-2) of reclinable seats on decks 5 and 7 (right). Deck 7 is the quiet level. What we have realised is that this ferry carries some very seasoned travellers, many of them young, who bring mattresses, airbeds, sleeping bags and food to microwave (the restaurant has a public microwave for use). There is no washing up area, though. So the seasoned travellers often sleep horizontally on any available floor (there are signs all around forbidding this, of course). It is, I think, also the case that this is not a party ship. People are here to sleep, not to party (that is probably saved for the islands).

Did I sleep…yes. It was quiet. People slept. Though in the summer it might get more chaotic with so many floor sleeepers. The reclinables are least comfortable, I found, when reclined (they do not recline too much). I reverted to normal position. A pillow of some kind is needed. That doesn’t mean that I am not looking forward to a bed on arrival.

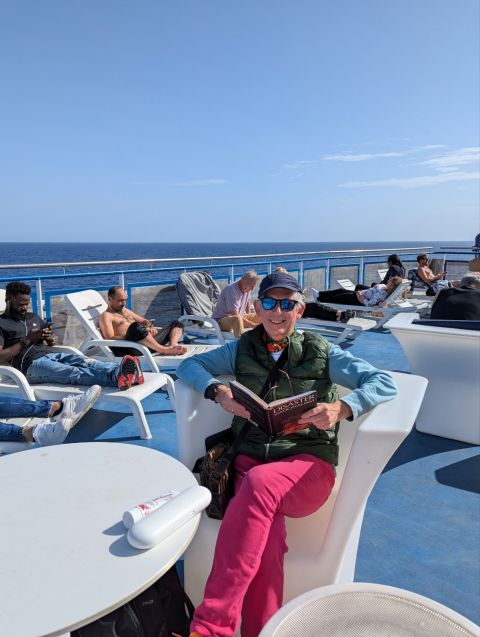

For the day, I was on deck for much of the time (left). The sun was warm and I had a book. Working is not so easy as the ship is really not geared up for business. The sockets are few – and in demand for mobile recharging. There is a small cordoned-off area in the restaurant that could act as a business space. It does have sockets, but I only counted four, and they were not well spaced around the room either. In the end I went to work in the restaurant in-between sittings (breakfast, lunch and dinner). Talking of which, we did take breakfast. It was not bad actually. And not expensive. For €12.50 we had cereal, bread, egg, yoghurt, tortilla and coffee. We are not sure whether it was accurately calculated. But hey.

We were scheduled to dock at midnight…in the end it was 0130 GMT. We were out by about 0200. But what then? Cadiz is easy, the port is adjacent to the town and walkable. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria port is quite large, not walkable and relatively deserted at 0200. There was no shuttle bus, no taxi rank. My beloved was armed with a taxi phone number but more than once – without perfect Spanish – they just put the phone down on us. I walked back to the ferry to ask one of the personnel if they could speak for us. We had a volunteer whose intervention magically summoned a taxi that arrived after about 10 minutes. Uber is on the island – download the app before you travel. Anyway, the drive was approximately 45 minutes – fast because there was little on the roads (which are superior to anything in the UK – not a pothole to be seen). The fare was €90 to San Augustin – 55km. Journey end.

Reflections

I wanted to test the feasibility of getting to the island by land and sea and be productive in the process. Whilst I may be on holiday, I still want to engage in some academic work – I am an academic after all. All travel raises questions that warrant answers. I have never regarded travel time as a waste. I do think my efforts here were thwarted by the transport operators – notwithstanding the theft of a bag. Here are the key challenges:

- Cost – it is significantly more expensive to travel overland than by air. The journey cost overall was £802.14. That is at least eight times what it would cost to fly. We could cut out the hotels – do Paris to Cadiz in a single day starting very early in the morning. That is a tough day and all the connections need to work.

- Time – I wanted to be productive and connected. It was ideal for reading books and academic papers, not so good for writing. Observations:

- I could not connect to the internet on Renfe between Barcelona and Madrid because users need their ticket number. This was unreadable on my ticket from RailEurope. That said, for security, I use my own dongle with European roaming, which worked fine. I did use about 21/2 Gb.

- The (un)complementary internet on the ferry was very poor. And because we were sailing, there was no mobile signal (I feared, too, that if there was, it would be Moroccan, and therefore elicit extra roaming costs). I could have bought a better internet package from the operator, though. I did not because I had lost my credit card in the bag theft.

- As noted, there is no dedicated workspace onboard.

- Foot passengers on ferries are poorly served. The situation at the port of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria was a problem. There was absolutely no provision for us at the port. And being so late, it leaves stranded passengers vulnerable. This is not universal. Other ferry journeys that we have taken have been better served. Hoek van Holland has its own railway station! Europoort had coaches to take passengers to Rotterdam (or used to).

What needs to be done

- Sort out ticketing…

- Buying European train tickets is way too complicated, especially across borders. We used Rail Europe, but the tickets issued were unreadable by station and train staff.

