Cigarette Advertising

My blog used to be dominated by the Germans’ willingness to advertise products that are deadly, when most other countries had banned the advertising of cigarettes. But for many years I photographed what I saw on the streets and wrote a short derogatory commentary on the stupidity. There were many campaigns for all the major brands. One of my favourites was Gauloises’ Vivre le Moment (examples left and below right). You simply had to because the product will kill you. Take the moment, for sure.

Fewer readers come to my blog since the ending of cigarette advertising. I have not found a replacement topic that so attracts (admittedly I have not been trying too hard). But my recording of billboards was only for a short time. The history of these images and the campaigns behind them goes back much further. Every now-and-again someone puts together a portfolio of historical images that are compelling. And so it was yesterday in the Guardian newspaper under the heading: Shock of the old: 11 vintage, vaginal and downright dangerous cigarette ads.

Incidentally, the Germans still do things that are not allowed in other countries. The most shocking remains driving down the motorway at absurd speeds in cars that should not be on public roads.

Rome 2023 – EUR’s modernism and a cemetery

EUR was Mussolini’s attempt in Rome at building a (new) Rome at scale using 20th century materials and techniques. And by goodness, the results are impressive. The neighbourhood is reached on Line B of the metro system. The Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (left) is visible directly from the metro station, EUR Magliana. It is as striking as anything in the old city. It stands in a fenced-off space with very little in the way of greenery. Like much of Rome, wildlife does not easily cohabit the space with humans. Feral cats do – also not good for birds and small mammals. Unfortunately the building is not open to visitors. Through the entrance door, one can see a big Fendi sign which suggests how the building’s purpose may have changed.

Don’t stop there, though. The wide avenues are themselves of interest and contrast. The coffee is a good price, too. The owner of such a businesses gave some advice as to where else we should go.

EUR is very much an administrative centre with at least two major offices of state parked there. The Finance Department has a fantastic frieze outside….fantastic in the sense of how it sends a shiver down the spine – Mussolini is depicted as being Mussolini on it. (lRight – first line on a horse).

Mussolini’s legacy is everywhere to be seen in this part of Rome. As much as that of Trajan and Augustus and Nero in the old city.

In the nearby “English” cemetery (Cemitero Acattolico – accessible from Pyramide Metro station) lies one of Mussolini’s greatest critics, and paid the ultimate price for it. Antonio Gramsci resided on the absolute opposite of Mussolini’s vision. Mussolini imprisoned him. And it was in prison where he died after 13 years’ incarceration. But those years were spent writing his so-called notebooks. I read a lot of Gramsci when I was a student of politics (my first degree) and to find his grave was extraordinary. No plan here, but it is what comes from random conversations with unexpected café owners in Mussolini’s new city.

Who else is in this cemetery? Well, Keats is (and his long-term friend, Joseph Severn). He went to Rome to get well (undoubtedly a better climate, but succumbed nonetheless). His tombstone bears the words “HERE LIES ONE WHOSE NAME WAS WRIT IN WATER”. This can be read in a number of ways – fleeting, ripples (when a pebble is thrown into it). He was a poet after all. You’ll find Percy Shelley there, too. What is important though is the tranquility of the space. Whilst it is notionally free to enter, a donation of 5 Euros is advised.

Rome December 2023 – Arrival and first day

26 December 2023: Once again we decided to spend the festive period away from home. Last year it was Naples, this year Rome. Whilst we do not need heat, a bit of less-cold is welcome. And maybe a little sunshine. Getting there by train is pretty straightforward. Munich-Bologna-Rome. I mention Naples because there is an interesting contrast. Many Neapolitans are on the streets on Christmas Day. Romans are not. Having arrived at Roma Termini last night, we found the Metro closed. The taxi queue was extended. We walked successfully for 30 mins to our hotel. But eat before you travel away from Termini as eateries are mostly closed.

We have been to Rome before. The Colosseum still stands and today it was heaving. As was the Pantheon. Long queues for both. But one of the significant beauties of Rome is the free culture available. Most churches are open. All have something interesting to share.

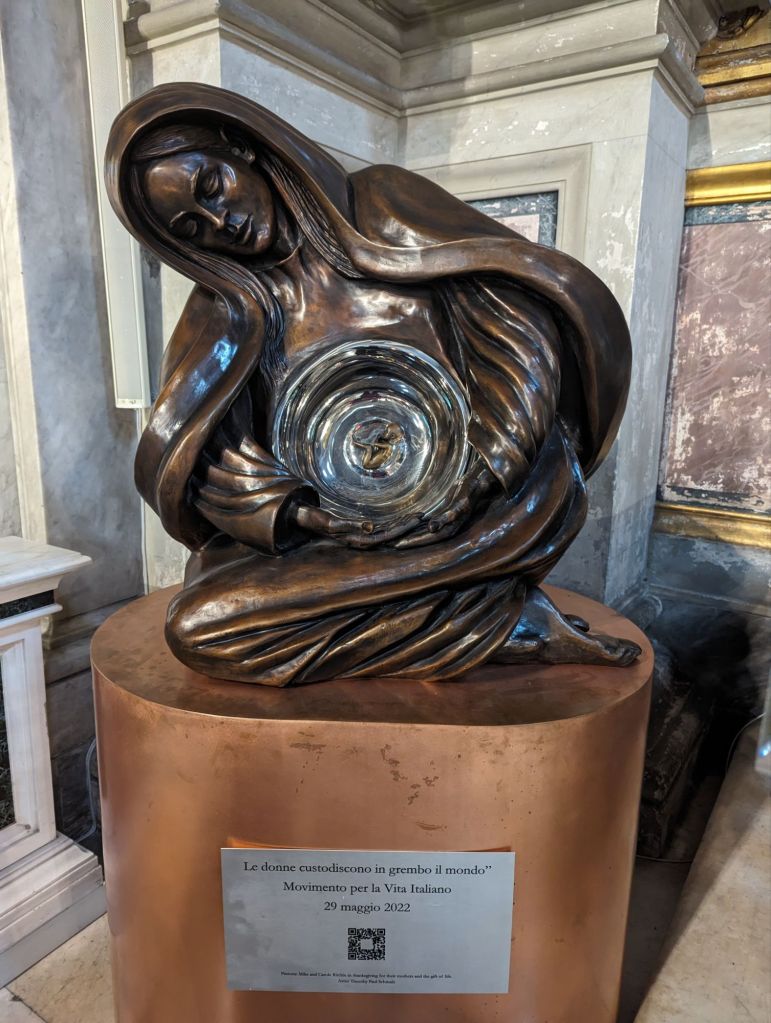

For example, the Church of San Marcello al Corso has recently commissioned some new art work. “Mothers and their Gift of Life” (right) is disconcerting. It is bronze and sculpted by Timothy Paul Schmalz. The woman in question may be Mary, but could be any woman with a baby growing inside her. This one is small (but aren’t they all?). But it is in a dish. I don’t know how to interpret that, but I read it as need and hunger, not the gift of life per se. Very odd.

If there was a theme linking my thinking today, it probably is the depiction of women. Whilst the mother is young and beautiful, there are some grotesques depicted on every building if one just looks up. The example (left) adorns the Palazzo della Consulta opposite the robust statues found in the Piazza del Quirinale.

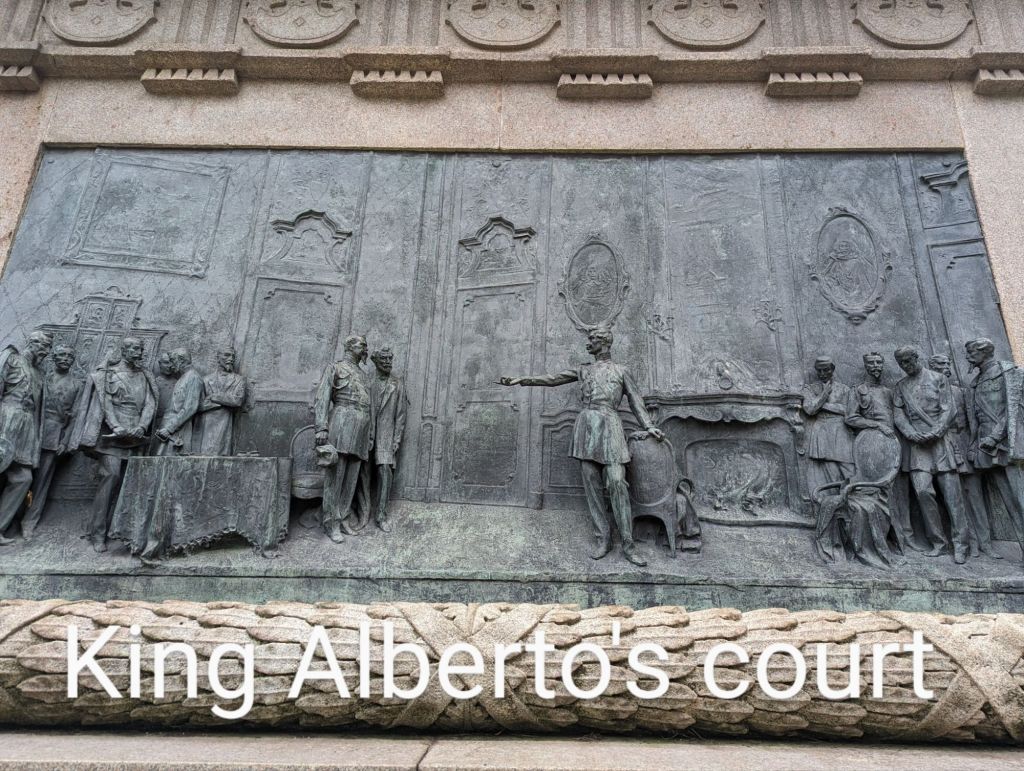

A little along from there is an unassuming garden (Villa Carlo Alberto al Quirinale). There is a monster statue of King Carlo on his horse, but the sculptures on the plinth are really interesting (right). It is the court of Carlo and, of course, it is exclusively men. If one looks carefully, the women are depicted only as pictures on the wall! On the other side is a lot of men dying in battle. There is a lot of that in Rome. Men dying in battle.

Michael O’Leary is right and very wrong, mischievously so

Michael O’Leary (left) is the boss of RyanAir. He has spent much of his life at the helm and took it from limping Irish airline to Europe’s biggest. As he says himself, RyanAir was early into the low cost business after the skies were deregulated and have kept the advantage over rivals. He’s fabulously wealthy off the back of that success.

So, on 26 December 2023 O’Leary proclaims that there is not enough used cooking oil in the world to fuel the world’s airlines for one day, let alone a year. on that he is right. But he has made many other claims that are not defendable with even a cursory analysis. Let’s take them one by one.

O’Leary argues that air travel contributes just 2pc of carbon dioxide. Ships contribute 5pc, but no-one is shouting about global supply chains. Here are 10 points to consider.

- We do not measure greenhouse gases as a percentage, we measure in absolute terms. That 2pc is equivalent to 800 Mt CO2 per year. If we are to get anywhere near even 2 degrees of warming (let alone 1.5 degrees), all GHGs have to be eliminated, Even a fraction of 1pc is too much. In meeting the 1.5 degree Celsius target, the atmosphere can absorb, calculated from the beginning of 2020, no more than 400 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2. Annual emissions of CO2 are estimated to be 42.2 Gt per year, the equivalent of 1,337 tonnes per second (https://www.mcc-berlin.net/en/research/co2-budget.html). At this rate, at the time of writing, we have 23 years before that budget is used up at current levels, but we have seen clearly how projections are changing – climate change is happening faster than expected. The models are being revised. And we continue to grow demand for fossil fuels whilst destroying carbon sinks such as oceans, forests, bogs, etc. For something most of us do not need, flying is disproportionately expensive in terms of carbon budgets.

- Whilst O’Leary might say that 2pc is not much, carbon emissions overall have doubled since the mid-1980s. Aviation has just kept up with the average increase in emissions across the board. Absolute emissions from aviation are increasing.

- Carbon generated by aeroplanes is not the same as that emitted by land-based activities. Indeed, if we consider aviation’s full impact it is more like 3.5pc. Aviation emits other greenhouse gases, and the release of water vapour at altitude significantly increases its warming impact. Accounting for this, its contribution increases by around 70%.

- CO2 emissions arising from aviation are not globally fair (equitable). It is the relatively rich who fly. 1 per cent emit half of GHG emission from aviation. Business class is more carbon intensive than economy. Private jets…let’s not go there. Most people on the planet have never flown (estimated between 80 to 90pc) and have not contributed to aviation-generated carbon emissions. Put another way, only 5pc of people fly in any one year (less than that for international travel). The average air traveller takes just over 5 flights per year (1).

- We do not adequately count all emissions. Domestic flights are ok – they are factored into national emission-counting, but international/long haul belong to no one (though airlines to count them). Incentives are not in place to reduce emissions from long-haul flights. This we must get to grips with, but recent stunts like those from Branson do not help.

- O’Leary seeks to distract attention – forget aviation, much better and easier to electrify cars and vehicles. Vehicular emissions are 20pc of the total with cars alone producing 3bn Mt CO2e annually. Another diversion – Air Traffic Control – if they could be more efficient there would be no need to spend hours circuling airports in stacks (the fact that there may be too many planes in the air is not considered).

- There is the technological fix – O’Leary has them all up his sleave. Seemingly he is “generally a believer that technology and human ingenuity will overcome climate change”. He goes on “I have no doubt that we will not decarbonise because we tax people more” So belief will get us there; though at this point in time, there are no viable electric planes in sight. Or any other fuels, for that matter.

- O’Leary argues that “[p]eople will absolutely not stop flying because of concerns about climate change”. This may, of course be true, but that is why we have Governments, regulations and tax to provide the incentives. What O’Leary is doing at RyanAir is expand capacity with the purchase of new fuel-efficienter aircraft. But they are not sustainable.

- So. let us look at the low cost base and the subsidies airlines get to maintain them. Fuel (tax) is a huge subsidy not open to land-based services. Some old data – but in 2012 the lack of tax on fuel amounted to an annual subsidy of £5.7bn. No VAT on tickets add 4bn to the total. In the UK, the Government actually reduced air passenger duty on domestic flights. Seemingly there is another £200m subsidy to the industry. And then there is the infrastructure provided by the state such as roads and rail links. Did Heathrow really need a fourth rail link to the airport with CrossRail?

- And on ships, there is a lot of discussion both amongst engineers, campaigners and industry about decarbonisation. Try these:

Pictures:

Michael O’Leary, World Travel & Tourism Council

RyanAir Boeing 737, By Dylaaann – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114958876

References:

(1) Stefan Gössling, Andreas Humpe, The global scale, distribution and growth of aviation: Implications for climate change, Global Environmental Change, Volume 65, 2020;

Holidaying in the UK, 2023

Well, this year, we decided to keep our holiday simple – UK, one location for accommodation and lots of train options. Yes, of course, the West Country. We drove to Plymouth, coming off at the Devon Expressway to stay at the IBIS Hotel (more of a motel, really). From there buses to Plymouth and from there trains to St Ives, Newquay and Torbay. All good. We used the van only to get to Dartmoor for a couple of walks.

Our first day, naturally, was in Plymouth. It is years since I have been there. Short of remembering Plymouth Hoe, it was a new place. And whilst it is nice to walk around the bay, observe its great breakwater, marvel at the Tinside Lido and raid the tourist information office, there are three highlights. A day at the Box – the city’s museum and art gallery, the Guildhall (not actively open to the public, but certainly allowed) and food.

The Box is everything a municipal museum should be. It is full of the place’s history – however (in)auspicious it may be. Plymouth certainly celebrates Napoleon’s capture and exile to St Helena as he was quite a tourist attraction when he landed. Immediately inside the box the grand figures that guided the town’s ships now hang from the ceiling (above left). It also has temporary displays in its magnificent galleries. We enjoyed very much a display of work by (Sir) Joshua Reynolds, a locally-born portrait painter of the rich. The I’m no expert, but the pictures a fine works, at scale and full of questions that artists pose because they can. One big question is around the identity of the black woman in his picture of Lady Elizabeth Keppel (painted somewhere around 1762, right, after at least two live sittings compared with Keppel’s eight). The question is asked for two reasons, first, she is not named, but second, she is depicted not as an equal, but neither as an absolute subordinate. Her clothes and jewellery may have been donated by the family, but that in itself is significant such that she can be represented as a woman of status, albeit as a maid servant. The likelihood of Reynolds seeking to represent a black woman as one with status is not high, but it is one of the quirks of art that inadvertently demonstrate more than perhaps intended.

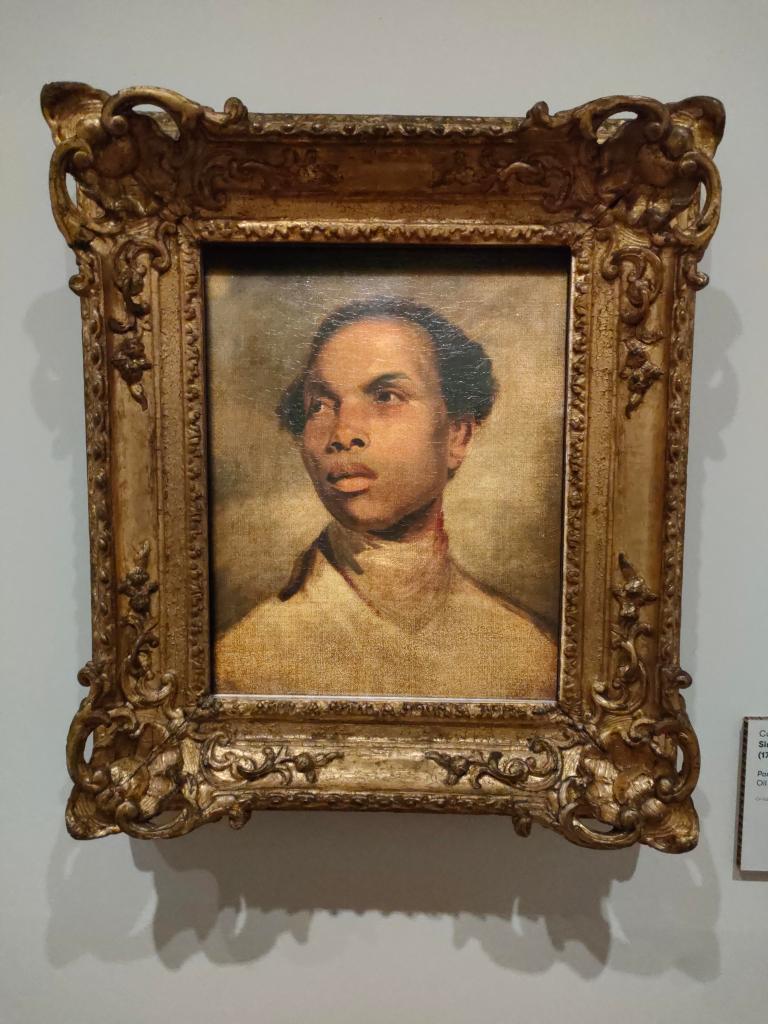

Maybe I do Reynolds a disservice as there is another picture in the collection (left) of a black man – just his portrait; he too, is depicted as a noble. He could have been Samuel Johnson’s servant, Francis Barber (originally named Quashey), born in Jamaica and came to England as a valet. He may have assisted Johnson in his dictionary. What is clear, he became Johnson’s heir. He could also have been Reynolds’ own servant (footman), is written about in his memoirs (without actually naming him).

The museum’s permanent collection includes some fabulous ceramics, some of which are nearly 400 years’ old from China – at the time when the porcelain was a unique Chinese export. A first glance the pot (right) is rather dull, but the “double gourd” has a form that is one of the most ancient of Chinese ceramic shapes (undated, unfortunately). The colour jade was seemingly extremely difficult to achieve!

Also, Barbara Hepworth’s work gets a look in. Three paintings (Opposing forms, 1970; Autumn Shadow,1969 and Oblique Forms, 1969) are on display, probably just to point to the people at St Ives, where she lived and worked, they do not have exclusivity. Though with Hepworth, there are many public examples, not least the work, Winged Figure (1963), adorning the side of the John Lewis shop on Oxford Street, London.

The Guildhall is for fans of 20th Century Guildhalls or – what I prefer to see them as – public spaces for citizens to attend functions, exhibitions, entertainment, etc. The main hall in the Guildhall has it all – height, a painted ceiling, natural light, a stage, an upper circle. We stumbled into it and the caretaker was delighted to share his own knowledge of the place, open the curtains, put on the lights and leave us to it, basically.

Finally food. I sense there is a single place for vegetarians to consider eating in Plymouth – though happy to be corrected). That place is Cosmic Kitchen, run by twin sisters, Gabriela and Lucia Evangelou, serving Mediterranean-style food, including their vegan moussaka and a regular specials board. The venue is worth a visit in itself (old chapel) and at the weekend it doubles up as a club (for younger people than us, I predict).

One Gallery, climate messages

I recently went to Tate Britain in London. The gallery is home to many of my “friends” – a strange idea, but I always relax when I see the images in the flesh, as it were. In recent times, however, I have visited galleries with very different intentions. I want to know how – and if – art delivers a climate message, either by chronicling environmental decline or in championing its salvation. Both are true, of course.

On this visit, March 2023, I set myself the challenge of cataloguing one gallery (one gallery and bit, to be honest) for its climate message. Here is what I found.

Of course, LS Lowry has a story to tell. I always remember Brian and Michael’s song, Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs (no women for some reason). I even bought that record. But revisiting Industrial Landscape (left) I noticed other things in the picture not seen before (that is the beauty of art, there is always something new in the familiar to see. There are not too many people in this image – a few in front of the houses and along the central street leading to the factories. I see the trains on the viaduct and the barges on the aqueduct (if I see it correctly). What was new was the colour of the chimney emissions. They are not just sooty, they are toxic red, particularly those in the background. I wonder!

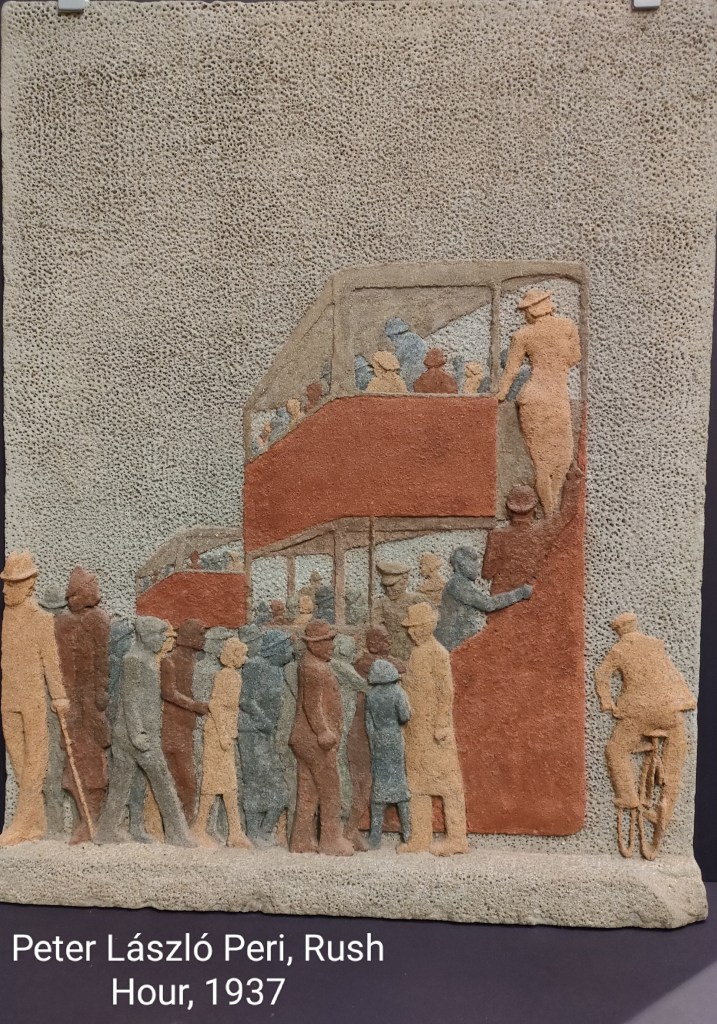

Slightly earlier (1937) the work of Peter László Peri. Peri does not paint, he uses stone to represent urban life. His rush hour incorporates one of my favourite images, that of the double-decker London bus. The image is effectively carved from a block of stone coloured in a rudimentary way; for example, copper red and earth brown. It is orderly and very English. On the one hand it looks like a depiction of the daily drudge of travel to-and-from work. But Peri sought to represent positively industrial society, so perhaps the woman climbing to the top deck of the bus represents progressive views about woman and work? There is also the cyclist taking on the diesel bus and wider traffic.

It is perhaps not surprising that Peri chose stone – he had been a apprenticed brick layer as well as a student of architecture in his birth city of Budapest, Hungary. Moreover, he was associated with the Constructivist movement dedicated to representing modern industrial society formed in Germany in 1915.

Peri arrived in England in 1933 – he was not in any way popular with the Nazis being both Jewish and a Communist.

Cliffe Rowe’s picture, Street Scene (left) depicts a pram (presumably for the health benefit of the baby inside) outside a terraced house. There is a woman sat of the step knitting (oddly revealing her underwear) and a man in shorts reading a newspaper. How typical this was, I do not know, but it seems to be a scene of aspiration. There is street lighting. Net curtains. In 1930, Rowe travelled to the Soviet Union and stayed for 18 months. He was impressed with the Soviets’ use of art to support the working class struggle; though he may have been taken in simply by propaganda. That said, on his return to England he became a founder member of the Artists’ International Association (along with Peri) which used art to oppose fascism.

Predating both of these artists was Winnifred Knights. Her picture The Deluge (1920, right) has a very contemporary interpretation. Men and woman either flee or resist rising water in a representation of the Biblical flood in Genesis. Clearly a contemporary interpretation – or translation – is climate change and rising sea levels. Not an act of God, but an act of humanity against itself (and all other inhabitants of the planet).

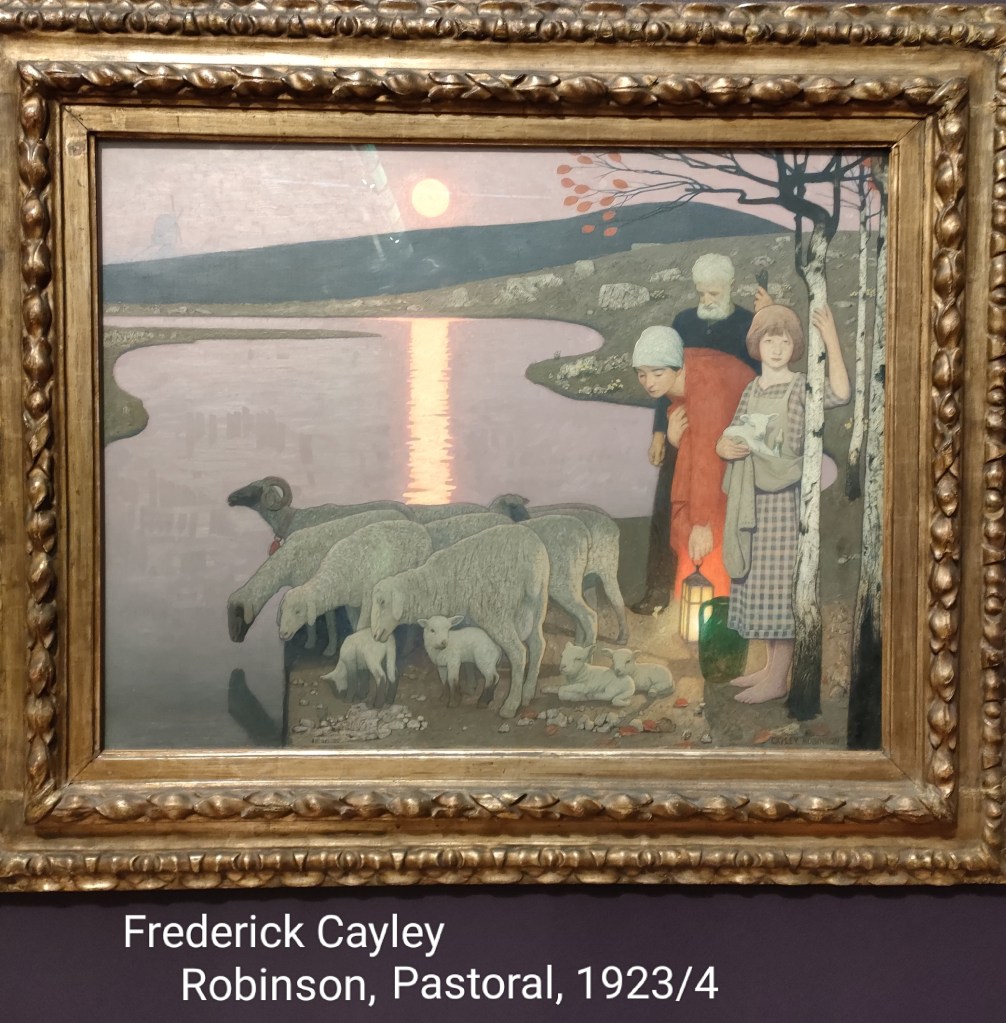

To see what we forfeit in the industrialisation of economies, we can draw on some of the more conservative images of the period. Frederick Cayley Robinson’s Pastoral (left) is a good example from the gallery. It depicts a family and a flock of sheep by the waterside. A child holds a lamb as a symbol of rebirth. It is rural idyll in the post WWI world. It is rural, but not idyllic. There is only a windmill as a concession to technology – enough to enable this simple life. Of course, it is not where we ended up.

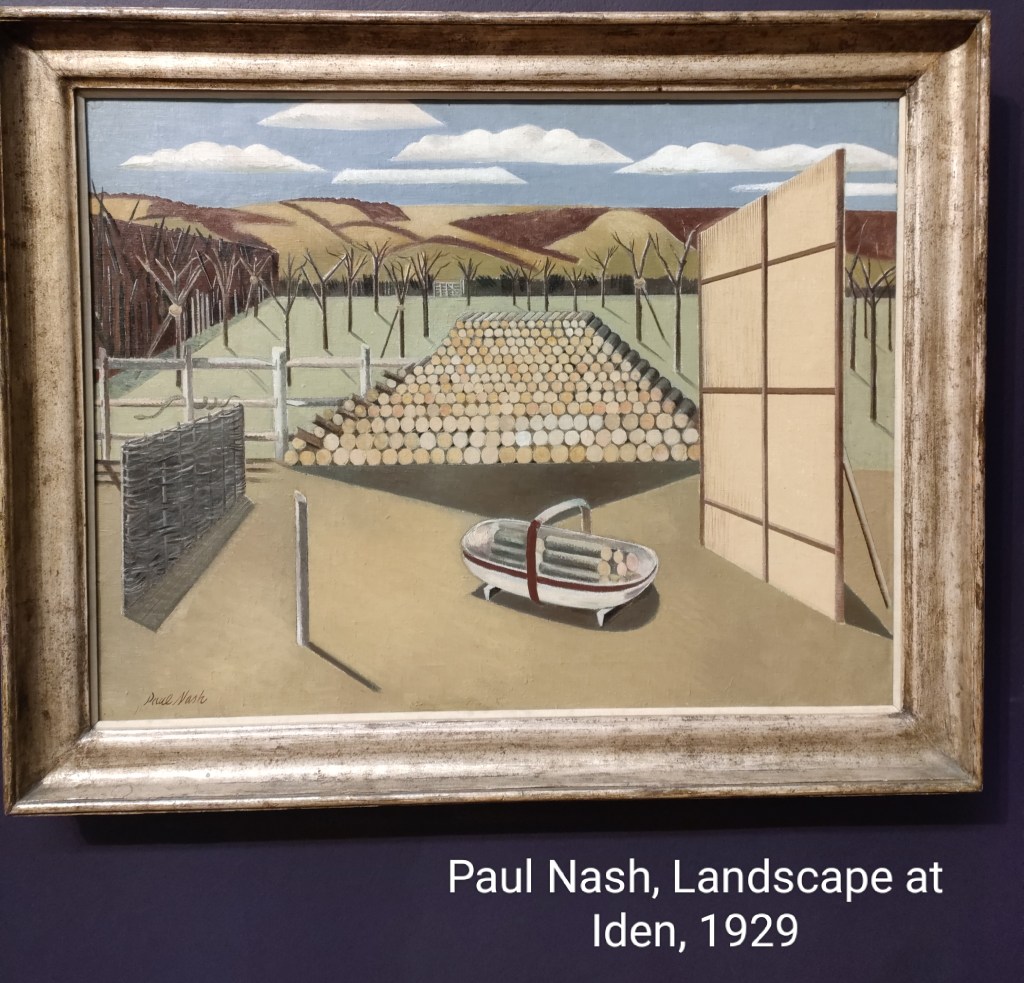

My penultimate choice is work by probably my favourite artist, Paul Nash. Nash was greatly affected by his experience of WWI. On my visit for the first time I saw Landscape at Iden (1929). His geometric shapes “blend” with the landscape, and in this case with felled trees. The felled trees are interpreted to mean lost souls in the war. The snake on the fence is easy to miss. It can represent evil, for sure (it was a serpent that tempted Eve to eat the apple), but pharmacies use the symbol of the serpent to represent healing. In Nash’s work it could go either or both ways, I sense. Whatever they are meant to represent, war, through history, has impacted on the natural environment. Despoiling it with armaments, clearings and extraction. I have not entirely convinced myself that this picture is translatable, but his pictures always leave me feeling understood.

I’m going to take a liberty with my next choice – reinterpreting a living artist, David Hockney. His picture The Bigger Splash (1967) is a representation of the water’s response to a dive into a pool. I have always seen Hockney’s California period as a reflection of unreality (Hockney admits his splash is not realistic) – the good life that comes from industrial society that is endured by others, particularly in the industrial Eastern USA. I feel vindicated inasmuch as when Hockney returned to the UK he bought a house close to where I was brought up in East Yorkshire. Those images are most certainly about the land, its plants and change.

Pompeii and Amalfi Coast – Festive period 2022/23

The obvious out-of-Naples places to visit are Pompeii/Vesuvius and the Amalfi Coast. Pompeii we self-organised. We took at train from Naples Central towards Salerno and a short shuttle bus to the Pompeii excavation from Pompeii railways station. All very straightforward. The Pompeii site closes about 1700 at this time of the year, so there was a bit of a rush to the train back to Naples. In the summer I suspect it is a bit of a crush.

The second – Amalfi Coast – we subcontracted out to a company called Tramvia. Tickets are sold from the many street kiosks. They pick up in the morning on a big coach from around the town and then separate passengers by tour at a spot on the edge of the city. We ended up in a transit van (with seats, obviously) with a driver who shocked many of us with his clifftop hustling and adventurous overtaking. In the dark. We were first dropped off at Positano (right). We had a couple of hours to walk down to the beach, get coffee, visit the church and wander through some of the many pottery shops. Enough time.

And then on to Amalfi itself. Another two hours sufficient for a bit of wandering along alleys in search of an entrance to the so-called cathedral (left) which we did not find – the entrance, that is. We settled for a glass of wine and a light snack. Suffice to say, the driver wasted no time getting back to Naples. We needed more wine to calm the nerves, or that is at least our excuse.

Pompeii…well, at least we controlled the getting there. We hired a guide (shared with a few others) who was good value. His Italian English was perfect. He sounded a bit like Francesco da Mosto, for those in know. And mischievous with it. We subsequently found out that some of the things he told us were not absolutely true; though it took the great Mary Beard to put him right. For example, the difference between slaves and slave owners was not as great as we were told. Beard tells us that many slaves won their freedom and became citizens of the city in their own right, though not if they did something that warranted a flogging. To be flogged is to be permanently labelled. Moreover, some slaves were highly educated and skilled by the standards of the time. The rich could have a slave doctor, for example. What was constant was food – rich and poor, slave and slave owner all ate much the same – seafood, grains and nuts.

Pompeii is a great experience. There is plenty of room and quiet areas, apart from the ever-popular brothel – which is not really worth visiting – there is more erotica on display in the Naples Archaeology Museum which we also checked out. There are a few lessons for all of us to take from Pompeii. Many people died because they did not know that Vesuvius was a volcano. And when they tried to flee, they hid. Knowledge is important; there was nowhere to hide from the ash. And those not prepared to forfeit their wealth, perished with it. Knowledge also was lacking in the plumbing. Whilst it was sophisticated in terms of capture of rainwater, piping and pressurizing, the lead pipes were also lethal (above right).

It is quite an extensive excavation – and ongoing (above left). The killer – Vesuvius – sits to the north. Pompeii itself used to sit directly on the shoreline, but the eruption essentially moved it backwards! The city is a great snapshot, too, in the developments in architecture. This bit of Italy is prone to earthquakes as well as volcanic activity. The Pompeiian – if that is who they are – architects learned how to strengthen their buildings – eventually adopting the diamond formation (right).

But ultimately the lives of the people before the eruption look just like our own: domestic, consumptive, with entertainment (albeit gladiators) and eating (restaurants/home).

And having written all of this, I suddenly read this in the Guardian under the headline ‘Astonishing’ Pompeii home of men freed from slavery reopens to public.

Naples – Festive season, 2022/3

The dread of winter, of course, prompts thoughts of being somewhere a little warmer for at least some of the colder time. We’ve been to Seville/Andalucia over this period before, but travelling by train there this time proved prohibitively expensive. Second best – though with hindsight unfairly so – was Naples.

We travelled on 25 December Euro City Munich to Padua (end station, Venice) and then TrenItalia Frecciarossa (high speed, right) to Napoli via Rom. It is a good day to travel – busy but not too busy. A cafe was open in Padua station (above left). The coffee was timely and great! Total journey time around 12 hours. One hour changing time in Padua. A bit of a delay in Rom. Dodgy power sockets on train.

We were staying in the Municipio district of Naples – three stops on Line 1 on the metro. There was a ticket kiosk in the passage between the main station and the metro station. It takes about ten minutes to walk between the two.

The first thing to say about Naples – and it has been said many times by many – it is busy. Crazily so. Be prepared for cars – and particularly motor scooters – to demand you get out of the way, even in streets (for want of a better word) that look like pedestrian walkways. They are not.

Eating is easy, even on 25 December. A local diner (right) was open adjacent to the hotel. There are many examples like this. Pizza, of course. Pasta and a mix of vegetables for those seeking vegetarian options, as we were.

In fact, we had many eating experiences. There are a couple of vegetarian options. Both good, one less friendly than the other. Friendly was Cavali Nostri (left). This place was not a concession to vegetarian food. Whoever runs it knows what is vegetarian food. So good the first time that we entrusted to them new year’s eve. We knew there was a special menu, but we had not quite digested the fact that there would be nine courses. Nine! And course 6 would be risotto – a meal in itself. Still, we got some of our new favourite vegetable, friarielli broccoli. Not really broccoli. More like tough and chewy spinach.

The other place was Un Sorriso Integrale Amico Bio. The menu was extensive and interesting. And it was quick. But we never felt truly welcome. The first time we went it was “full” – we could come back in an hour (by then 2130); the second time, we could come back, but we’d get ignored once the order was taken. And so it proved. It became a rather an inexpensive meal, in retrospect.

We had various other experiences in – and off – the main thoroughfares. All very similar. Pizzas are great. Service mixed. Prices very fair, including for wine. Mostly street food, including fried pizza, for which people were well prepared to queue quite some time to get. One of the odd things about pizzas is that many people cut off the crusts and leave them (along with other food items – food waste is a problem here, I sense).

There are many wonderful little bars for coffee and cake. Quite a lot are quirky, and not traditional in any way; for example, this place on the left – Posca-Bar Bakery Bistro – is located on Via Port ‘Alba close to the Dante Metro.

And so to the nine courses at Cavali Nostri:

Summer 2022: the €9 ticket holiday – 2

Art

Holidays often feature art – why would they not? In this journey we’ve been to Berlin, Elblᶏg and Dresden. The latter two are provincial cities with their own take on what should be shown and what not. And how.

Elblᶏg surprised me. The art is everywhere in the public realm. Seemingly in 1965 a number of artists were commissioned to make art and place it just about everywhere in the city. Examples of the work are below, but what it does to a place is interesting. In some cities the art would be defaced, damaged or vandalised. I saw none of this. 1965 – that’s 57 years! I assume that the art reflects the town and its people. Most of the artwork is made of steel, yet compelling. Maybe no one notices it, but it is there.

In Dresden, art has a very different role. Dresden celebrates its kings or “electors” The Residenz – effectively the palace of the elector August the Strong (apocryphally he can snap a horse shoe by his brute strength). He was strong, but probably not in this sense. His art collection – or treasures – illustrate just what constituted his ego. There is no question that most of the objects in the galleries are exquisite. I simply cannot imagine how most of them were decorated. Some of them were linked to what was probably 17th Century high technology such as clocks. The example on the left is a roll-ball clock. The ball is rock crystal and it rolls down the tower. It takes exactly one minute. Inside, seemingly, another ball is raised “emporgehoben” (whatever that is supposed to mean in reality) which moves on the minute hand. Saturn then strikes a bell, and twice a day the musicians raised their wind instruments and an organ played a melody. It is an extraordinary piece; but somehow I prefer time keeping to be a little simpler, at least in its reporting.

The jewels are one thing, the ivory is quite another. I have to say I’ve never seen so much carved ivory in one place. It is quite sickening. The carving is amazing, however. Take this frigate (right). I do not know how many elephants died for this piece, but everything apart from one feature is obscene. It dates from 1620 and bears the signature of Jacob Zeller. Of course the frigate is supported by the carved figure of Neptune. The sails are not ivory, nor the strings. But there 50 or so small human figures climbing those ropes. They are extraordinary.

There is an ivory clock to rival the jewelled example above. But quite the most sickening is to carve an elephant from ivory (left). There’s a receipt for its purchase in 1731. It is actually four perfume bottles hidden the castle turrets. What gets me particularly is the failure of the gallery to say anything about the exploitation of nature. These are simply curated as exquisite objects of great value.

It was not only elephants from the natural world that were exploited. Here is something I absolutely did not know, coral was a material for artists and treasures in this period. The bizarre figure on the right is seemingly a drinking vessel in the shape of the nymph Daphne who metamorphosised into a tree (coral) to escape Apollo’s “harassment”. It is not just one piece, there’s lots of it in this gallery. Not a word about how the coral was gathered and where from.

But there’s more. There are some deeply troubling figures of black people. I am not going to upload the photos of a sedan chair occupied by an ivory Venus and carried by “Hottentots”. Venus is attributed to court sculptor Balthasar Permoser (1738 or so) and the figures to court jeweller Gottfried Döring.

I left this gallery feeling troubled and dissatisfied with the curation. They must do better.

The Albertinum is another gallery in the historic centre of Dresden. There is some interesting stuff here. Sculpture is not usually my thing, but it has a number of examples of art that was deemed by the Nazis as “degenerate”. For example, Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s “Kneeling Woman” (1911, left) which is quite extraordinary, but obviously too extraordinary for the Nazis. Then oddly there is a piece by Barbara Hepworth, Ascending form Gloria, 1958). Odder still is a decorated wooden crate ascribed to Jean-Michel Basquiat (I am probably wrongly describing it). There are a couple of contrasting pieces by Tony Cragg – a wooden abstract sculpture and a cube made up of compressed rectangular objects ranging from lever-arch files to old VHS video players.

The upper floors are full of fine art. Again, keeping to the theme of degeneracy, climate and perhaps art that captures some of the potential consequences of unchecked warming, I start with Ernst Ludwig Kirschner’s Street Scene with Hairdresser Salon (Straβenbild vor dem Friseurladen, 1926). Kirschner was part of a group of artists known as the Brücke Group. Like many art movements the members were all against “old establishment forces” and following artistic rules. The bright colouring is an example. So shocking were the paintings that they could not be purchased by the City. Eventually, they became accepted and acceptable, only to find them labelled as degenerate in 1937.

What was not degenerate was Hermann Carmiencke’s Holsteiner Mühe (1836, Holstein Mill). I choose this because water was a natural source of sustainable motive power. The steam engine was arguably introduced to break the collective power of labour and because the water resource ultimately could not be shared by the direct owners of capital.

Finally from the Albertinum I selected Wilhelm Lachnit’s Der Tod von Dresden (1945, The Death of Dresden). It is, of course, a reflection on the human suffering arising from the second-world war. The climate crisis will bring its own deprivations and a fight for resources. We will see these times again, I fear.

A quick word on Dresden. The historic centre was essentially rebuilt from 1985. Many of the historic buildings were left as shells and rebuilt using plans and authentic materials. It was an exceptional achievement and good on the eye; the Semper Opera House, for example (above left). But this is not a city preparing for rising temperatures. Whilst there are green spaces, this central area is totally devoid of natural shade. The new centre around the railway station is largely concrete-based retail. Could be anywhere.

Meanwhile in Berlin, we visited the Nationalgalerie. I was taken by the work of Adolph Menzel. He obviously earned his money painting portraits of rich men, but he also had much to say about contemporary issues of the time – the mid 19th century. He is, by definition, a contemporary of Turner. And Menzel’s picture Die Berlin-Potsdamer Eisenbahn (1847) has some similarity to Turner’s Rain Steam and Speed which dates from 1844.

Menzel also painted a number of factory scenes – Flax Spinners, dangerous women’s work. The only safety equipment is clogs on their feet.

Contrast this image with that of his painting Flötenkonzert Friedrichs des Groβen in Sanssouci (1850-52). This depicts Frederick the Great playing the flute with a small ensemble and aristocratic audience. It takes place in a grand setting. At night with candles galore as illumination (expensive, if nothing else). It is incongruous. Those flax spinners will not be consuming high art at this hour, for sure.

The industrial revolution and the ruling (plutocratic) elite play their distinct roles in the journey to the current climate crisis. Images of trees being cut down are visual reminders of how the natural environment is the source of all exploitable resources. Constant Troyon’s painting Holzfäller (1865, Woodcutter) is a great illustration of this. Though I am sure this is not the actual meaning of the painting. Trees were, of course, felled well before the arrival of the industrial revolution for shelter, housing and agriculture. What is significant is how the deployment of technology turned it into a truly industrial process. Watch how trees are harvested in modern times as though they are bowling pins, to understand how the pace of destruction has increased.

There is one other theme here, to share. And that is “otherness”. Mihály Munkácsy’s 1873 painting Zigeunerlager (Gypsy Camp, right) expresses it well and nicely contrasts with Menzel’s Woodcutter (I note and am aware that both Zigeuner and Gypsy are pejorative terms. The Nazis, we remember, committed genocide against this group. Hence the word Zigeunerlager is particularly troubling. The correct term is Der Roma). That very same landscape lost to the axe is potentially a place of refuge for nomadic people. These are people who are seen as being rootless (and stateless), where in actual fact probably the opposite is true.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment