Archive for the ‘climate change’ Tag

Book Review: Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake

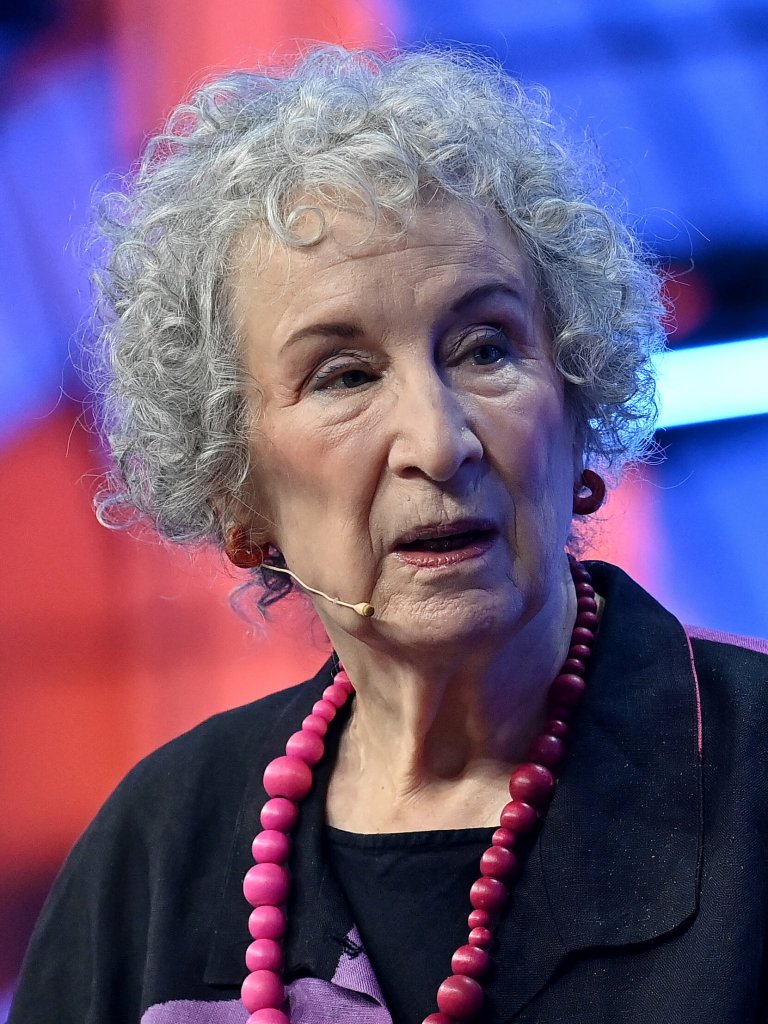

This is my first Margaret Atwood (left) experience. I was gripped. And I was taken somewhere not unfamiliar: a dystopian view of the future. Now bearing in mind this book predates Covid-19, it is quite chilling. Bearing in mind this predates Trump and tech billionaires, doubly so. One has to give her credit for what follows. Once again, please note, I am a novice literary critic and my review here has spoilers. This book is also the first part of a trilogy (the subsequent books are not reviewed).

The story is told through the experiences of two men, Crake and Jimmy. Only Jimmy exists before and after the thing that happens to humanity. Jimmy grows up in a family where his parents work for a corporation, HealthWyzer, that, essentially, makes organic life forms. For example, Happicuppa is coffee plants where the beans all ripen together so can be harvested by machines. However, foremost amongst the animal lifeforms are pigoons – pigs that grow organs for human transplant that can be harvested whilst the animals are still alive. Essentially reusable pigs. But there are many other hybrid-type creatures made by corporations: rakunks (make good pets), wolvogs (great guard creatures), spoatgiders (goat-spider – good for bullet-proof vests), rockulets (absorb water high humidity/let it out in low humidity), snats (snake-rats) and crakers (named after their creator) – humanoids that drop dead at 30, bear no malice, enjoy enhanced immune systems…monetisable.

Jimmy and Crake are friends. In their youth, they experience together some of the worst facets of the digital world they inhabit, including violent and gruesome pornography and executions (hedsoff.com). They also play games such as Blood and Roses (pp89-92), a trading game in which players trade atrocities (blood) for human achievements (roses). This game is part of a wider gaming eco-system of Extinctathon monitored by Maddaddam. And it was from this game that Crake got his name which stuck (his real name was Glenn) from an extinct Australian bird. Jimmy’s codename was Thickney from an Australian double-jointed bird that inhabited cemeteries.

Oryx from the title is rescued from child sex slavery and becomes an intimate companion of both characters. Crake, we discover, is the evil genius heading up RejoovenEsense, the ultimate in unregulated mega corporation designing the future. For example, in this world, there is:

“No more prostitution, no more sexual abuse of children, no haggling over the price, no pimps, no sex slaves. No more rape. The five of them will roister for hours, three of the men standing guard and doing the singing and shouting while the fourth one copulates, turn and turn about. Crake has equipped these women with ultra-strong vulvas – extra skin layers, extra muscles – so they sustain these marathons. It no longer matters who the father of the inevitable child will be, since there is no more property to inherit, no father-son loyalty required for war.” (pp194-5)

Jimmy and Crake have very different university experiences. Crake goes to the elite Watson-Crick Institute: “Once a student there and your future was assured. It was like going to Harvard had been, before it got drowned.” (emphasis added, p203). By contrast, Jimmy went to the down-at-heel Martha Graham Academy: “The Academy had been set up by a clutch of now-dead rich liberal bleeding hearts from Old New York as an Arts-and-Humanities college at some time in the last third of the 20th Century, with special emphasis on Performing Arts – acting, singing, dancing and so forth. To that had been added film-making in the 1980s and Video Arts after that.” (p219).

Where Crake after graduation gets access to mega corporations, Jimmy settles for working in advertising for a company called AnooYoo before being invited by Crake to join him to promote their big product, BlyssPluss: The aim was to produce a single pill that, at one and the same time would:

- protect the user against all known sexually transmitted diseases, fatal, inconvenient, or merely unsightly;

- provide unlimited supply of libido and sexual prowess, coupled with generalized sense of energy and well-being thus reducing the frustration and blocked testosterone that led to jealously and violence, and eliminating feelings of low self-worth;

- prolong youth.

What is not on the label is that prolonged use renders one infertile.

In parallel to this we learn of life after the event in which Jimmy, known now as Snowman, lives in the forest and oversees the security of the Crakers that Crake had entrusted to him with in the post-corporate world. This we discover is only possible because of Crake’s scientific intervention that protects him where others perish. Snowman’s life revolves around trying to find food for himself left behind in old settlements – the corporation compounds – amongst the bodies. But venturing further into the forest and towards these places is dangerous. the Pigoons are now feral and themselves hungry. Finishing off what is left of humanity for the sake of a meal would not bother them.

This book is only marginally about climate change. We know it is hot. And we know that perhaps the East Coast USA flooded due to rising sea levels. We know that corporations and their technologies determine the future. And these corporations are in the hands of people for whom profit and power are central to their thinking. They and the corporations they lead are not founded on an overtly ethical platform. Business is simply business. That said, in true Bond villain style, there is more to it. The power to create life forms is balanced by the power to destroy lifeforms, too. Human, in particular.

Critique

On the face of it this is a straightforward dystopia novel. The world is controlled by corporations seeking to refine humanity to secure profit – through idealized/designer babies, disease control/vaccines/organs, human reproduction, etc. There is no real government or regulation. Something catastrophic happens by accident or design. There is no way back. In this case there is a relative peace because there are few other survivors. In many other dystopian novels, civilization breaks down leading to savagery in pursuit of resources.

The parallel stories work well. Atwood does not expect us to understand fully what is going on until quite late – probably at the point at which the two stories converge. The dystopia is plausible now, in 2026, though perhaps not so much in 2003 when it was first published. Though it is not the first dystopia novel. On that basis, it is not very revealing. Maybe it has not aged very well, or maybe it lacks something to say in a way in which 1985’s The Handmaid’s Tale perhaps does.

