Archive for the ‘David Hockney’ Tag

David Hockney, Paris, August 2025

Eurostar from London, dinner, nearby hotel, sleep and then work out how to get to the Fondation Louis Vuitton building that, due to my lack of preparation, turns out to be a Frank Gehry building (left). It sits in a bizarre park that is home to a retro amusement park, amongst other things. Over breakfast we decided to walk – Google maps advised nearly 2 hours, but such is Paris, walking is a delight. By chance we ended up meeting up with an electric bus shuttle from Arc de Triumph to the building – further than we thought. Anyway, the marketing for the exhibition is here.

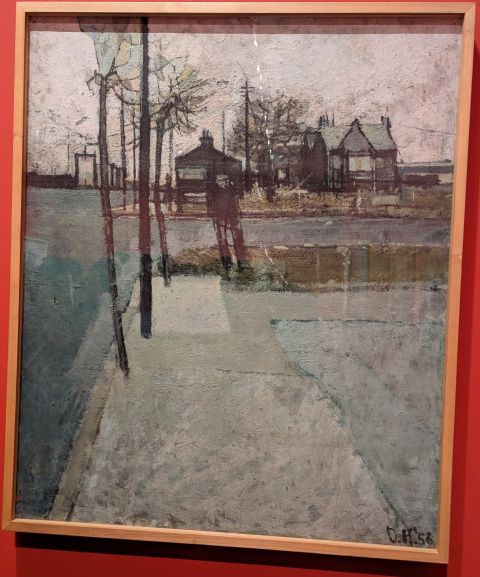

Once into the building we did as we were told and started in the first gallery. It was an exhibition that was organised chronologically by date. So Hockney’s earliest works can be found in that gallery, including the portrait of his father, life in what is now Greater Manchester (right) and series of abstract paintings exploring his early understanding of his sexuality. Then in 1964 he heads off to California. This period delivered some of his most famous images, for example, the Bigger Splash and a series of other poolside paintings that are now beyond my price bracket. But I have to say, I found this rather boring, egotistical, even narcissistic.

Portraits

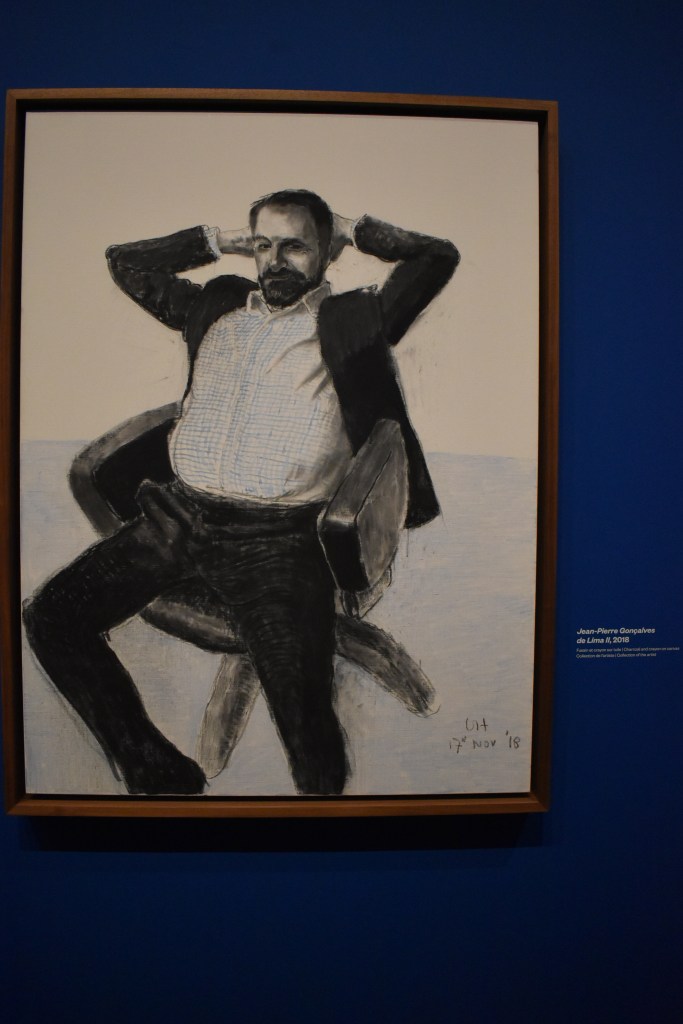

I like to think that artists have something to say (about the world) beyond themselves. Maybe the next gallery of portraits might reveal something, after all, the sitters were others, often pairs of others. There were lots of admirers of these portraits, but I felt that most lacked emotion. In fact, the only picture (actually a set of four) that showed emotion were a man towards his dog. All others seemed inert. I found one image that summed up this whole gallery (below right).

East Yorkshire

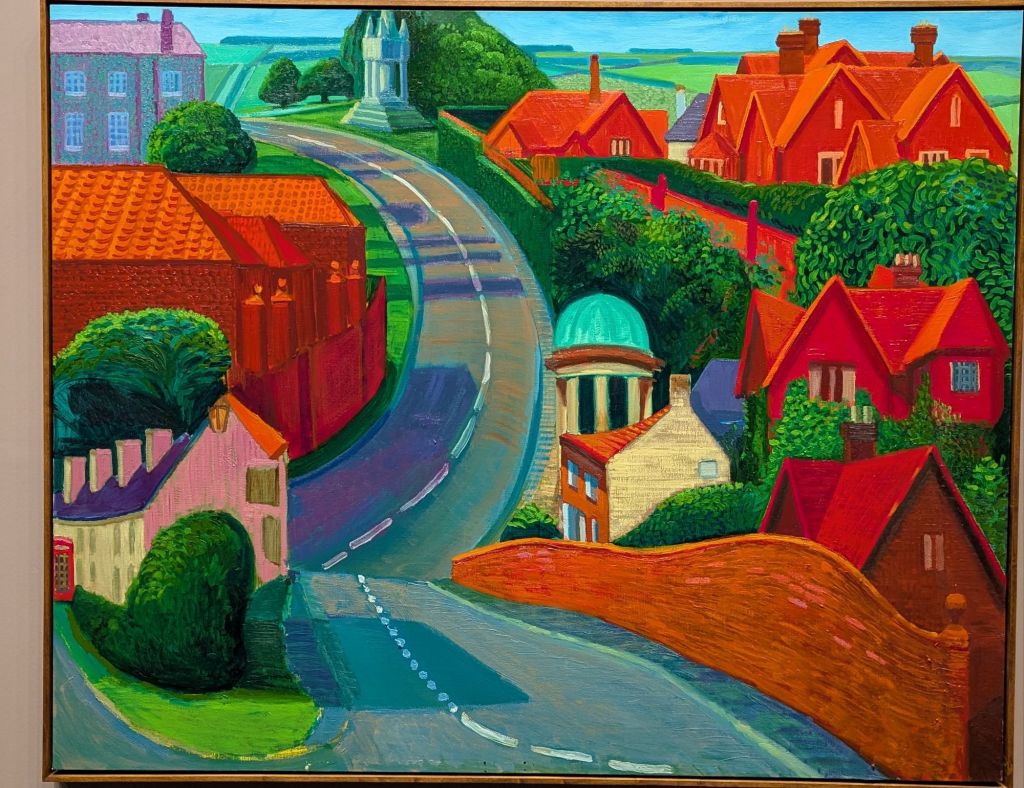

Onwards – Hockney came back to the UK and moved into his deceased grandmother’s house in Bridlington, Yorkshire. In this period he produced a significant number of landscapes depicting changing seasons; for example, a spot on a farm track. Man, easel, paints, brushes. Some of the pictures are huge, made up of 40 or so panels that oddly do not quite match or line up with one another. And they all seem to be without people or, indeed, animals. I can cope without people in the countryside. But not an absence of animals.

That was enough, time for coffee. We left the building in order to find refreshments – the gallery itself has an expensive restaurant but no coffee shop from what we could see. The park has a number of delightful outlets, so no problem.

The full artist

We were back within the hour to a gallery on the second floor which, frankly, we should have started in. This gallery showed what a consummate artist Hockney is and what he could have been had he wanted to be – but that is me being arrogant. I say this because Hockney himself writes on the entry panels that we might think that he has limited styles on which he can draw for his “periods” – all long-lived artists have those, I have come to realise. In this gallery were examples of Hockney aping the styles of other famous artists. There is always a nod to van Gogh, but we did not realise he was a fine cubist artist in the style of Picasso. I particularly enjoyed his take on Hogarth and the illusions generated in his picture, Kerby (After Hogarth) Useful Knowledge, 1975 (above left).

Then on to Munch and Blake (After Blake: Less is Known than People Think, 2023, left). This is the only image that alludes in any way to the welfare of the natural environment (the landscape gallery does not address any of our environmental challenges, indeed reproduces them with straightforward depictions of modern lowland farming). Blake’s painting was a representation of Dante’s Divine Comedy which, admittedly, I have never read. But here we have a holistic view of our human world – a dependence on the natural environment, the awe and fear of the galaxy and universe beyond, human history and a vulnerability (unclothed women holding up the globe) to the planetary system more generally. As we know, we have moved from the Holocene to the Anthropocene – our fate is in our hands, and we ignore the signals at our peril (increasingly decreasing temporality).

Theatre set drawing

And then there is the theatre work. Hockney was a great fan of opera and throughout his career he has been painting backdrops for some of the great opera houses worldwide. For this exhibition his work is immersive. One enters a large gallery to observe the paintings projected onto walls, with some being animated and involving motion. They are terrific. Another important aspect is Hockney’s experimentation. For example, he has created intriguing electronic pictures that track his method for drawing and painting, particularly landscapes. All credit to him for this. I spent quite a bit of time over these images.

Photo drawing

More recently Hockney has explored “photo drawing” (right – one of a series depicting the same “event from different angles). Equally in this almost recursiveness is his image of himself looking at his own pictures with subtle references to his own brilliance, such as the edition of “die Welt” underneath the small table (below left). And these, for me, sum it all up. Whilst I concede that Hockney is a versatile artist, able to work in most styles and genres and has a body of work that can fill the Fondation Louis Vuitton building in Paris. He is also just a shade too narcissistic for me really to embrace.

Exhibition ran from 9 April – 1 September 2025

One Gallery, climate messages

I recently went to Tate Britain in London. The gallery is home to many of my “friends” – a strange idea, but I always relax when I see the images in the flesh, as it were. In recent times, however, I have visited galleries with very different intentions. I want to know how – and if – art delivers a climate message, either by chronicling environmental decline or in championing its salvation. Both are true, of course.

On this visit, March 2023, I set myself the challenge of cataloguing one gallery (one gallery and bit, to be honest) for its climate message. Here is what I found.

Of course, LS Lowry has a story to tell. I always remember Brian and Michael’s song, Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs (no women for some reason). I even bought that record. But revisiting Industrial Landscape (left) I noticed other things in the picture not seen before (that is the beauty of art, there is always something new in the familiar to see. There are not too many people in this image – a few in front of the houses and along the central street leading to the factories. I see the trains on the viaduct and the barges on the aqueduct (if I see it correctly). What was new was the colour of the chimney emissions. They are not just sooty, they are toxic red, particularly those in the background. I wonder!

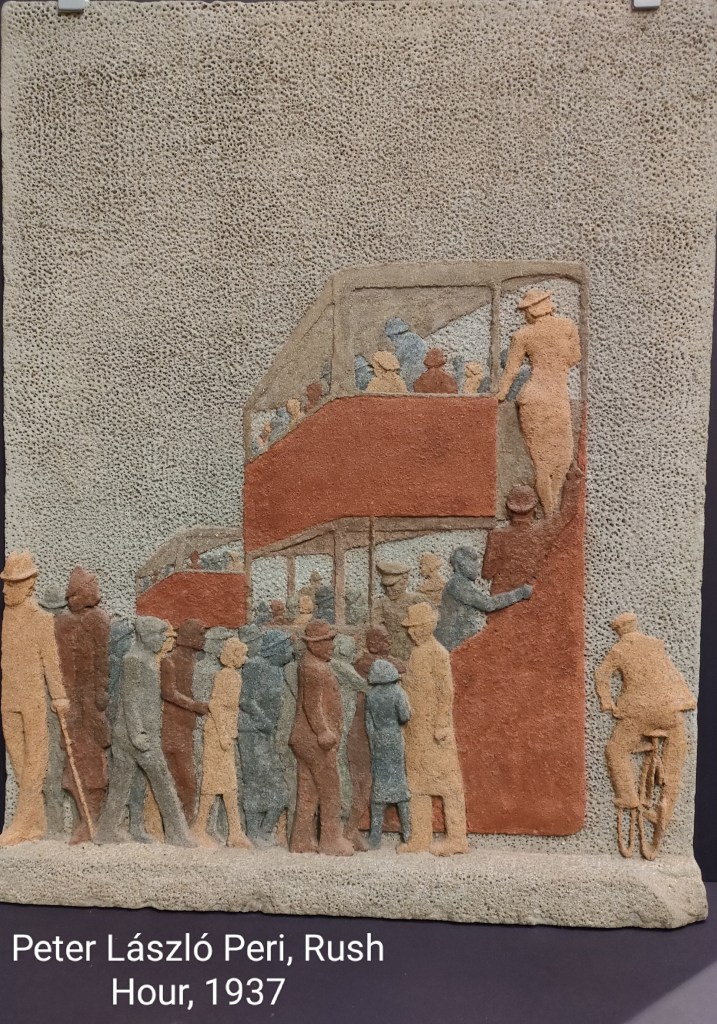

Slightly earlier (1937) the work of Peter László Peri. Peri does not paint, he uses stone to represent urban life. His rush hour incorporates one of my favourite images, that of the double-decker London bus. The image is effectively carved from a block of stone coloured in a rudimentary way; for example, copper red and earth brown. It is orderly and very English. On the one hand it looks like a depiction of the daily drudge of travel to-and-from work. But Peri sought to represent positively industrial society, so perhaps the woman climbing to the top deck of the bus represents progressive views about woman and work? There is also the cyclist taking on the diesel bus and wider traffic.

It is perhaps not surprising that Peri chose stone – he had been a apprenticed brick layer as well as a student of architecture in his birth city of Budapest, Hungary. Moreover, he was associated with the Constructivist movement dedicated to representing modern industrial society formed in Germany in 1915.

Peri arrived in England in 1933 – he was not in any way popular with the Nazis being both Jewish and a Communist.

Cliffe Rowe’s picture, Street Scene (left) depicts a pram (presumably for the health benefit of the baby inside) outside a terraced house. There is a woman sat of the step knitting (oddly revealing her underwear) and a man in shorts reading a newspaper. How typical this was, I do not know, but it seems to be a scene of aspiration. There is street lighting. Net curtains. In 1930, Rowe travelled to the Soviet Union and stayed for 18 months. He was impressed with the Soviets’ use of art to support the working class struggle; though he may have been taken in simply by propaganda. That said, on his return to England he became a founder member of the Artists’ International Association (along with Peri) which used art to oppose fascism.

Predating both of these artists was Winnifred Knights. Her picture The Deluge (1920, right) has a very contemporary interpretation. Men and woman either flee or resist rising water in a representation of the Biblical flood in Genesis. Clearly a contemporary interpretation – or translation – is climate change and rising sea levels. Not an act of God, but an act of humanity against itself (and all other inhabitants of the planet).

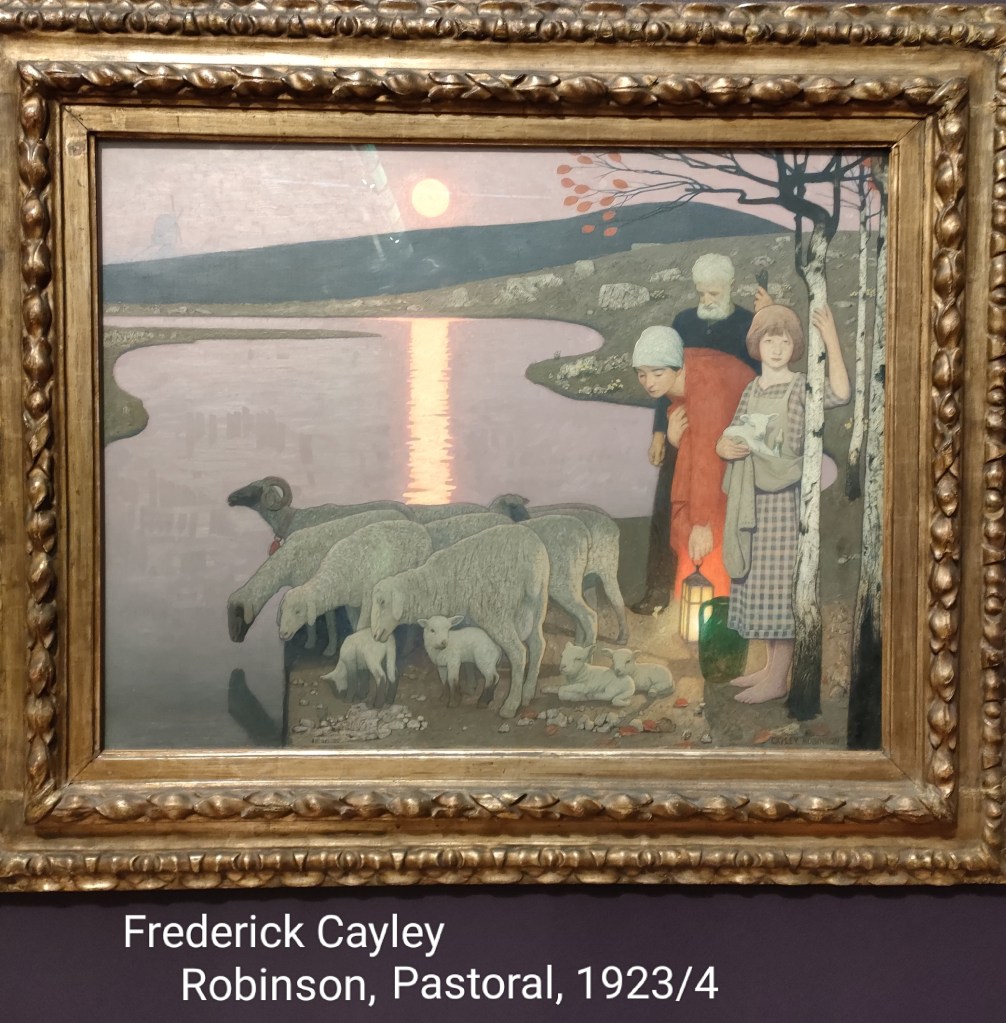

To see what we forfeit in the industrialisation of economies, we can draw on some of the more conservative images of the period. Frederick Cayley Robinson’s Pastoral (left) is a good example from the gallery. It depicts a family and a flock of sheep by the waterside. A child holds a lamb as a symbol of rebirth. It is rural idyll in the post WWI world. It is rural, but not idyllic. There is only a windmill as a concession to technology – enough to enable this simple life. Of course, it is not where we ended up.

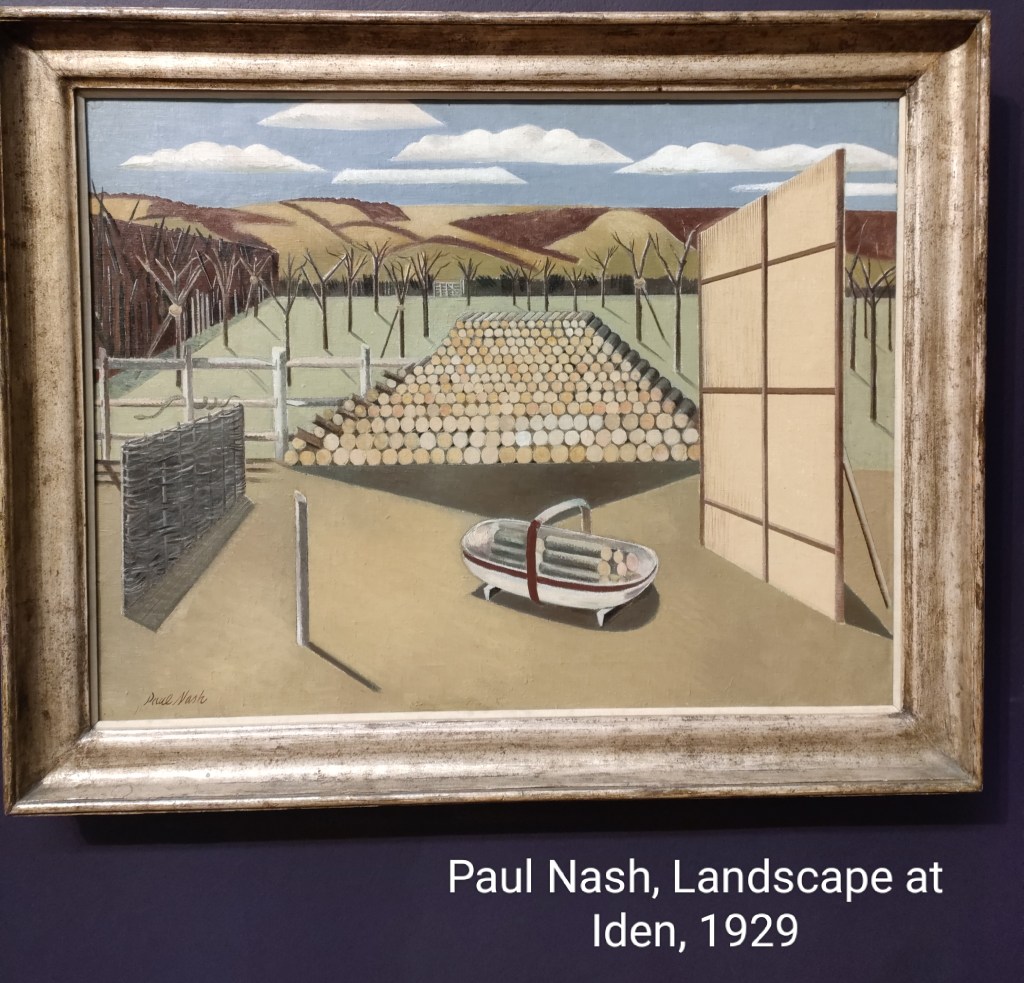

My penultimate choice is work by probably my favourite artist, Paul Nash. Nash was greatly affected by his experience of WWI. On my visit for the first time I saw Landscape at Iden (1929). His geometric shapes “blend” with the landscape, and in this case with felled trees. The felled trees are interpreted to mean lost souls in the war. The snake on the fence is easy to miss. It can represent evil, for sure (it was a serpent that tempted Eve to eat the apple), but pharmacies use the symbol of the serpent to represent healing. In Nash’s work it could go either or both ways, I sense. Whatever they are meant to represent, war, through history, has impacted on the natural environment. Despoiling it with armaments, clearings and extraction. I have not entirely convinced myself that this picture is translatable, but his pictures always leave me feeling understood.

I’m going to take a liberty with my next choice – reinterpreting a living artist, David Hockney. His picture The Bigger Splash (1967) is a representation of the water’s response to a dive into a pool. I have always seen Hockney’s California period as a reflection of unreality (Hockney admits his splash is not realistic) – the good life that comes from industrial society that is endured by others, particularly in the industrial Eastern USA. I feel vindicated inasmuch as when Hockney returned to the UK he bought a house close to where I was brought up in East Yorkshire. Those images are most certainly about the land, its plants and change.

Comments (1)

Comments (1)