- Adding to that, buying tickets in Spain either by machine or at a staffed ticket office is slow and cumbersome. Passports are needed for non-Spanish travellers and it can take an inordinate amount of time to get issued with a ticket. On the machines, we twice got ejected and had to start again.

- Wifi…

- I am happy to use my dongle for security reasons, but the ferry wifi was poor by any standard. Even basic searching was difficult or impossible. The wifi would shut off in any case after 30 minutes or so and it was necessary to log in again, including reading the terms and conditions.

- Make provision for work – dedicated space, sockets, reliable wifi. I know the argument – there is no demand. But there is no demand because there is no provision, arguably. Equally, the ferry would be an ideal place for a conference, workshop, briefings, etc.

- Treat foot passengers with respect. Ensure that they can embark and disembark safely. And do not leave them stranded at a port in the middle of the night. That is truly shocking.

Getting back

We flew back! It was not the original intention, for sure. I made the decision when we got on the ferry from Cádiz. I am not advocating flying – my overland and sea days are not over, far from it. Indeed, the flight was long, cramped, hot and involved airports. However, three key things swung it for me (a further two factors made me feel slightly more sanguine).

- The timings of ferries back relative to my need to be at my desk on 9 December meant that the time on the island would be much shorter. In order safely to get back by 9 December, I would need to leave the island on 1 December 2024. That ferry is scheduled to be 43 hours. Having taken 5 days to get to the island, to leave after just over a week seemed rather punitive (bearing in mind I am working throughout the period January to August inclusive and this is my summer holiday).

- The experience getting here was not the best – from having my bag stolen to the facilities on the ferry and the restaurant menus.

- Cost – I had to spend quite a bit of money replacing some of the things I had lost particularly my clothes.

- Carbon – I am trying to be a good citizen, but I am not perfect. Though I am reminded by some pioneers of low carbon working of studies relating to carbon generated by flying, in particular the contrast between short haul and long haul. That is not to say that I am going suddenly to start flying again as I had done prior to Covid (i.e. every week). Here is a quote based on work by Frédéric Dobruszkes, Giulo Mattioli and Enzo Gozzoli “flights of less than 500km account for 26.7% of flights, but only 5.2% of fuel burnt; while flights of 4000km or more account for just 5.1% of flights, but 39% of fuel burnt. This tallies with AEF’s (The Aviation Environment Federation) findings that shows that in terms of carbon emitted from flights from the UK to destinations around the world, the worst offenders are indeed long-haul – in top place is the US with 23.6% of the UK’s international flight emissions (10.6Mt), and Dubai with 6.7%.” You can read the summary article, “The Elephant in the Middle Aisle” here.

- Finally, I picked up an injury in the final week on the island (see later entry) that would have made overland very difficult, painful and dangerous. On that basis, too, I can safely say that disabled travellers are much better served by airlines (though there are some horror stories) than overland across borders and modes.

Decarbonisation milestone

It has taken three years to get there, but I have reached a decarbonisation milestone. It started with six photovoltaic cells on my roof and 6kW of battery storage. I then invested in an induction hob. Then, the big one, the heat pump. Which is now doing an amazing job at keeping the house warm and supplying hot water. It is a different experience to my gas boiler and super hot radiators. The radiators stay ambient.

Anyway, finally, today I said goodbye to my diesel van (why did I have a diesel van in the first place you might ask?). I have sold it, so it will still be burning fossil fuels and emitting greenhouse gases. But I felt that in selling it I may be tempering demand for new vehicles. Even this old van has embedded carbon from its manufacture.

Where to next? What more can I do? Well, there remains plenty of scope. First, I need to do a full audit of my life and then create for myself a carbon reduction plan! I will report further here in due course.

Summer Festivals – can they survive climate change?

Late summer bank holiday weekend, 2024. The Leeds and Reading festivals are scheduled as normal. But normal does not really exist any more. It used to be possible to put on such a festival in August with some confidence that, whilst it may rain, festival goers will at worst be wet. But no longer.

On 23 August 2024, the Leeds part of the festival reported that it had “lost” two stages. The BBC stage and the Chevron stage were withdrawn from the festival programme. The Aux stage was reopened. Wind was a particular problem making camping really challenging (as if camping is not challenging enough already, see above after the storm).

The cause? English weather? Well, weather, probably. In the autumn and winter we had an unprecedented number of so-called named storms – storms that will cause disruption, however defined. This bank holiday weekend “welcomed” (Storm) Lilian to the Leeds festival. Named storms have only been with us since 2015. But I do not recall life-threatening situations at British music festivals in the past from storms (I cannot find evidence – though famously the Woodstock Festival in 1969 offered up a dangerous electrical storm on its third day). The cause, according to the UK Met Office is the behaviour of the Jet Stream – column of fast-moving air that usually sits to the North of the UK in the summer but has shifted frequently in recent years to sit directly above the UK, and particularly the North West of England and Scotland. The consequence is that the particularly moist air above the Atlantic is directed to the UK and is deposited over the country when it meets the land. To make matters worse – and to illustrate the interconnectedness of our weather and climate – unusual weather patterns over North America (sinking cold air) have given additional energy to the Jet Stream.

OK, let us talk about climate change. As expected, there is some reluctance on the part of climate scientist and meteorologists to ascribe causality – a warming planet equals more storms. Named storms are an irrelevance – they are merely a media mechanism to raise awareness that citizens need to be careful in what they do in the face of a named storm. For example, don’t go to outdoor music festivals or hike in the mountains. If you can avoid it. There are data relating to rainfall (certainly increasing) and wind leading to tidal surges and flooding. The UK’s positioning in the north west of Europe leaves the land mass open to exposure to Atlantic weather and the effects of small changes in the positioning of the Jet Stream.

The business implications are immense. Festival organisers (and owners of the brands), now need to consider more carefully how to host such events safely. It is not clear yet, in the Leeds case this year, as to why two stages were withdrawn completely. Were the stages irreparably damaged? Were they merely discovered to be unsafe after the wind (in which case a rethink is needed on stage design)? And what about insurance? What if festivals become uninsurable?

Burtynsky – Extraction/Abstraction (Saatchi Gallery, April 2024)

I am not a little impressed by photographers that work at scale. I have been the subject of one such photographer, Spencer Tunick, in London. His subjects were always without clothes. It was late April 2003. There were thousands of us. It was quite an experience. And for the exhibitionists amongst us, it was possible to visit the adjacent Saatchi Gallery (then in the old County Hall building) before re-robing.

Then there is the wife-and-husband couple of Hilla and Bernd Becher who spent their careers taking black and white photographs of industrial sites and machinery such as mines, steel plants, water towers, etc. I suppose what really impressed me was the fact that they hit on recording something that I, as a child, thought would be there forever and they, not being children, knew they would not. Hence I regret not taking more photographs of buses, trains and shops in my home town when I was growing up. But there you go.

And then there is American photographer, Edward Burtynsky. His father worked in a steel plant. Burtynsky himself funded his studies by working in that very same plant for a sufficiently long time for him to latch on to the idea that such plants may provide a subject for his photographic career. As it turned out, his most influential work is not the plant itself, rather the extraction of the raw materials that ended up in those plants – iron ore, copper, coal, etc. For that reason, this exhibition was a must (subject to my busy schedule).

I’ve now been and the images are extraordinary. They are presented in very large format and, mostly, as aerial shots, look nothing like what they depict. They come across as abstract art – hence the title of the exhibition. On the whole, however, they are not art, they are a record of environmental destruction. There are a few exceptions where the extraordinary patterns actually record profuse wildlife habits such as the landscape around Cadiz in Southern Spain (above left).

Like most artists Burtynsky has a team working for him. The drone technology he uses relies on an expert to make them fit-for-purpose. For example, high altitude photography creates a challenge to get sufficient lift to get the drone in the air (there is a part of the upstairs gallery that reveal his methods, equipment and projects).

By far the most interesting galleries show the scale of the impacts on the landscape of mining – whether it be the scars of the opencast mines themselves, or the spoil heaps or tailing ponds. With the possible exception of coal, the ores and minerals are not neatly packaged by nature for extraction. They require significant refining, often with toxic chemicals that tend to be dispersed into the natural environment. At scale.

So, anyone with a diamond may well have contributed to the large deposits of “waste” displaced to find diamonds. The picture (above right) is of the Wesselton Diamond Mine, Kimberley, Northern Cape, South Africa (2018). If readers look closely a conveyor belt can be seen on which the tailings are transferred to the pond.

A metal that we hear so much about for the necessary electrification of our world is lithium. There are a number of extraction methods for lithium; however, one mine in the Atacama Desert in Chile (left) pumps up a liquid from beneath a salt flat into ponds. The ponds are exposed to the sun, the liquid evaporates and the lithium carbonate is then harvested, before being processed. And then there’s agriculture.

Do readers ever go to the supermarket and see that broccoli or some other vegetable is from Spain and think, “ah, that’s fine”? Well, maybe it is not fine. Burtynsky shows the true scale of such operations and their impact on the environment (right). The greenhouses on the Almeria Peninsular harvest between 2.5 and 3.5 million tons of fruits and vegetables annually, including “out-of-season”. These greenhouses require huge amounts of precious water along with a heavy use of chemicals. Climate change is making the water situation more difficult.

I could go on. I have one last thought. Scale is a problem for us as humans. Burtynsky has taken some revealing pictures of people at work (left) of particular alarm is a picture showing people working in a chicken processing factory in China (everyone wears pink, left). The scale here is twofold really. First, the people. The thought of 8/10 hours per day chopping up chickens is hard to comprehend. We try to present work as something that offers meaning to humans and the opportunity to work with others and exchange ideas, thoughts and stories. There is not much of that going on in this factory. And then there is the chickens. The sheer scale of this one factory tells of the huge number of chickens slaughtered daily to keep these people employed (and presumably fed).