The friendship between Crake and Jimmy is explored at length. I have to say whilst Crake and Jimmy explore pornography in their bedrooms I, with my childhood friend, marvelled at coloured vinyl records and Matchbox die cast models (two things that we both collected). I will give Atwood credit here; she understands boys and men as well as any male author understands women and girls. I felt the bond between them. It leads neatly to the conclusion. Crake needed someone whom he could trust to protect his legacy in the event of catastrophe (which seems about 90 per cent certain it was planned rather than accidental).

More interestingly is the subtle surveillance state. There is resistance to the corporations with sporadic violence and internment. If I read it correctly, the Maddaddam movement is the focus of the resistance. Both of the main characters are being monitored and controlled arising from their family involvement in the corporations. Jimmy, for example, is often questioned by the pervasive CorpSeCorps armed security forces. They remind him to stay compliant, not least when they show him a video of the execution of his mother, convicted of treason, having rebelled against the corporation and paid the ultimate price (p302). Though in the video her words were clear: “Goodbye. Remember Killer [Jimmy’s pet rakunk]. I love you. Don’t let me down.” (p303).

Once again, then, Atwood is on top of the surveillance state. Something that is now normalized in China and now increasingly in the USA as the corporations take control of our data. The question for me is a simple one, did I need to read 430 pages of Margaret Atwood prose to reveal what is for me self-evident? The answer is, I think, “it depends”. For too long I have avoided fiction and I had forgotten how important it is for creating alternative worlds (the Sci-Fi genre) or at least taking us into the worlds of others who may have had very different life chances and experiences. More critical though is building narrative around relationships – this novel is particularly good in this respect. A number of years ago I was in a book group and we read quite a bit of women’s literature. Actually, that is the wrong term. It is literature that prioritizes the issues relating to women, primarily family and friends. As a younger man, I was quite dismissive of that literature and rebelled, when it was my turn to select a book by foisting on to others work by Will Self, for example. It is good to see here that Atwood can do men. There is only one female character in the book for a reason; namely, the cause of the event that sees off much of humanity is men. And my goodness, we can see that in the contemporary world where three old men in particular seem to engineering dystopia.

Picture: Margaret Atwood Photo by Piaras Ó Mídheach/Collision via Sportsfile

Book Review: Kim Stanley Robinson, The Ministry for the Future

People have different ways of coping with the climate crisis. Quite a few people just ignore it. Others deny it and actively seek to make it worse. Others expect someone or something else to fix it; surely there is a technological fix? I wake up each morning with the challenge in my head. What can I do more to change things?

A response has been to seek solace in art, theatre and music. Indeed, I have a playlist. Every visit to a gallery or exhibition is filtered through the climate lens. And now it is novels – not a medium that I have indulged much. I was never a great reader of novels as a child. When I grew up I immersed myself in non-fiction and newspapers. There is a point to my sudden interest. I have an objective. But first I have to read what are seen as the significant books of fiction that deal with the climate crisis. I also have to learn how to critique literature. This is not a skill that I currently possess. Please bear that in mind when reading. Also note, there are countless spoilers in this text.

My first book to review is Kim Stanley Robinson’s, The Ministry for the Future. It is an epic. The paperback has a small font and has 563 pages. There are two main characters. There is a lot of implicit violence. It is also a book unusual in explaining economic and innovation concepts; for example, discounted cash flow (p 131); the Jevons Paradox (p 165); Gini Coefficient/equality measures (p73); MMT (Ch73); Bretton Woods (Ch50) and the International criminal court (Ch56), etc. There are also free lessons in glaciology and geoengineering amongst other scientific concepts.

The first of the book’s two main characters, Frank May, is an aid worker in Uttar Pradesh. It is 6am and the temperature is already 38 degrees and the humidity 35 per cent. We know that heat and humidity are a lethal combination. And so it proved. When the power failed all life-saving air conditioning shut off. During the course of the next few hours 2 million people died. What we learn from this is that 2 million people is the trigger for action. No state can sit back when 2 million of its citizens die from what is not a natural disaster.

The Indian Government’s near first response was to execute a programme of geoengineering – depositing particulates into the upper atmosphere to deflect the sun and cool the surface. This contravened the Paris Agreement of 2015. No state should unilaterally undertake a programme of geoengineering where the impacts are unknown and cross-border. But they did it.

Frank May improbably survives, but his whole life is haunted by the experience. His post traumatic stress disorder impacts on those around him. His focus is on bringing about change by whatever means. He makes contact with an organisation called The Children of Kali, a direct action grouping that targets the world’s climate villains; namely, those who caused climate change and those who perpetuate it. The bosses of oil companies require 24 hour protection. The owners of private jets do not sleep easy. Diesel ships and aeroplanes will sink or crash on the so-called “accident day”. That, at least, sees an end to mass aviation.

Rejected by the Children of Kali, Frank kidnaps the book’s second main character, Mary Murphy, the head of the recently established UN entity, The Ministry for the Future based in Zurich. He is not very good at kidnapping since he allows the kidnapping to take place in her own apartment, one which is monitored by the local police, she being a target – by the right for threatening their profits or the left for not doing enough to threaten their profits. Before the arrival of the police, Frank confronts her with the “left” position. The Ministry is not doing enough to change things. It is incremental, transparent and easily captured. He tells her about the Children of Kali and the kind of action needed to bring about real change.

On the arrival of the police, Frank disappears through a back window and goes underground until he is eventually apprehended by the police after defending migrants from an attack by local fascists – naturally, immigration is a real flashpoint, and immigrants very much a target. Frank is sent to prison for the kidnapping and his involvement in the death of a man on the beach whom he hit with a large piece of wood.

Scary though the the kidnap experience was, Mary knew that Frank was right. She discussed with her Chief of Staff, Badim Bahadur, whether the Ministry had any black ops, not dissimilar to the Children of Kali. He was not about to disclose any activities of the sort, but the very reticence suggested that the Ministry had such an arm. This, of course, leads to questions about who is responsible for what? Is the Ministry sinking ships or the Children of Kali, or some other radical outfit with little faith in mainstream politics?

A core vehicle for change is the carbon coin. It is discussed extensively in the book. It has key features; for example it has to be supported by central banks, is securitised by the creation of long-term bonds, it is rendered by blockchain technology. It works whereby: “Every ton [sic] of carbon not burned, or sequestered in a way that would be certified to be real for an agreed-upon time, one century being typical…you are given a carbon coin…the central banks would guarantee it at a certain minimum price, they would support a floor so it couldn’t crash. But also it could rise above the floor as people get a sense of its value, in the usual way of currencies in the currency exchange markets.” (p174). It is a form of carbon quantitative easing. And it is a market-driven mechanism.

The carbon coin is based on a paper (actually a series of papers/essays) by Delton Chen (p172 – https://tinyurl.com/4c27dj9a) author of the key paper: Chen, D. B., van der Beek, J., & Cloud, J. (2017). Climate mitigation policy as a system solution: addressing the risk cost of carbon. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 7(3), 233–274. https://tinyurl.com/5ervkk74

The cover brands the “Ministry…” as “one of Barak Obama’s favourite books of the year”. We all know how important that endorsement has been in recent years. Whilst this may be good for sales, I am not sure if the scenario presented has the legs the author and Obama think and hope for. The first part of the book is apocalyptic, for sure. Lots of bad things happen to people; obviously the heatwave that starts the book results in mass death, but the terrorism/state-sponsored terrorism takes its toll, too. We do not ever get to know who did what. Curiously, the terrorism seems to go without investigation. We do find out who may be behind much of the terror, however; namely, brown people.

The second half of the book simply reassures. Yes, the climate crisis remains present, but the trajectory starts to go in the right direction. Global emissions are cut seriously, not least by the incentive provided by the carbon coin. The scientist innovate in ways that give hope. Though this part is difficult for lay readers like myself to judge relative to the carbon coin initiative (which has at least been subject to peer review). Some of the glacier adaptations do seem fanciful not just scientifically, but also geopolitically. Admittedly, the book was written before the second Trump administration and the current phase of the Ukraine conflict, but even before then, it would have seemed optimistic.

I suppose my biggest misgiving is Robinson’s belief/hope that already-occurring warming can be reversed. Tipping points are recognised, but they do seem to be glossed over. Migration is recognised, of course, but it is still a “problem” to be handled by efficient bureaucracy. There is, equally, not much thought given to food security, biodiversity and shifting global alliances. Without the security of world order, much of what is described in the second half of the book is unlikely to be feasible. And I have no confidence that that world order will be maintained. For example, I worry particularly about food security, centred as it is now around global value chains, limited genetic diversity of core foodstuffs such as grain, rice, bananas, etc. Interested readers should read Tim Lang. Hungry people do not play be the rules. And because of the trajectory, the second half of the book loses its momentum, suspense and mission. For the final few chapters I was waiting for something to happen. But it did not because the author had already determined that the world had been saved and that one of the main characters can actually retire and travel the world in an airship! The book, therefore, has a very long and unrewarding tail.

Anyone needing more – and there is more – should read clever review using an ideal-type approach to criticism, see the work of Solarpunk – Hacker. Worth a good few minutes of your time.

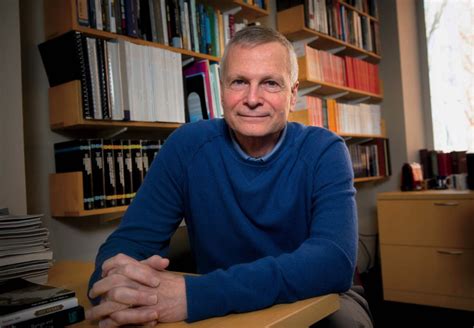

Book Review: Dani Rodrik, Shared Prosperity in a Fractured World

It was a good number of years ago a friend and former colleague of mine recommended the work of Dani Rodrik (left) to me. What I liked about his work was its humanity. He is a rare economist who recognises real-world challenges whist making the case for globalization and its impact on world poverty. That humanity stretches not only to responding to communications but granting me the rights to use some of his intellectual property in my own book at no cost.

So what was it that I thought was appropriate for my own book on Sustainable Business Strategy? Rodrick uses a simple but effective form of challenge: the Trilemma. On one corner is hyperglobalization, on another is national sovereignty and on the third is democratic politics. Democratic politics and national sovereignty are linked together by the Bretton Woods Compromise, an economic system designed to maximise domestic performance, essentially a Keynesian approach. Hyperglobalization and democratic politics are linked together by so-called global governance. Hyperglobalization is a concept that assumes that states are no longer the pre-eminent arbiter of world order. Economics is. States are subjugated to a system of global governance. Finally hyperglobalization and national sovereignty are linked together by the golden straitjacket; namely trade liberalization, free capital markets, free enterprise, etc. Readers will have noted that it is impossible for all three to co-exist. We can have two but not all three. Perhaps the world we live in today is the golden straitjacket with free reign for big tech and nationalism? We can talk about this later.

Rodrik’s Trilemma dates back to 2012 in his book, The Globalization Paradox, though it featured in his blog in 2007. Of course all of this was before the Paris Agreement (2015). It was business as usual. In 2025 it is anything but business as usual. Suffice to say, Rodrik has a new “tri” – this time a trifecta which is equally intriguing. This time at the apex is rebuilding the middle class. This is linked to global poverty reduction with the explanation that at its heart are growth-promoting policies in the North and South, without regard to carbon emissions (equating with Keynesian social democracy + export oriented industrialization). Rebuilding the middle class also links with addressing climate change; i.e. industrial policies and climate clubs among rich nations with discriminatory provisions or, in other words, Bidenomics. And addressing climate change is linked to global poverty reduction through the transfer of technology, jobs and financial resources from rich to poor nations; migration from South to North or, in short, Global Rawlsianism (after John Rawls’ principle that justice requires maximum attention to the needs of the least fortunate – p4).

The trifecta is not a trilemma as we can – and must – at least reconcile the three. And that is what this book is about. However, the paradigm is important here. Rodrik is not a revolutionary. He is very much grounded in a Keynesian/Rawlsian ontology. There is also a splash of technological determinism. By definition he is not a “no-growther”. But neither is he a hyper-globalizer or an economic neoliberal. Growth of sorts provides political stability, resources – financial, human and, indeed, natural. Rich states are mandated to share clean technologies with developing countries and exchange personnel. This is important because straightforward rapid industrialization in developing countries will just release ever more carbon; it is also the case that there are significant challenges and tensions in the trifecta. So Rodrik is a pragmatist, and all the better for that approach. Modern states and economies are so polarised at the moment, anything less than pragmatism leads us to extremes.

Key concepts

Productivism (p155) is another term for industrial policy. It is an industrial policy that can reconcile the trifecta. For example, a policy of carbon reduction through technology. Clearly carbon reduction helps in mitigating climate change by eliminating the main greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide. But it is also good for those other pillars, rebuilding the middle class (larger markets for other nations’ exports and investment as well as reducing outmigration) and poverty reduction (poor countries are disproportionately impacted by climate change – heat, sea-level rise, extreme weather and loss of biodiversity, amongst others). Productivism is, in the end, a shared policy mindset.

Experimental governance (p172) is borrowed from Chuck Sabel and coauthors (right). It is a form of governance that challenges key assumptions about policy implementation: (1) policy makers have clear objectives; (2) uncertainty is low; (3) there is little added value in policy makers communicating with private actors. Bearing in mind my own work on policy implementation, these assumptions do seem misguided. However, working with these assumptions, experimental governance has four elements: (1) goals are set between policy maker and stakeholders; (2) the executing agents are given broad discretion in how goals are achieved; (3) agents’ performances are subject to periodic review and results compared across different experiments; (4) objectives, metrics and procedures pertaining to the experiments are reviewed, revised and disseminated to a broader set of agents. It is iterative.

In academic research, this appears to conform broadly to an action research methodology. Over time, trust and capacity grow as the ideas and initiatives develop and mature.

Some examples

Notwithstanding much Chinese industrial policy featuring experimental governance, Rodrik illustrates the concept with two explicit examples. For the first, he takes us back to the execution of the 1987 Montreal Protocol – an international treaty – that effectively stopped further erosion of the ozone layer directly attributable to the release of CFCs from refrigeration equipment and enabled it to replenish. The scientists behind it – Crutzen, Molina and Rowland (right) were honoured 20 years after their ground breaking work that made the link between CFCs and ozone depletion. Regarding implementation, firms, supported by government agencies including the EPA in the USA, innovated, even if only to avoid regulation more generally.

For his second example, Rodrik draws on a the case of Fundacion Chile (p158) acquiring a small local aquaculture company which imported Norwegian and Japanese salmon farming technology and, in a process of “learning by doing”, developed an entire supply chain from feed to export logistics. The knowledge from this experiment was widely disseminated which literally spawned a salmon farming “rush” enabling exports to go from 300 to 24,000 tons per year in the 1990s.

Whilst both of these examples are illustrative of experimental governance, they both have had significant environmental impacts. Unfortunately we replaced ozone-depleting gases with greenhouse gases. Potent ones. And as for salmon farming, it is not only a huge polluter, but it threatens wild populations through disease and mutation.

OK, I found some weaknesses in two examples. That by no means negates the notion of experimental governance. Far from it. It only shows that experimental governance can be used for good or not-so-good purposes. And to be fair in the case of the Montreal Protocol the urgency meant that we did have to move quickly to find alternatives. Another measure taken was to ensure that refrigeration gases did not get released into the environment, CFCs or not. Salmon farming, however, was always going to be problematic. It is, simply, factory farming. Ultimately when humans put lots of animals together, especially if they are bred for size, disease will follow and, in the case of fish farming, escapes will occur. Factory farms also undermine the effectiveness of antibiotics, one of humanity’s greatest discoveries, now threatened by greed and excessive protein diets.

Three buckets

As a pragmatist and economist of trade, Rodrik offers us four “buckets” in which to put policy options as they relate to globalization (having accepted that hyperglobalization is neither possible nor desirable). Sovereignty will – and perhaps should – always trump international homogenisation.

1

Here we place policies that are “prohibited”; namely those that cannot be part of a viable trading order. Note here that prohibition does not mean that they will not happen. An example would be violating sovereign territory. Sovereign territory is all-too-often violated. More contestable example are policies that are what Rodrik calls, Beggar-thy-neighbor [sic] (BTN), by which he means policies that generate economic benefits made possible by the harm they generate to other nations. Much of the second Trump Administration’s thinking on trade fits here. But more generally here we can place currency devaluations and export subsidies explicitly designed to improve the terms of trade domestically at the expense of other nations.

2

This bucket contains policies that may be amenable to mutual negotiations and adjustments. They may benefit the country enacting them, but the benefits are more widely spread such as potential spill-overs. The mutual benefit part was the basis of WTO most favoured nation status for countries not directly engaged in the negotiations between two nations but achieve a benefit from adjacent bilateral agreements. Here we may also find protective tariffs (protecting nascent sectors or employees in those sectors). It may still generate monopoly rents, but they are incidental, not the purpose. Moreover, affected parties might be expected to respond, but only in proportionate terms and should be directly linked to the damage caused by the state imposing the affecting policy. Equally, export controls on technology destined for countries representing a security threat are not BTN, but they probably will impose economic costs on the importing country (at least until that country develops the technology itself such as may be the case with China and the USA). On this latter point, Rodrik seems agnostic. In summary, states can pursue policies in their own interests subject to them not being explicitly BTN and may be subject to wider negotiation between affected parties.

3

Here we find policies that essentially invite an open discussion about the policies being touted. These are discussions that might not ordinarily take place but can be – what I would call – de-escalatory. We work this out together. Fairly. It might fall out of this bucket if the originating state is unable to explain the purpose, even if it is not BTN.

4

This bucket is for policies that require the agreement of at least two or more states. These are multi-lateral policies where we will find many of the climate change-driven policies. These are negotiations over the health of the global commons, debt resolution and, of course, pandemics. The Montreal Protocol was a bucket 4 agreement.

Making sense of climate change-driven policies

If we start with green subsidies, which bucket? What about China that now has serious advantage in terms of manufacturing and market access. Surely, these subsidies constitute BTN? This requires some logical gymnastics. First, let us step back. Carbon pricing is way too lax. Current prices do not reflect the impact of carbon emissions on the environment and their warming effect. If that is correct – which it really is – then how might we balance the account? We might try to install with haste photovoltaic cells. With a very low price facilitated by subsidies from the Chinese Government, the panels are available in volume to do just that. That is a collective benefit caused by a green subsidy from a country that may have been designed to outprice other countries. However, those countries could have responded with their own subsidies; On the whole they did but rather late and not proportionately (p201). Arguably there was insufficient subsidy overall, not enough rather than too much (as the neoliberals would argue). In the end, subsidies from the Chinese State provided an affordable resource that could compensate for inefficient carbon pricing (and hence emissions reductions, bucket 3). We’ll take that. Bucket 2. I sense it could be bucket 3 if there was an amicability about it, but I am not sure. Suffice to say, Europe has also tried to protect its EV manufacturers against Chinese imports with tariffs. But there is something about the superior technologies being offered by Chinese manufacturers and cost which add to the complexity and the attractiveness of the Chinese product(s).

What about the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) introduced by the EU (January 2026)? The EU imposes upon its manufacturers auditing of carbon emissions attributable to the product. Any imports that exceed the maximum allowed have to be paid for with a tariff reflecting the additional carbon emitted in manufacture outside of the EU (defined by the probably inadequate carbon price set under the ETS). It is, of course, a policy designed to change the behaviour of actors external to the EU.

The EU has engaged in this type of trade policy for a long time. It is not just about carbon. Food standards may be captured here. Medicines, toxic materials, exhaust emissions, etc. Is it acceptable? Surely the first job of a (supranational)state is to protect its citizens and if there is evidence that a product is dangerous or deleterious to wellbeing collectively defined, then blocking or controlling it is surely the right thing to do. With CBAM, the EU is trying to protect its citizens against the impacts of a warming planet. In doing so, there is a positive spillover as the atmosphere is a global common. Surely that is defendable? Bucket 2, surely. Or bucket 4 – multi-lateral, if only within the borders of the EU. Moreover, the British responded with its own CBAM (futile really, but proportionate).

What about not trading at all with countries that violate environmental treaties – or indeed those that block treaty ratification? Well, seemingly that is bucket 1. I trust that doing so is against WTO rules – but what are they worth in 2025? Rodrik takes an interesting position with regard to trying to impose barriers against states that have poor worker and human rights records; for example, China’s treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Seemingly not in bucket 1 – so, it is allowable. Individual trade agreements could incorporate human/worker rights into the text. Presumably, also, the rights of indigenous people and, by association, the natural environment? And not to forget that the human/worker rights are part of the membership qualification for the EU. But they are hardly definitive and some member states are very much in violation as they progressively dismantle their liberal democratic structures and associated rights. There is no qualification needed for environmental protections, it seems. There could be, if agreed. But it seems very unlikely in the current incarnation of the EU and its parliament. The bigger question though is whether it is something that we must contemplate if we are to mitigate warming and adapt? Maybe the EU as a block could and should?

And one final one. I am just reading Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel, The Ministry for the Future. I will review the book elsewhere, but after serious heatwave in India resulting in the deaths of 2 million people (graphically described in the first chapter), the Indian Government goes ahead with a unilateral policy of geoengineering against a UN agreement that no country would go it alone because the impacts would be global, uncertain and temporary. In this case, geoengineering (depositing aerosols into the upper atmosphere to reflect heat) is in bucket 1. It’s a no-no. It is the violation of sovereign territory. There are many other examples. Damning of rivers has long been contentious and impacting downstream communities. Not to mention water pollution from human waste, fertiliser run-off and industrial processing. More recently, plastic beads (nurdles) and plastic waste more generally cross boarders. Apparel, equally, is exported and often dumped; for example in the Atacama Desert in Chile (right).

Summary

So, where does this take us? Arguably it leaves economists in charge for the time being. However, growing extreme right-wing/fascist blocs supported by the centre-right (as in the case of the EU Parliament and reporting rules under the CSRD) are rolling back efforts to mitigate climate change. To address the challenge something is going to have to give.

Pictures: Dani Rodrik from Harvard Magazine: https://tinyurl.com/5e4d22s9

Capitalism is the problem

I have been reading some excellent books recently. You know the ones that you wish you had written? I have written a book, and I have just read The Physics of Capitalism by Erald Kolasi. It is brilliant and takes no prisoners. It also a book that I will need to incorporate into the next edition of my textbook if the publisher ever gets round to inviting an update. I know my book needs revision, not least because we’ve all been on generative AI catch-up. My bio needs an update, too.

Back to Kolasi. He’s a physicist. A physicist taking on economists in a way that economists should have been taking on economics in the 21st Century. Back to me. My book starts with a statement about the finite planet and argues that business strategy has to be devised and executed so as not to breach the planetary boundaries, of which there are nine. Kolasi’s genius (at least for me) is to use his knowledge of physics to critique arguments by economists (and others to be fair) about technological “solutions” in the context of climate change. It is hugely effective and it tells it bluntly and with humour (though totally unfunny if you are an economist).

At its bluntest, Kolasi likens economists to people who simply cannot accept that we cannot make light go faster than the speed of light (3×108 m/s) or go below absolute zero (currently -273.15oC). More realistically, in terms of the efficiency of the stuff we use and rely on, internal combustion engines struggle to be more efficient than 35 per cent (conversion of liquid fuel into kinetic energy/Carnot cycle). 70 per cent is a theoretical maximum, but such an engine is unlikely to be put into a car; photovoltaics, 15 per cent (though theoretically possible, but never achieved, 90 per cent). And so it goes. As Kolasi notes, too, even if we could get 90 per cent conversion of solar energy to electrical energy we would still struggle to meet demand for panels and electrical energy as they need an energy source to extract raw materials and manufacture. There are limits (that neo-classical economists will not accept).

GDP and decoupling

The likes of Hannah Ritchie have been making a strong case for decoupling as a sign that capitalism can survive a climate crisis. We can grow economies (as defined by GDP) and reduce carbon emissions simultaneously and absolutely. It’s a dangerous myth.

Some definitions first: relative decoupling is simple reduction in carbon emissions whilst experiencing an increase in GDP. Absolute decoupling is a kind of safe zone where decline in carbon emissions outstrip growth and head towards zero. From what I can see, and have read, there is no absolute decoupling even using current measures of GDP. For Kolasi, the current measure is the problem as it does accurately measure change in the biophysical scale; namely, the use of natural resources in production and reproduction.

Then there is the question of permanence, assuming GDP is a fair measure of output. Kolasi tells us that with this perspective, economic growth and life expectancy have decoupled as Americans die earlier than previously. Where we thought there was a positive relationship between growth and life expectancy, that seems not to be the case. But no one is saying there has been a decoupling.

Then we can consider the data on emissions. They are to some extent estimates. We might have a handle on carbon dioxide, but we certainly do not have measures of methane, nitrous oxide, synthetic and fluorinated gases, all of which are more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide. Even before the Trump administration, the Environmental Protection Agency in the USA relied on self reporting by corporations! Now it is unlikely that any degree of self-reporting will be needed.

Finance

Talking of changes in direction, up to 2021, banks had been reducing (not eliminating) lending for fossil-fuel projects. That has now changed. The Guardian newspaper has reported that “Two-thirds of the world’s largest 65 banks increased their fossil fuel financing by $162bn from 2023 to 2024.” The US Treasury has withdrawn from the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, essentially giving a green light to private banks to start lending again. Indeed, JP Morgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs all withdrew from the net zero banking alliance. Here is a table of the worst offenders (apologies for the poor resolution, but if you download it, it is fine):

Be rest assured, banks have not changed.

The steam engine

A book that opened my eyes to the non-inevitability of industrial fossil economies was Andreas Malm’s, Fossil Capital. The argument was threefold: first, capitalists were not prepared to share resources such as flowing water. Second, flowing water was located in areas that required investment by capitalists in infrastructure such as housing, schools, medical. Thirdly, where this infrastructure existed, labour militancy was difficult to manage – wages were going down and work rates increasing. Capital is best optimised if it is mobile. The steam engine enabled capital mobility despite being less efficient than water, at least until major improvements were made to the design of steam engines (to stop them from exploding if nothing else). All this being true, it is not the whole story. Kolasi has helped me to refine this argument.

Let us compare changes over time (Kolasi 2025: 290):

| Year | Steam HP | Water HP | Wind HP |

| 1800 | 35,000 | 120000 | 15000 |

| 1830 | 160,000 | 160,000 | 20,000 |

| 1870 | 2,060,000 | 230,000 | 10,000 |

That brings us to two additional concepts that I did not get from Malm: exergy and spectralization. Exergy is a thermodynamic system’s maximum capacity for useful work (p290); spectralization is the “diversification and variation in the conversional methods of existing technologies in response to changing social and ecological conditions” (p222). And so…

“…Boosting the spectralization of conversional technologies was the main causal vector for the corresponding improvement in the efficiency of industrial devices. The Industrial Revolution in England and virtually everywhere else as well, followed a path of exergy-driven efficiency gains that spurred additional gains and butterfly effects in economic productivity. The English achieved this incredible growth through a huge increase in the aggregate output of mechanical work a process spearheaded by the spectralization of high-pressure steam engines, and eventually the spectralization of other types of engines as well.”

Kolasi, 2025: 290-1

Let me unpick that, probably imperfectly. Efficiency per se is not the point. It is exergy efficiency. And curiously, Kolasi demonstrates that steam engines had a negative impact on aggregate efficiency across the English economy as a whole. Indeed in their early days they were highly inefficient relative to water and wind. The more steam engines that were installed – at least until 1770 – the lower the efficiency of the economy in aggregate. My head hurts trying to get it around this idea.

In the 19th Century it is a different story. But steam’s impact is not that it could be used to power textile factories. Rather it is this spectralization whereby if became a significant component of the economy as a whole, not least in transportation (shifting coal to factories and shifting product to markets). And if we think that steam power is a thing of the past, we must remember that it is steam power that generates most of the world’s electricity.

Steam power does something else, too, which I had not considered. Steam enables capital to be used harder. By which we mean, it enables us to hit things harder – in a foundry, for example, that is useful.

That leaves a question as to why coal? Well here’s a thing, the answer lies is that great British phenomenon of the enclosures. Back in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the aristocracy displaced many people from their traditional lands by enclosing it – fencing it off and turning it into private property. This displacement led to a rapid urbanisation. People were concentrated in towns and cities and used wood to heat their homes. More rapacious, though, was the state’s need for timber for warships. The nation’s forests disappeared. Coal was a suitable substitute and, as Kolasi writes, “…the northern parts of England were full of it”. Full of it for sure, but it was under ground. The mines were established but they needed pumping. That was first significant industrial use of steam power – to pump mines.

The steam engines then went through spectralization – the addition of condensers to improve thermodynamic efficiency; new gear configurations that allowed the engines to generate rotary motion and to power machines in factories; and the transition from low- to high-pressure machines as the driving motive force. Kolasi (p281) argues this was the “breakthrough moment of the entire industrial revolution”.

Colonialism

The English enclosures displaced many and created a work-hungry proletariat. International colonialism resulted in mass slaughter, disease and slavery. Kolasi (pp300303) goes into great detail about the activities of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Most brutally, the company slaughtered the majority of the people of the Banda Islands (modern day Indonesia) because they had a monopoly in nutmeg growing. On discovering exactly where the fabled trees grew in 1621, 15,000 people lost their lives through brutal acts of beheading and being pushed over cliffs. These people were substituted for by slaves. The VOC set the stage for the Amsterdam Stock Exchange becoming the first publicly-traded company; but as is ever, the company declined as the secret of nutmeg was demystified and grown in other regions with suitable climates. The Dutch Government nationalised the assets in 1799.

The Circular Economy

We hear a lot about the circular economy…it is essentially another attempt at saving capitalism from itself. In its purist form, the waste from one cycle of production becomes the raw materials for the next. A weakness here is the issue of recycling. Many of us are asked to recycle our waste – my weekly doorstep collection is a case in point. I separate out my plastic, card, glass and metals to be collected. Notwithstanding the fact that turning glass and metals into reworked materials requires energy. Plastic…to much cannot be recycled, and even if it can, the capacity is rarely there to enable it. So, recycling is not realistically part of the circular economy – energy is lost in the circularity.

For circularity to be meaningful, materials have to be reusable or re-purposable. A glass bottle needs to be reused as a glass bottle (energy is required for transportation and cleaning. Textiles need to be re-tradable, up-cyclable and volumes need to come down, drastically. A recent story in the Guardian newspaper illustrates once again just how much textile materials find their way dumped in habitat and wilderness because we cannot absorb the volumes being disposed of.

Sources: Decoupling Chart – Hannah Ritchie (2021) – “Many countries have decoupled economic growth from CO2 emissions, even if we take offshored production into account” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/co2-gdp-decoupling’ [Online Resource]

Bank investment table – Banking on Climate Chaos: Fossil Fuel Finance Report, 2025: https://www.bankingonclimatechaos.org/?bank=JPMorgan%20Chase#fulldata-panel (accessed 21 June 2025)

Steam Engine: Chris Allen / Steam engine, Nortonthorpe Mills, Scissett

VOC Plaque: By Stephencdickson – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72939415

Ghana Wetlands – source unknown. Taken from Guardian story.

Ocean – David Attenborough

Thee weeks ago, along with my beloved and my sister I visited Bempton Cliffs in East Yorkshire. It is a colony of seabirds clinging to steep chalk cliffs. I took the photograph (left) of gannets, one of my favourite birds for their sheer seabird-iness! Many of the other people there were trying to see, quite rightly, some early-arrived puffins who normally breed at the top of the cliff in burrows.

In recent years, the colony has been deeply affected by bird flu. I was concerned that so devastated they may have been that the colony would not recover; but alas, they were there and as amazing as ever. Gliding, diving, hollering.

About the same time, we were trying to find a cinema that was showing Ocean featuring David Attenborough. You can count on one hand the number of people in the UK that have known a world without David Attenborough. It is also true that there is no-one alive who has not been witness – whether consciously or not – to the wholesale destruction of the world’s oceans. It is not about over-fishing. It is about the wanton destruction of marine eco-systems. Largely invisible marine eco-systems.

David Attenborough has come a long way. He started with a show that traced the capture of animals for incarceration in zoos, Zoo Quest, between 1954 and 1963. Of course he later fronted some of the most memorable natural history documentaries of the 20th Century. He worked with teams that constantly innovated film technique, sometimes encountering real risk in order to do so. However, in most of those films he did not – or was not allowed to – juxtapose the wonder with the destruction that was happening in parallel. In some cases they filmed simply metres away from organised and illegal logging in rain forests, and the destruction of many other habitats through pollution and resource exploitation.

This one-sided storytelling became increasingly intolerable for Attenborough. Habitat and species loss seeped into the films; but they were never central. It has taken a collaboration with National Geographic for him to tell the story that was not told in Blue Planet. And it is devastating.

My family has its origins in the fishing industry in my home town of Hull. They were trawlers – dragging a net along the ocean floor to pick up cod and haddock, fish that fed on the ocean floor. But that trawling literally destroyed everything in its wake. And 3/4 of the “catch” was discarded. Over and over again, these trawl nets destroyed eco-systems and emptied the seas. I – along with everyone else, probably – have never actually seen a trawl in action. Now you can in graphic detail. You can see the devastation. And you can understand why the oceans are dead or dying. Oh, and the process of trawling releases huge volumes of carbon dioxide locked into the seabed.

There is not an ocean anywhere not now being exploited by factory ships. In Antarctica, the ships have come for krill, a small crustacean that feeds penguins and whales amongst other to be processed into fish food (for all of that harmful salmon fish farming) and, wait for it, pet food. These are international waters being exploited by a select few corporations.

The film is in three parts. We start with the wonder of the oceans – in particular the bits we know the best (though seemingly only recently have we bothered to look), kelp forests and coral reefs in particular. Then the grim bit – probably 30 minutes of hell on Earth. And finally, the hope. There is hope. Kelp forests regenerate super quickly if left; so too, the fish species, even those thought to be lost. Coral can recover as some fish species remove the algae that effectively suffocate the coral and prevent regrowth. It is particularly salient at the minute because the film was released to coincide with the UN Ocean Conference (Nice, 9-13 June 2025). At that conference, the future of the oceans were being decided. You can read the communique here. on 15 June 2025, the Guardian newspaper published a summary. We need to protect 1/3 of the oceans the regenerate the rest. That is an amazing thought – just one-third can result in the rest of the Earth’s oceans recovering to once again provide a living for shore fisher communities globally. These communities have been subject to an ocean colonialism (Attenborough’s words).

Or we can turn the oceans into chronic deserts.

Why banks do not invest in renewables

I wrote last month on Andreas Malm and Wim Carton’s book, Overshoot. Like all arguments – and their book is full of them – there are weaknesses. Or in my case, a failure fully to understand. In pursuit of that understanding, I have turned to an extraordinary book by Brett Christophers, the Price is Wrong – Why capitalism won’t save the planet (right).

Christophers waits until chapter 6 – appropriately entitled, The Wild West, to broach the point of why. It is not because the previous chapters were superfluous – far from it. Rather it is because electricity is complex, and despite out belief that all electricity is the same, Christophers has to make the case that not all electricity is the same.

First, we have to look at the structure of the liberalised (i.e. non-vertically integrated markets), of which the UK is a prime example after privatisation in the 1980s. Let me break down some of the stakeholders in the system:

- Generators – owners of power plants (some located outside of the country)

- renewables

- wind

- solar

- hydro

- non-renewables

- gas

- coal

- biomass

- nuclear

- renewables

- Last-mile suppliers.

- Buyers of wholesale electricity for supply to end users (domestic and businesses)

- Electricity System Operators (ESOs)

Markets

Increasingly the industry’s liberalisation has led to regulated markets being constructed by policy makers. In the UK there two distinct routes to market by generators.

- spot markets (electricity for immediate use)

- corporate – Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) – generator contracts directly with corporate entity which is often a large user of electricity. There can also be PPAs between generators and utilities (retailers).

Spot markets trade in blocks of time, 30 minutes in the UK, for example. There is a base load, usually supplied by renewables and then a top-up, usually coming from the most flexible of supplies; namely, gas. In the UK the last coal-fired power station closed in September 2024.

Spot markets and volatility – why renewables are unattractive to investors and fossil-fuelled plant is attractive

The prices of electricity on spot markets are volatile. They are volatile over each day – demand can vary widely from the peak of the early evening to the overnight lull. But volitivity over a month…that seems to be more scary to investors. For example (p 170) in February 2022, spot market prices in Germany ranged from under €50 per MWh (day 19, Saturday) to just under €250 per MWh (day 25, Saturday). Demand is difficult to predict; indeed, we might ask, are there any other (commodity) markets with such pronounced volatility?

If you are an investor – a bank, for example – such volatility instils a sense of unease. It does not make investment impossible, but it makes it more expensive. Christophers’ research suggests that interest rates for renewable energy projects can be as much as 3x that of non-renewables.

We should then ask, why would a gas-fired power station – that sells into the same volatile market – not also be high risk? There are two things to be aware of here. First, banks have been investing successfully in fossil fuel projects for many years. Successfully. It is a known and tangible entity that has largely been low risk. Bankers, however, when making investment/loan decisions ask one simple question, will the client be able to pay back the loan on any terms agreed? The banker wants to know how much income the project will be generating to service the debt. The project owners will, of course, not be able to answer that question because of the volatility. It seems to be insufficiently adequate for the loanee to say that they are 100 per cent certain that all electricity they generate will be bought by suppliers because what they generate will always be cheaper than electricity generated by gas. The spot markets always include the lowest-priced electricity in a merit hierarchy.

There seems to be other issues here for investors. The returns on renewables is lower than that for fossil-fuelled plant. Typically, noted by Christophers (pp 211-221), fossil-based investments can generate returns of up to 20 per cent. Renewables come in at between 4 and 9 per cent. If we consider oil company shareholders, they are offered by the executive investments that will bring in double-digit returns, or equivalents that will deliver at best half of that. What will they choose? And what if the executive takes the decision to go with the renewables, knowing that their returns will be lower? Most will be out on the ears at the next shareholders’ meeting. These are so-called opportunity costs. Investing in renewables means that the investment will not be made elsewhere; i.e. something that brings in a higher return. But, argues Christophers, the shareholder concerns are minimal in comparison to that of the banks. Banks are looking for double-digit returns. It is also the case that many investments in renewables are made by companies that are not fossil-fuel based. They specialise in renewables. They will only deliver across their portfolio single digit returns to a market that is volatile, that exhibits the so-called merchant risk. Added to that, renewable plant is part of a “transition” – an energy transition. That transition, argues Christophers, has two elements. The first adds to the uncertainty. Transitions by definition are uncertain. The second is transition has no history. Generators are asked to project into the future with no historical data on which to make the calculations.

We might then ask, what about owners of plant fired by fossil fuels, how do they make the case to investors if they sell into the same volatile electricity market (because new gas-fired power stations are still being built)? Well, it seems quite simple, a traditional fossil-fuelled power plant is not part of a transition. It is proven technology and can demonstrate historical returns on investment. It is eminently bankable.

And here is another scenario. If the spot price of electricity (say in the UK) falls, so does the price of gas. The spot price is determined by the gas price (or the highest bid price in the bidding round, usually 30 or 60 minutes in each 24 hour period). In that scenario, the price of gas falls and the bid posted for electricity generated by a gas-fired power station is at a lower price because the primary cost of the power station is its fuel. If the gas price falls, so does the cost base of the plant. There is a hedge at work in the eyes of the bankers (p180).

The same is not true of wind-based renewables plant. The fuel – wind – is a gift of nature. It is free. The cost base of the plant, in the event of the spot price decreasing, does not decrease. That seems to indicate to bankers that there is a point where there is no return, and hence the ability of the plant owner to service the debt. In other words, finance cannot be secured because the fuel is renewable, meaning that even if the turbine is turned by the wind it can still be used by another wind turbine. But non-renewables once used are used. It is counter-intuitive that this is a positive and hence a challenge to bankers. In essence, then, there is a significant merchant risk; namely, “the risk associated with selling renewably generated electricity exclusively or predominantly at volatile merchant (wholesale) prices.” p174

Work arounds – how renewable plant owners can hedge the risk

Christophers offers three ways around this problem.

- Option 1: the futures contract. This is a situation whereby the electricity will be bought and sold at a predetermined price. The fear/danger is that the spot price falls such that revenue is flat and threatens not to cover liabilities. This is a balancing act where an option to sell (short) on the electricity futures contracts means that if the spot price does fall, the negative outcomes in terms of income “earned” in the spot market are compensated for by a gain in the futures market. Essentially, the trading value of the contract enables the sale to be transacted at a fixed future price which typically rises as the spot price declines. This is a common mechanism for hedging in liberalised electricity markets.

- Option 2 – swaps. These are more common in North America and Texas in particular. Swaps act as substitutes for futures contracts. The principle is that a party averse to risk relating to falling electricity prices can offset the risk by entering into a swap that pays out even if electricity prices fall.

Hedging, though, is complex. Only the largest producers have the so-called competence to hedge at scale. There are at the very least significant cash flow challenges. For example, if the spot market does decline, one party has to put up considerable cash to cover the decline. There is even a bigger challenge to contemplate. Christophers asks fairly, what happens if the renewable electricity supplier cannot supply the amount of power it is contracted to supply to the futures or swap markets? The above relate to Christophers’ arguments on pages 178-183.

- Option 3 – PPAs – these reassure banks that there will be a return sufficient for loan repayments.

- Option 4 – government subsidy/support. Such support has its own hazards.

- investment grants do not help in pricing

- Investment Tax Credits can help reduce the level of break-even spot price

- Price controls/Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs) – compensating generators when the spot market “reference” price drops below the contract “strike” price; though when the strike price climbs above the reference price, generators pay back into the pool. The net price is always the strike price.

Price controls stabilise markets and satisfy investors. But then introduces yet another source of uncertainty. Will governments – especially when they are fiscally stressed – honour or extend FiTs rates? Unless they do, renewable generators are back to spot price volatility. Christophers offers examples of state withdrawal in China and India (pp.

Notwithstanding problems with subsidies (option 4), markets can bankrupt renewables generators. In Texas in February 2021, a bolt of cold air caused a number of generators to cease as their equipment, not used to such extreme conditions, seized up. This was not just renewables generators. Fossil-fuel plant also seized up. As a result of the limited supply, electricity spot prises went up considerably. Renewables generators were supplying into a market with spot prices below $100 per MWh (as low as $50). During the crisis, prices were $9000 per MWh. Now if renewables generators were selling into that market, then there was money to be made (assuming the turbines were working, of which many were). But if the generators had PPAs at fixed prices, if they were unable to supply they had to go into the spot market to meet the terms of their PPA. That was enough to bankrupt generators (p310).

Why renewables will not supplant fossil fuel investments

Overshoot

For us non-economists there seems to be a logic that should prevail. If renewables are significantly cheaper than non-renewable fossil fuels, then why do banks and financial institutions continue to provide capital to the fossil fuel industry to extract more oil and gas, despite climate change?

For an answer, I return to the work of Andreas Malm and a recent book (2024), Overshoot (co-authored with Wim Carton). We experience overshoot when policy makers conclude that we can afford to spend our carbon budget in the (mistaken) belief that we can bring back 1.5 degrees by carbon capture and storage. Or even more problematically, reduce the surface temperature of the Earth through geoengineering. It is propagated by fossil-fuel industry lobbyists in order to maintain business-as-usual. Business-as-usual is important because sunk assets of the industry are long-lived and the value of the oil over which they have extraction rights is high.

Commodification

For Malm and Carton (pp209-218) an answer is the inability to commodify sun and wind. We can commodify the equipment that converts the sun’s energy into electricity. We can commodify wind turbines. But because the sun and the wind are renewable – i.e. tomorrow’s sunshine is independent of the sunshine from the previous day – it has not been used up. Moreover, using Marxist theory, Malm and Carton argue that value can only be ascribed to products if human labour is required in its exploitation. Even in the most efficient mining operations, humans are still directing the operation. Wind, sun and water are labourless. That makes them valueless in the eyes of economists. There is no “surplus value”.

By contrast fossil fuels are commodities. They are traded, stored and consumed. The sunshine cannot be traded. There is no world market. There is no OPEC equivalent in renewables. It has no economic value in the capitalist mindset. It is costless. But costlessness may be valuable to consumers, it really is not to capitalists because they are unable to maximise profit – or indeed generate profit at all. Consequently there is only so much renewable energy that any national energy system can support – Malm and Carton suggest about one-quarter to one-third. Above that, costless electricity is so abundant that the price drops to zero or below. It is in Marxist terms, a “labourless void”.

This phenomenon can be illustrated indirectly by asking, name and ascribe a capitalisation to the world’s biggest manufacturer of PV cells or wind turbines. Likewise the owners of the world’s largest PV farms. We can all name the top 10 oil majors and easily find a capitalisation. For those who think Tesla may be a candidate – notwithstanding the current crisis within the company – it is an automobile manufacturer, not a renewable energy company. Essentially, renewable energy technologies (of the flow) have “no talent for providing the accumulation of capital”. (Malm and Carton, 2024: 215).

Competition

Other explanations are available, of course. Is it that there is perfect competition in solar, wind, etc. Barrier to entry are not high and hence there are too many players in the industry (a very Porterian approach). As Malm and Carton argue, if that was the case, then the whole industrial revolution would not have happened as the textile industry was just that, highly competitive.

What is particularly interesting in these technologies is their disruptive potential that could be led by consumers. No amount of consumer demand for fossil-fuel-free electricity, as we have seen, will see off the producers of electricity from fossil fuels. The profit motive blocks this. But it is possible for consumers to become their own generators. And whilst the majority of citizens own little in the way of land, homeowners do have roofs – house, sheds, etc., And in those houses they have space for storage – batteries. Most consumers remain indifferent to this. Even better would be whole neighbourhoods pooling their roofs and generating electricity for collective consumption. The question here is just about the design of the delivery system. For the time being at least, the grid is optimised for national distribution, and as such does not accommodate collective consumption.

Why then has there been any investment in renewables. Malm and Carton offer five reasons.

- Government subsidies – paying someone to do it

- End consumers not needing to make a profit (whilst reducing their own bills)

- Early profit – first movers, for example

- Low rates of profit can still be justified up to a point

- Fossil fuel companies have invested in renewables to fuel their own plants because, like all end users, it is valuable to them

Ultimately market capitalism cannot deliver transition, a mixed economy can.

Michael O’Leary is right and very wrong, mischievously so

Michael O’Leary (left) is the boss of RyanAir. He has spent much of his life at the helm and took it from limping Irish airline to Europe’s biggest. As he says himself, RyanAir was early into the low cost business after the skies were deregulated and have kept the advantage over rivals. He’s fabulously wealthy off the back of that success.

So, on 26 December 2023 O’Leary proclaims that there is not enough used cooking oil in the world to fuel the world’s airlines for one day, let alone a year. on that he is right. But he has made many other claims that are not defendable with even a cursory analysis. Let’s take them one by one.

O’Leary argues that air travel contributes just 2pc of carbon dioxide. Ships contribute 5pc, but no-one is shouting about global supply chains. Here are 10 points to consider.

- We do not measure greenhouse gases as a percentage, we measure in absolute terms. That 2pc is equivalent to 800 Mt CO2 per year. If we are to get anywhere near even 2 degrees of warming (let alone 1.5 degrees), all GHGs have to be eliminated, Even a fraction of 1pc is too much. In meeting the 1.5 degree Celsius target, the atmosphere can absorb, calculated from the beginning of 2020, no more than 400 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2. Annual emissions of CO2 are estimated to be 42.2 Gt per year, the equivalent of 1,337 tonnes per second (https://www.mcc-berlin.net/en/research/co2-budget.html). At this rate, at the time of writing, we have 23 years before that budget is used up at current levels, but we have seen clearly how projections are changing – climate change is happening faster than expected. The models are being revised. And we continue to grow demand for fossil fuels whilst destroying carbon sinks such as oceans, forests, bogs, etc. For something most of us do not need, flying is disproportionately expensive in terms of carbon budgets.

- Whilst O’Leary might say that 2pc is not much, carbon emissions overall have doubled since the mid-1980s. Aviation has just kept up with the average increase in emissions across the board. Absolute emissions from aviation are increasing.

- Carbon generated by aeroplanes is not the same as that emitted by land-based activities. Indeed, if we consider aviation’s full impact it is more like 3.5pc. Aviation emits other greenhouse gases, and the release of water vapour at altitude significantly increases its warming impact. Accounting for this, its contribution increases by around 70%.

- CO2 emissions arising from aviation are not globally fair (equitable). It is the relatively rich who fly. 1 per cent emit half of GHG emission from aviation. Business class is more carbon intensive than economy. Private jets…let’s not go there. Most people on the planet have never flown (estimated between 80 to 90pc) and have not contributed to aviation-generated carbon emissions. Put another way, only 5pc of people fly in any one year (less than that for international travel). The average air traveller takes just over 5 flights per year (1).

- We do not adequately count all emissions. Domestic flights are ok – they are factored into national emission-counting, but international/long haul belong to no one (though airlines to count them). Incentives are not in place to reduce emissions from long-haul flights. This we must get to grips with, but recent stunts like those from Branson do not help.

- O’Leary seeks to distract attention – forget aviation, much better and easier to electrify cars and vehicles. Vehicular emissions are 20pc of the total with cars alone producing 3bn Mt CO2e annually. Another diversion – Air Traffic Control – if they could be more efficient there would be no need to spend hours circuling airports in stacks (the fact that there may be too many planes in the air is not considered).

- There is the technological fix – O’Leary has them all up his sleave. Seemingly he is “generally a believer that technology and human ingenuity will overcome climate change”. He goes on “I have no doubt that we will not decarbonise because we tax people more” So belief will get us there; though at this point in time, there are no viable electric planes in sight. Or any other fuels, for that matter.

- O’Leary argues that “[p]eople will absolutely not stop flying because of concerns about climate change”. This may, of course be true, but that is why we have Governments, regulations and tax to provide the incentives. What O’Leary is doing at RyanAir is expand capacity with the purchase of new fuel-efficienter aircraft. But they are not sustainable.

- So. let us look at the low cost base and the subsidies airlines get to maintain them. Fuel (tax) is a huge subsidy not open to land-based services. Some old data – but in 2012 the lack of tax on fuel amounted to an annual subsidy of £5.7bn. No VAT on tickets add 4bn to the total. In the UK, the Government actually reduced air passenger duty on domestic flights. Seemingly there is another £200m subsidy to the industry. And then there is the infrastructure provided by the state such as roads and rail links. Did Heathrow really need a fourth rail link to the airport with CrossRail?

- And on ships, there is a lot of discussion both amongst engineers, campaigners and industry about decarbonisation. Try these:

Pictures:

Michael O’Leary, World Travel & Tourism Council

RyanAir Boeing 737, By Dylaaann – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114958876

References:

(1) Stefan Gössling, Andreas Humpe, The global scale, distribution and growth of aviation: Implications for climate change, Global Environmental Change, Volume 65, 2020;

Book Review – Super Charge Me: Net Zero Faster by Eric Lonergan and Corinne Sawers

If you have a spare evening, buy this book and join the conversation between two wonderful dinner guests, Eric Lonergan and and Corinne Sawers. That said, I’m not sure that you’d get a word in edgeways, even if you wanted to. I suggest just listening and learning.

In the first instance, the format spooked me. It genuinely is written as a dialogue. The two conversationalists flesh out their arguments – they do not challenge one another, rather they develop one another’s points – or invite further development: “go on…” says Sawers, to avoid a cliff hanger. Unless one is paying absolute attention, it is not clear who is speaking, such is the mutual expertise revealed in the exchanges. The book can be read in one sitting.

This is not, be rest assured, one of those “I’ve read this so that you do not have to” reviews. I have been known to write these. Readers are invited into a conversation that needs full engagement (my copy has plenty of page markers for future reference, top left). In addition, if we are in luck, the shelf life of this book will be short. If we, our governments, and the global community more widely, make the transition, the book will have served its purpose and become a cherished museum exhibit.

I’ve reviewed some other books – Alice Bell’s wonderful, Our Biggest Experiment, for example – that reveal how we got to where we are. What we could have done; how we could have avoided the precipice that humanity has now perched itself upon. Those perspectives inevitably lead to despair and inaction. Lonergan and Sawers are future-oriented. There is little dwelling on the past. They discuss a bright future: one that is fair and safe. Readers do not even have to have that much knowledge about climate change because a couple of to-the-point sentences – to paraphrase Douglas Adams – “avoid all that mucking about in hyperspace” and gets readers up to speed. There is no time to waste. It is just better to start using the language of Super Charge Me straight away: appropriately-named EPICs (extreme positive incentives for change) and Mini Musks (those intractable problems – aviation and cement, for example).

What are EPICs? They are extreme because moderate does not change behaviour. They are positive because the behaviour change cuts carbon emissions. They incentivise (never think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives, says Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s long-standing business partner, p172). It is all about change. In particular, change that reduces carbon emissions.

But what are they in reality? I have been led astray, it seems. It has been known for me to advocate carbon taxes. My dirty vehicle is taxed – the vehicle licensing cost is high for that reason and it costs more for my on-street parking than for cleaner vehicles. But I still have it. The incentive to ditch is not sufficiently extreme. I’ve learnt recently, that keeping it is potentially better for the environment than buying a new electric vehicle, thanks to a recent BBC show, Sliced Bread. But this is the wrong thinking. I should not be replacing it, I should be using a substitute. I do not because there is no incentive provided by the relative price of that substitute. For example, to visit my family tomorrow using the train would cost me £153. Even with the high price of fuel, my dirty vehicle could do it for half that cost, and I could take two people and unlimited luggage (it is a van) with me. The substitute, if I read the authors right, needs the EPIC treatment by Government. It is their job to fix the relative price and provide the incentive to switch. More generally, it may need investment in infrastructure to do it (more trains/capacity), a change in work practices allowing slower and shared commutes or fewer and, ultimately, a change in the norms of behaviour – actually it is a bit passé to drive a dirty white van rather than take the train. What, no photovoltaics on your roof?! Etc.

These are obviously EPICs for individuals, but there are EPICs for states. EPICs are responsible for the collapse in the cost of solar/photovoltaics and wind power. My new favourites that are going straight into my curriculum are captured in the Green Bretton Woods and Green Trading Agreements. The institutions of the Bretton Woods post-war agreement include the IMF and the World Bank. In the context of the transition, Lonergan cheekily says that “I am not sure that the World Bank is up to the task” (p144), but credits the designers of the post-war economic system with bestowing upon the IMF a “magic power” that was apparently leveraged in the banking crisis of 2008 and more recently in the global response to Covid-19. This power is manifested in a “special drawing right” (SDR). Readers can discover the magic for themselves, but I would entirely concur with Lonergan that the designers of the Bretton Woods institutions covered all bases insightfully and provided utility well into the future.

Thanks also to the conversation, I now also know about Export Credit Agencies (they’d somehow passed me by). These agencies mitigate credit risk for banks lending to low-income countries. The authors argue that they can be repurposed towards carbon-reducing investments. They have served the fossil-fuel industry well in the past and can serve transition economies well, too, into the future.