This is an exhibition at scale. Bigger than I thought it would be. It took about 21/2 hours to get through and that included a 30 minute film at scale (worth the visit, for sure). It is thought provoking. There’s a big chalk board to write one’s thoughts – mostly about human stupidity. And then there is a shop in which visitors can contribute to the further exhaustion of finite resources. I had a poster in my hand. And then I put it down and left.

Nothing in this exhibition is human scale. Arguably the Bechers’ work in the 1960s was a little more human scale. Spencer Tunick’s work is by definition human scale.

If readers want to know more about extraction, I suggest Ed Conway’s book, The Material World.

Banksy’s artworks

Gio Iozzi asks, why does it take an artist to expose the assault on our urban trees? This in light of Banksy’s latest addition to his portfolio recently found in Finsbury Park, London. It is an interesting work, and slightly different from his usual work, as it requires a significant prop. A tree. The tree is special because it has been “pollarded” – severely pruned in normal parlance. It has been pollarded because, according to the Council (the owners of the land on which the tree stands) it was diseased. It is a cherry tree, and they do not, it seems, respond well to radical pruning. There is also a question of whether diseased trees need to be pruned or felled. Many of us are a little diseased, but we do not lob off all of our limbs to deal with it. Or at least not as the first option.

It seems that Banksy, whoever he is, saw the opportunity to provide this sad tree with leaves by painting them – or spray painting them – onto an adjacent side wall. Viewed from one angle, the tree looks healthy and with full plumage. And like all Banksy artwork, there’s a message.

Art is there for the receiver to interpret, even if the artist provides the artwork with their own meaning. So we take liberties – rightly – with interpretations. So let us interpret this widely. This is a dual statement about the state of our urban trees and about climate change. Urban trees are under threat, just at a the time when we need them most. Our cities are getting hotter. Trees provide shade, for sure. But they also cool the air. Even diseased ones. So much urban landscape is devoid of trees. Devoid of ways of cooling and, increasingly, draining.

More broadly the onslaught against the planet’s forest ecosystems is relentless. The cutting and burning of the Amazon has slowed, but not stopped. Forests elsewhere in Indonesia and Africa are also in retreat. In Brazil particularly to provide land and feed for cattle. So not only do we lose carbon-capturing trees, we also increase our emissions through bovines, notorious methane producers. All because we want to eat large quantities of beef.

In response to Iozzi’s opening question about artists, I respond simply by saying, it is what artists do. It is why they are an essential part of the democratic process. Throughout history artists (not all, for sure) have made statements about society, power and morals. Degenerate art in Nazi Germany was degenerate for a reason. Artists have been subtle sometimes in their representations. Messages that eluded the censors because they were unable adequately to understand what they were actually looking at. Even Picasso, not known for his political statements, produced his masterpiece, Guernica, to say something to the perpetrators of the destruction of the Spanish town in 1937. Famously when asked by a Nazi Officer at his Paris studio whether he had “done” this painting, his reply was “no, you did this”.

To add value to the picture and to the metaphor, Islington Council put a protective fence around the work, but within 48 hours it had been defaced. I am pretty sure that Banksky was smiling. I rest my case.

Original picture source: https://twitter.com/IslingtonBC/status/1769722470355828821/photo/1

The Garrick Club

The Guardian’s recent exposé on the Garrick Club in London is troubling. It took a data breach for us to know who the club’s members are.

Not only is this a “gentlemen’s” club, it is also an elite club where state/government policies are discussed and made. As a man I do not have the resources to join and even if I did, I think it is unlikely that existing members would nominate me. I could at least try; but if I was female, it would be harder despite David Pannick KC’s best efforts to justify its existence. There is, argues Pannick, nothing in the language that bars women – even the word “gentleman” seemingly has a defence. Here is Pannick quoted in the Guardian article: “[t]he term ‘gentlemanly’ is plainly being used here in the sense of the meaning ‘[o]f a pastime, behaviour or thing’ that is ‘of high quality; excellent’”. I’m not about to buy that. It is not surprising that lawyers can offer such a defence as we discover that a large tranche of senior [read influential] figures in the profession are members. Many environmental campaigners, for example, have found themselves judged by them. And that raises bigger questions about the profession itself.

Picture: By Cambridge Law Faculty – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxB59qEi6i0, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=104993515

One Gallery, climate messages

I recently went to Tate Britain in London. The gallery is home to many of my “friends” – a strange idea, but I always relax when I see the images in the flesh, as it were. In recent times, however, I have visited galleries with very different intentions. I want to know how – and if – art delivers a climate message, either by chronicling environmental decline or in championing its salvation. Both are true, of course.

On this visit, March 2023, I set myself the challenge of cataloguing one gallery (one gallery and bit, to be honest) for its climate message. Here is what I found.

Of course, LS Lowry has a story to tell. I always remember Brian and Michael’s song, Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs (no women for some reason). I even bought that record. But revisiting Industrial Landscape (left) I noticed other things in the picture not seen before (that is the beauty of art, there is always something new in the familiar to see. There are not too many people in this image – a few in front of the houses and along the central street leading to the factories. I see the trains on the viaduct and the barges on the aqueduct (if I see it correctly). What was new was the colour of the chimney emissions. They are not just sooty, they are toxic red, particularly those in the background. I wonder!

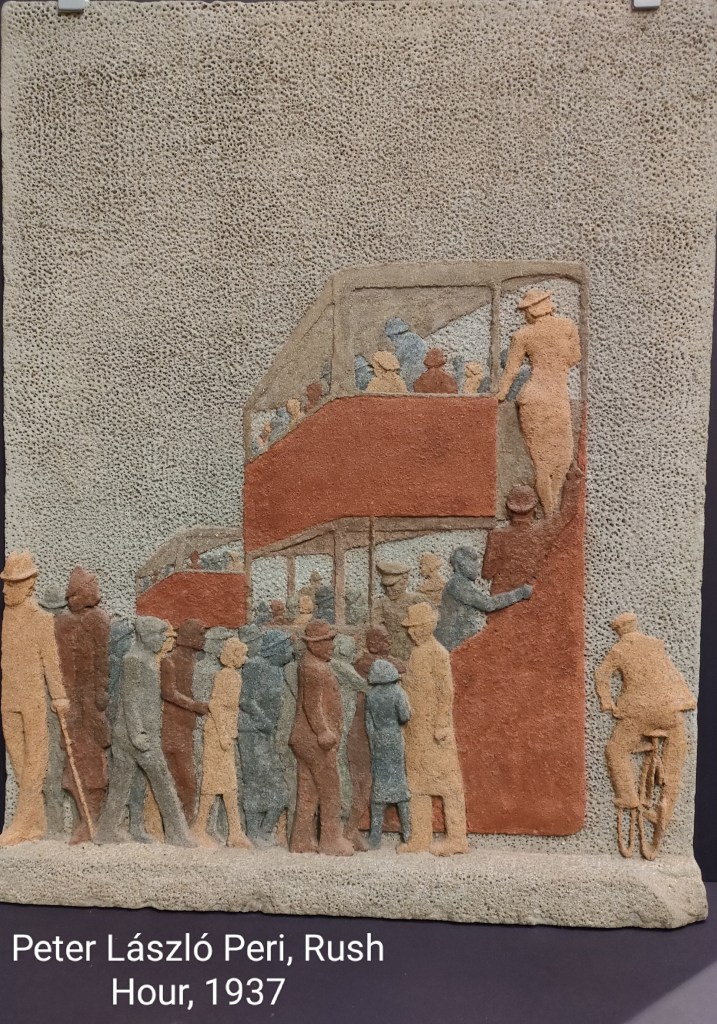

Slightly earlier (1937) the work of Peter László Peri. Peri does not paint, he uses stone to represent urban life. His rush hour incorporates one of my favourite images, that of the double-decker London bus. The image is effectively carved from a block of stone coloured in a rudimentary way; for example, copper red and earth brown. It is orderly and very English. On the one hand it looks like a depiction of the daily drudge of travel to-and-from work. But Peri sought to represent positively industrial society, so perhaps the woman climbing to the top deck of the bus represents progressive views about woman and work? There is also the cyclist taking on the diesel bus and wider traffic.

It is perhaps not surprising that Peri chose stone – he had been a apprenticed brick layer as well as a student of architecture in his birth city of Budapest, Hungary. Moreover, he was associated with the Constructivist movement dedicated to representing modern industrial society formed in Germany in 1915.

Peri arrived in England in 1933 – he was not in any way popular with the Nazis being both Jewish and a Communist.

Cliffe Rowe’s picture, Street Scene (left) depicts a pram (presumably for the health benefit of the baby inside) outside a terraced house. There is a woman sat of the step knitting (oddly revealing her underwear) and a man in shorts reading a newspaper. How typical this was, I do not know, but it seems to be a scene of aspiration. There is street lighting. Net curtains. In 1930, Rowe travelled to the Soviet Union and stayed for 18 months. He was impressed with the Soviets’ use of art to support the working class struggle; though he may have been taken in simply by propaganda. That said, on his return to England he became a founder member of the Artists’ International Association (along with Peri) which used art to oppose fascism.

Predating both of these artists was Winnifred Knights. Her picture The Deluge (1920, right) has a very contemporary interpretation. Men and woman either flee or resist rising water in a representation of the Biblical flood in Genesis. Clearly a contemporary interpretation – or translation – is climate change and rising sea levels. Not an act of God, but an act of humanity against itself (and all other inhabitants of the planet).

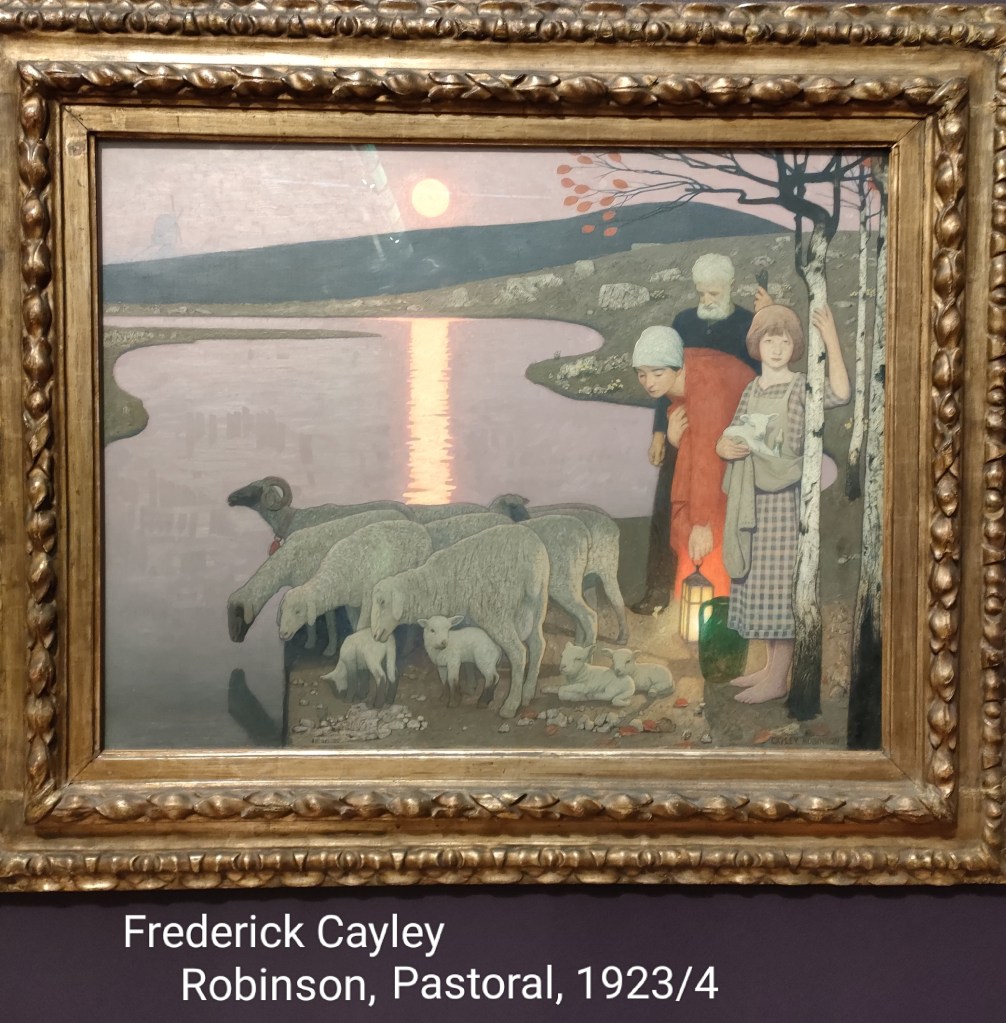

To see what we forfeit in the industrialisation of economies, we can draw on some of the more conservative images of the period. Frederick Cayley Robinson’s Pastoral (left) is a good example from the gallery. It depicts a family and a flock of sheep by the waterside. A child holds a lamb as a symbol of rebirth. It is rural idyll in the post WWI world. It is rural, but not idyllic. There is only a windmill as a concession to technology – enough to enable this simple life. Of course, it is not where we ended up.

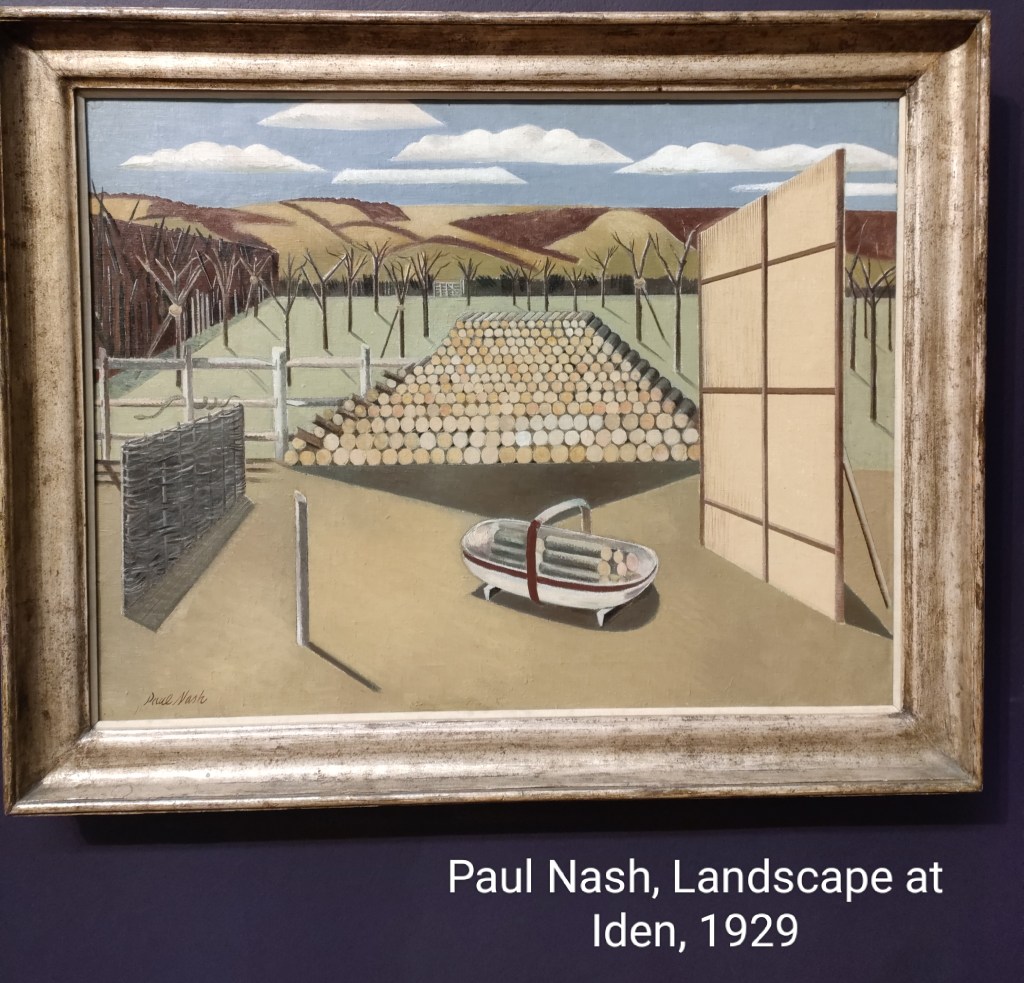

My penultimate choice is work by probably my favourite artist, Paul Nash. Nash was greatly affected by his experience of WWI. On my visit for the first time I saw Landscape at Iden (1929). His geometric shapes “blend” with the landscape, and in this case with felled trees. The felled trees are interpreted to mean lost souls in the war. The snake on the fence is easy to miss. It can represent evil, for sure (it was a serpent that tempted Eve to eat the apple), but pharmacies use the symbol of the serpent to represent healing. In Nash’s work it could go either or both ways, I sense. Whatever they are meant to represent, war, through history, has impacted on the natural environment. Despoiling it with armaments, clearings and extraction. I have not entirely convinced myself that this picture is translatable, but his pictures always leave me feeling understood.

I’m going to take a liberty with my next choice – reinterpreting a living artist, David Hockney. His picture The Bigger Splash (1967) is a representation of the water’s response to a dive into a pool. I have always seen Hockney’s California period as a reflection of unreality (Hockney admits his splash is not realistic) – the good life that comes from industrial society that is endured by others, particularly in the industrial Eastern USA. I feel vindicated inasmuch as when Hockney returned to the UK he bought a house close to where I was brought up in East Yorkshire. Those images are most certainly about the land, its plants and change.

Summer 2022: the €9 ticket holiday – 2

Art

Holidays often feature art – why would they not? In this journey we’ve been to Berlin, Elblᶏg and Dresden. The latter two are provincial cities with their own take on what should be shown and what not. And how.

Elblᶏg surprised me. The art is everywhere in the public realm. Seemingly in 1965 a number of artists were commissioned to make art and place it just about everywhere in the city. Examples of the work are below, but what it does to a place is interesting. In some cities the art would be defaced, damaged or vandalised. I saw none of this. 1965 – that’s 57 years! I assume that the art reflects the town and its people. Most of the artwork is made of steel, yet compelling. Maybe no one notices it, but it is there.

In Dresden, art has a very different role. Dresden celebrates its kings or “electors” The Residenz – effectively the palace of the elector August the Strong (apocryphally he can snap a horse shoe by his brute strength). He was strong, but probably not in this sense. His art collection – or treasures – illustrate just what constituted his ego. There is no question that most of the objects in the galleries are exquisite. I simply cannot imagine how most of them were decorated. Some of them were linked to what was probably 17th Century high technology such as clocks. The example on the left is a roll-ball clock. The ball is rock crystal and it rolls down the tower. It takes exactly one minute. Inside, seemingly, another ball is raised “emporgehoben” (whatever that is supposed to mean in reality) which moves on the minute hand. Saturn then strikes a bell, and twice a day the musicians raised their wind instruments and an organ played a melody. It is an extraordinary piece; but somehow I prefer time keeping to be a little simpler, at least in its reporting.

The jewels are one thing, the ivory is quite another. I have to say I’ve never seen so much carved ivory in one place. It is quite sickening. The carving is amazing, however. Take this frigate (right). I do not know how many elephants died for this piece, but everything apart from one feature is obscene. It dates from 1620 and bears the signature of Jacob Zeller. Of course the frigate is supported by the carved figure of Neptune. The sails are not ivory, nor the strings. But there 50 or so small human figures climbing those ropes. They are extraordinary.

There is an ivory clock to rival the jewelled example above. But quite the most sickening is to carve an elephant from ivory (left). There’s a receipt for its purchase in 1731. It is actually four perfume bottles hidden the castle turrets. What gets me particularly is the failure of the gallery to say anything about the exploitation of nature. These are simply curated as exquisite objects of great value.

It was not only elephants from the natural world that were exploited. Here is something I absolutely did not know, coral was a material for artists and treasures in this period. The bizarre figure on the right is seemingly a drinking vessel in the shape of the nymph Daphne who metamorphosised into a tree (coral) to escape Apollo’s “harassment”. It is not just one piece, there’s lots of it in this gallery. Not a word about how the coral was gathered and where from.

But there’s more. There are some deeply troubling figures of black people. I am not going to upload the photos of a sedan chair occupied by an ivory Venus and carried by “Hottentots”. Venus is attributed to court sculptor Balthasar Permoser (1738 or so) and the figures to court jeweller Gottfried Döring.

I left this gallery feeling troubled and dissatisfied with the curation. They must do better.

The Albertinum is another gallery in the historic centre of Dresden. There is some interesting stuff here. Sculpture is not usually my thing, but it has a number of examples of art that was deemed by the Nazis as “degenerate”. For example, Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s “Kneeling Woman” (1911, left) which is quite extraordinary, but obviously too extraordinary for the Nazis. Then oddly there is a piece by Barbara Hepworth, Ascending form Gloria, 1958). Odder still is a decorated wooden crate ascribed to Jean-Michel Basquiat (I am probably wrongly describing it). There are a couple of contrasting pieces by Tony Cragg – a wooden abstract sculpture and a cube made up of compressed rectangular objects ranging from lever-arch files to old VHS video players.

The upper floors are full of fine art. Again, keeping to the theme of degeneracy, climate and perhaps art that captures some of the potential consequences of unchecked warming, I start with Ernst Ludwig Kirschner’s Street Scene with Hairdresser Salon (Straβenbild vor dem Friseurladen, 1926). Kirschner was part of a group of artists known as the Brücke Group. Like many art movements the members were all against “old establishment forces” and following artistic rules. The bright colouring is an example. So shocking were the paintings that they could not be purchased by the City. Eventually, they became accepted and acceptable, only to find them labelled as degenerate in 1937.

What was not degenerate was Hermann Carmiencke’s Holsteiner Mühe (1836, Holstein Mill). I choose this because water was a natural source of sustainable motive power. The steam engine was arguably introduced to break the collective power of labour and because the water resource ultimately could not be shared by the direct owners of capital.

Finally from the Albertinum I selected Wilhelm Lachnit’s Der Tod von Dresden (1945, The Death of Dresden). It is, of course, a reflection on the human suffering arising from the second-world war. The climate crisis will bring its own deprivations and a fight for resources. We will see these times again, I fear.

A quick word on Dresden. The historic centre was essentially rebuilt from 1985. Many of the historic buildings were left as shells and rebuilt using plans and authentic materials. It was an exceptional achievement and good on the eye; the Semper Opera House, for example (above left). But this is not a city preparing for rising temperatures. Whilst there are green spaces, this central area is totally devoid of natural shade. The new centre around the railway station is largely concrete-based retail. Could be anywhere.

Meanwhile in Berlin, we visited the Nationalgalerie. I was taken by the work of Adolph Menzel. He obviously earned his money painting portraits of rich men, but he also had much to say about contemporary issues of the time – the mid 19th century. He is, by definition, a contemporary of Turner. And Menzel’s picture Die Berlin-Potsdamer Eisenbahn (1847) has some similarity to Turner’s Rain Steam and Speed which dates from 1844.

Menzel also painted a number of factory scenes – Flax Spinners, dangerous women’s work. The only safety equipment is clogs on their feet.

Contrast this image with that of his painting Flötenkonzert Friedrichs des Groβen in Sanssouci (1850-52). This depicts Frederick the Great playing the flute with a small ensemble and aristocratic audience. It takes place in a grand setting. At night with candles galore as illumination (expensive, if nothing else). It is incongruous. Those flax spinners will not be consuming high art at this hour, for sure.

The industrial revolution and the ruling (plutocratic) elite play their distinct roles in the journey to the current climate crisis. Images of trees being cut down are visual reminders of how the natural environment is the source of all exploitable resources. Constant Troyon’s painting Holzfäller (1865, Woodcutter) is a great illustration of this. Though I am sure this is not the actual meaning of the painting. Trees were, of course, felled well before the arrival of the industrial revolution for shelter, housing and agriculture. What is significant is how the deployment of technology turned it into a truly industrial process. Watch how trees are harvested in modern times as though they are bowling pins, to understand how the pace of destruction has increased.

There is one other theme here, to share. And that is “otherness”. Mihály Munkácsy’s 1873 painting Zigeunerlager (Gypsy Camp, right) expresses it well and nicely contrasts with Menzel’s Woodcutter (I note and am aware that both Zigeuner and Gypsy are pejorative terms. The Nazis, we remember, committed genocide against this group. Hence the word Zigeunerlager is particularly troubling. The correct term is Der Roma). That very same landscape lost to the axe is potentially a place of refuge for nomadic people. These are people who are seen as being rootless (and stateless), where in actual fact probably the opposite is true.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment